The Arab Rising – Part I

The Arab Rising – Part I

WASHINGTON: Anger in the Middle East has exposed built-in contradictions in US policy towards the Middle East – a policy based on maintaining a balance between strong relations with authoritarian Arab states and democratic Israel and Turkey while advocating gradual reforms to promote human rights. In execution, the policy ended up supporting Israel’s military edge, political stability in Arab autocracies and fighting terrorists while overlooking oppression and corruption that weakened the friendly regimes. As the moment of decision arrives, the US risks alienating all sides.

For more stalwart allies like Egypt, the US went along with delayed transitions in power, over the decades, offering perfunctory objections to manipulated elections or plans for dictators’ children to resume reins. US diplomats recognized they were getting boxed into dangerous corners, as revealed by US State Department cables released by the WikiLeaks, but did not act. Delays in instituting strong reforms stoked pent-up anger and support for groups with more extreme positions – Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Syria, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and Salafi voices within coalition opposition groups like the Yemeni Congregation for Reform.

Occasional calls for reform from US presidents undoubtedly inspired some protesters in Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, Algeria, Sudan, Morocco and Yemen. About 5 kilometers from al Tahrir Square, packed with protesters and subject to low fly-bys of military jets, is Cairo University where President Barack Obama spoke to the Muslim world in June 2009, noting that the United States was “born out of revolution against an empire” and “respects the right of all peaceful and law-abiding voices to be heard around the world, even if we disagree with them.”

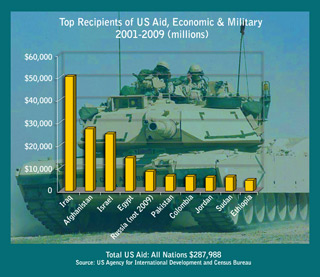

Past policies were untenable, as shown by the US tightrope walk between implementing Obama’s Cairo speech and demonstrators’ demands.The US position in the Middle East built on $1.5 billion in annual aid to Egypt, more than $2.5 billion for Israel and close cooperation with Saudi Arabia risks unraveling as Egyptians gather to demand the US ally Mubarak’s ouster.

The explosion of anger at Hosni Mubarak and son Gamal should not have surprised US diplomats. A September 2008 cable described “an Egyptian military in intellectual and social decline, whose officers have largely fallen out of society's elite ranks” and a tug of war over military support for Gamal’s succession: One professor contended that “the regime has tried to strengthen the economic elite close to Gamal at the expense of the military in an effort to weaken potential military opposition to Gamal's path to the presidency. Other analysts believe the regime is trying to co-opt the military through patronage into accepting Gamal.”

The military’s decision to allow peaceful protests could be due to many factors – passion of the overwhelming crowds, disgruntlement over corruption, concern over forgoing US aid by engaging in a violent crackdown or recognition of the inevitable need for change within the Mubarak family. The fact that the opposition Muslim Brotherhood favors some clean element of the army to oversee transition to democracy could also have played a role.

As protests raged throughout Egypt, opposition leader Mohamed ElBaradai urged the military to take “the side of the people” and not that of the tyrants. Addressing the international community, he echoed the siren call of Obama’s presidential campaign, promising that “Change is coming to Egypt.” He urged nations to review their foreign policies and revise accordingly, that stances taken during these early days could influence relationships with Egyptians for years to come.

A cable out of Riyadh foreshadowed ElBaradai’s prediction of coming changes for the Middle East: “Seen from the outside, the pace of political reform seems glacial,” notes the February 2010 cable. “Yet for certain elements of Saudi society, the changes are coming too fast. Whatever the pace, however, the reality is that serious reforms are gradually but irrevocably changing Saudi society.”

Other cables out of the Middle East foreshadow protesters’ complaints, including a worrying mix of nepotism and heavy reliance on the US, misuse of US military equipment and empty promises for eventual reform.

For example, leaders of Saudi Arabia viewed the United States as “its most important strategic partner and guarantor of its stability,” notes a February 2010 cable. With China poised to become the nation’s largest importer, with the US not acting swiftly enough on Iran’s nuclear development, Saudi Arabia’s “aging collective leadership” continues to develop ties with other emerging powers – China, Russia and India – to “counterbalance relations with the West.”

A cable from the embassy in Sanaa names a price for Yemen towing a US policy line: After President Ali Abdullah Saleh pledged unfettered access to Yemen’s national territory for U.S. counterterrorism operations, he noted, “I have given you an open door on terrorism, so I am not responsible”– for Al Qaeda attacks and possibly other consequences.

Israeli commentators lash out at the US, one suggesting that official statements “fuel the mob.” Yet Israel’s government recognized that such policies could not be sustained. “Israelis worry about the frayed nature of their relations with Egypt and are unsure about the outlook of the Egypt leadership that will follow Mubarak,” reads a May 2008 cable from Tel Aviv. “Israel enjoys excellent relations with the Jordanian royal palace and security services, but virtually no contact with Jordan's largely Palestinian civil society….”

By November 2009, another cable from Tel Aviv notes: “Painstakingly constructed relations with Israel's neighbors are also fraying. Even optimists about relations

with Egypt and Jordan admit that Israel enjoys peace with both regimes, but not with their people.”

As policy failures become apparent, divisions between democracy advocates and pragmatists who support stability for the region do not subside. A 3 January 2011 US Congressional Research Report on the Middle East summarized stances on using aid to influence Egypt: One group of analysts expected the Obama administration to improve the relationship by “de-emphasizing democracy assistance.” Others argued that traditional aid was ineffective and should instead target “daily lives of average Egyptians”; a third set argued for conditions tied to human-rights.

As events repeatedly show, aid does not shake stances that keep the powerful in their posts. Recent examples from the report: A generous US package of incentives for Israel bought only a three-month freeze in settlements, and the Egyptian government “staunchly opposed” aid directed to non-governmental organizations working on political reform, transparency or accountability.

Most of the top 10 recipients of US foreign military funds are in the Greater Middle East. Military aid is typically a fraction of overall aid – except in Egypt, where it’s five times greater than economic aid, evidently with Israel’s approval.[1]

Not that Israel and others didn’t raise concerns to US diplomats about arms transfers to neighboring nations, misuse of US equipment or regime change, as noted in the November 2009 Tel Aviv cable: “As it does in assessing all threats, Israel approaches potential U.S. arms sales from a ‘worst case scenario’ perspective in which current moderate Arab nations (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan) in the region could potentially fall victim to regime change and resume hostilities against Israel.”

Yemen’s Saleh responded to concerns that “economic and other assistance might be diverted through corrupt officials to other purposes,” according to a September 2009 cable, and “urged the U.S. to donate supplies and hardware rather than liquid funds in order to curb corruption's reach.” An embassy comment notes the suggestion “hardly provides a viable solution for stemming the curb of corruption in the long run.”

A new era emerges for nations enduring long years of authoritarian rule. Mass protests mark a turning point for the US in how it distributes aid and under what conditions.

US policymakers knew they treaded on thin ice. Whether from inertia or fear of instability, they stuck to the path, and now must maneuver as Tunis and Cairo explode in rage.

http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/RL33003.pdf