Chilean Rescue Offers Lesson in Globalization

Chilean Rescue Offers Lesson in Globalization

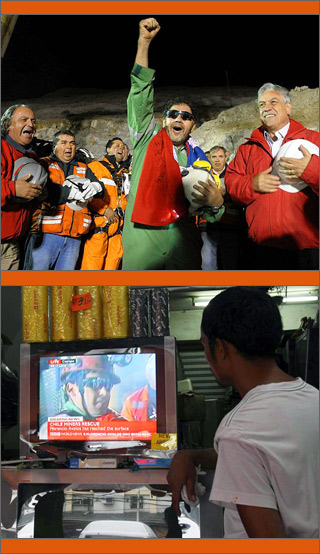

WASHINGTON: For 24 hours last week, the world was riveted on Chile. Major news channels – from BBC to CNN – suspended programming to follow the rescue of 33 miners trapped deep beneath the earth’s surface. Viewers around the world held a collective breath as the global media brought common focus to persistent problems for miners, invisible soldiers in a battle to extract minerals for a hungry world, and highlighted unprecedented international cooperation.

One mining publication called the high-profile rescue a “great triumph” for Chile and the global mining industry. While the rescue had a happy ending, it displayed a risk-averse global society that demands comforts at low costs, prioritizes profits over safety, and delays regulation while swiftly collaborating during crisis.

Neither consumers nor industries enjoy paying upfront for unplanned events, and this is true of the mining industry. The Chilean rescue, estimated to cost up to $20 million, could leave insurance firms and investors scratching their heads about the next unplanned event and inevitable comparisons. “The boards of companies, in particular those of global organisations, have become more concerned with ensuring that their management teams have robust and ‘fit-for-purpose’ risk management processes in place,” explains a 2008 Australian document on managing mining-industry risk.

Chile holds about 30 percent of the world’s copper reserves. China, with its own reserves, is the biggest user. Surging demand in Asia has brought near-record prices in global copper markets, enticing small mining firms to amp up operations to supply the metal for homes, vehicles, countless electronics.

While large Chilean mining firms have above-average safety records, small San Esteban operated its sole mine with high debt. After the collapse, the company admitted lacking resources to mount a rescue. In hours, the government turned to Codelco, the state-owed company that called on experts from around the globe. The waiting men stretched a two-day supply of food for two weeks as rescuers drilled a small hole and discovered August 22 the men were alive.

Adding to the atmosphere of a great sporting event, the Chilean government coordinated teams from South Africa, the US and Canada and approved drilling three man-sized holes – also relying on New Zealand sensors, Australian 3D mapping technology, Japanese video technology, and a global bounty of health, shipping and entertainment supplies. As drilling proceeded, Chile’s navy constructed the capsule used to lift the men from 700 meters below, relying on some of 75 designs sent by NASA and other government agencies.

The US team – including a US Schramm rig donated by a nearby UK mining firm and a custom drill bit from Center Rock, a US firm that specializes in opening large holes – broke through first, ahead of schedule. Center Rock’s CEO traveled to Chile to oversee the operation. Drill operator Jeff Hart was pulled from drilling military water wells in Afghanistan. California-based Oakley donated stylish sunglasses for the miners’ exit from the shaft.

Collaboration was on full display, both above ground and below, for the media gathering. No one miner took credit for restoring spirits; no single company took credit for the rescue operation – and perhaps that spurred media fervor. Front Row Analytics estimated that the Oakley donation alone, 35 sunglasses at $200, was worth $40 million in global television advertising.

Viewers around the world, however, had their own context for assessing the magnitude of scenes from Chile. In China, where mining accidents rarely make national headlines, media covered the rescue in detail, but avoided linking it with devastating domestic accidents and poor response. For example in March, managers of a coal mine in northern China ignored reports of leaks and a shaft flooded: 108 were rescued early, 115 more than a week later, leaving the rest trapped and presumed dead. Chinese bloggers though, did not hesitate to compare, bitterly complaining about China’s lack of safety precautions.

Eerily, hours after the last trapped worker emerged in Chile, an explosion in a central China coal mine killed 21 and trapped 16 – shifting international attention to dismal scenes of another rescue attempt, weeping families and China’s safety record. China had 2631 mining fatalities in 2009 compared to 35 in Chile and 34 in the US.

Tolerance to occupational, financial and environmental hazards varies wildly around the globe. As prices rise, firms explore at greater depths, small firms enter the market, inexperienced workers are hired, and dangerous mines are reopened. While the global financial crisis has slowed some risk appetite, according to a 2010 Ernst & Young report, responsible firms struggle to compete against irresponsible firms. Global investors remain wary of industry unknowns and potential for ruined reputations that devalue investments. Perceptions of danger could aggravate the industry’s severe skill shortage, leading to cross-border poaching. The report notes only 15 percent of mining engineering graduates in South Africa enter the industry. “Ours is an increasingly interdependent global economy and risks that can damage your business can arise in any market sector,” the report concludes.

Back in Chile, the world media glare had predictable consequences. Anticipating film deals, the men made a pact to share proceeds from the event. Global gifts of cash, iPods, trips to Greek islands and Elvis Presley’s home in Memphis, Tennessee, flow to the men. The outpouring of donations to a select group perhaps assuages guilt over society’s refusal to pay higher costs for regulations on safety. In truth, risk-averse societies prefer fairy tales and denial to realistic statistics on risk or tales of grueling work routines or long-term safety planning. Some industries progress by promising the worst cannot happen.

The Chilean rescue depended on donated time and equipment, and there’s no guarantee of good will emerging for future rescues. The government announced closure of the San Jose Mine; options for the mine include storing mining waste or renting shafts to financially secure firms. Rumors persist in Chilean media that multiple drill holes and advanced technology exposed new gold veins in the mine, reports the Santiago Times.

One rescued miner, Edison Pena, admitted anger to Al Jazeera. “Why do these things have to happen… because the employer to make money tells the worker ‘just go on in.’ The mountain is making noises but no… ‘go on in, go on in.’”

Mining project risks must be considered over the long term, suggests the Australian document on risk. Failure to do so imposes extra costs for individual operations or the global industry as a whole. The document urges Australia’s mining industry to abide by the precautionary principle, as stated in the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, in protecting against environmental harm or threats to human, animal or plant life: “lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures.”

New regulations could cost billions, and the Chilean government promises an investigation, while doubling the number of inspectors and closing 20 other small mines. The nation’s regulatory agency had 18 inspectors for several hundred mines.

Disaster prevention can never be as thrilling as triumphing over crisis. Steady prevention, solid safety records, capture few headlines, movie deals or speaking invites.

With the internet, global statistics on production and safety records for industries and mines are at the fingertips of workers, investors and consumers. Risk is inevitable, but intentions do matter. Those who knowingly take on the consequences of risk are heroes. Shifting the consequences to the poor or future generations is unconscionable.