Global Causes Attract Growing Share of US Giving

Global Causes Attract Growing Share of US Giving

WASHINGTON: After the 2008 financial crisis, economic growth took a tumble, and amid anemic indicators since, charitable giving would be expected to decline. Indeed, after the global recession, giving dipped in the United States. Yet US giving to charities international in scope rose an estimated 15.3 percent in 2010 – the largest percentage increase of all categories, including religion, health or education.

Global giving is an emerging trend, as the internet and social media raise awareness of global needs, reports Giving USA Foundation. Individuals seek global recognition, and companies make strategic moves in emerging markets that provide a lion’s share of revenues. The trend also reveals America’s individualistic streak and near reverence for high-profile donors like former President Bill Clinton or Microsoft mogul Bill Gates who identify and solve problems.

Take Gates for example: The 2010 annual report of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation explains that nearly 80 percent of grants were directed to global development and global health, while 15 percent went to US education, libraries and other programs and 4 percent to non-program grants. Of course, contributions for vaccinations, education or stability ultimately benefit all. Likewise, more than 70 percent of 2010 expenses of the William J. Clinton Foundation were directed toward global initiatives.

Such giving runs counter to isolationist trends in the United States, including opposition to foreign aid, support for anti-immigrant legislation, weariness over wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and fears about outsourcing and ballooning national debt.

Exuberance for giving as opposed to paying taxes reveals deepening mistrust about government’s ability to manage funds and distribute benefits fairly. Instead, donors seek direct control over how their money is used, selecting among recipients who pull heart strings with compelling appeals.

Motivations differ for households and corporations. Research suggests that corporations aim for brand enhancement, new markets and shareholder interests. International giving goes hand in hand with international sales. Topping the list of most generous companies with cash donations, compiled by Forbes magazine and the Chronicle of Philanthropy, is Walmart followed by Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo. The three corporations gave $319 million, $315 million and $219 million, respectively.

Annual reports offer rationales for a global presence. “[O]ur international segment continued to be a growth engine last year – generating a 12 percent net sales increase,” explains Walmart’s 2011 annual report, which points out the international market represents half its overall units and 25 percent sales. “Our international leadership teams are accelerating organic growth in emerging markets, including Brazil, China, India and Mexico.”

About 7 percent of Walmart’s giving was directed to international causes, like the Global Women’s Economic Empowerment. And even as US politicians shun issues like climate change, major US corporations like Walmart demonstrate leadership on international trends like sustainability and reduction of carbon emissions.

The BRICs and other growth economies are “anchors for the global economy,” suggests the 2010 Goldman Sachs annual report. “As tumultuous and significant as the financial crisis was, we continue to believe that this will be the century of the BRICs and other growth markets.” About half Goldman Sachs revenues come from the Americas, the other half from Europe and Asia.

The third-ranking donor, Wells Fargo, is the least internationally oriented of the nation’s four largest banks, notes Dan Freed of The Street, but the company is “taking steps to ensure it won’t be left behind in the global business race.” Lending a hand are nonprofits like Global Impact, a matchmaker between international causes and corporate partners, and UpwardlyGlobal, which provides training and job referrals for skilled immigrants.

Well Fargo’s 2010 annual report emphasizes community lending and assisting corporate customers with expansion in global markets, and its giving still focuses on US-based organizations. Goldman Sachs did not respond on its percentage of international giving, but in December announced a strategic partnership with Denmark to match entrepreneurs with affordable loan products, an extension of its five-year 10,000 Women initiative to provide business education to underserved female entrepreneurs in developing and emerging markets.

Overall, US charitable giving has steadily climbed, from less than $25 billion in 1970 to $290 billion in 2010, both in current dollars, reports Giving USA. Total nonprofit organizations exempt from taxes went from 865,096 in 2001 to 1.28 million in 2010.

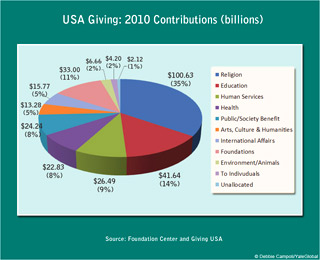

Corporate giving is miniscule compared to that from individuals. Of $290 billion contributed in 2010, individuals represented 73 percent; corporations and foundations represented about 20 percent. Troubles for the US economy reduced individual giving by about 1 percent between 2008 and 2010, while corporate giving increased by 23.2 percent. While the categories have overlaps, religious causes attracted 35 percent of funding; health and human services, 17 percent; and education, 14 percent.

Support for international affairs took a small share of the charity pie, attracting about 5 percent of all US contributions in 2010, more than $15 billion. By comparison, US foreign aid costs about $45 billion, about 1.5 percent of the US budget.

In 2005, Natalie Ambrose of the Council of Foundations predicted a rise in global giving, based on emergence and transfer of new wealth, global crises, and more connected global citizens. “Therefore, in this increasingly integrated, interdependent and rapidly changing world, it is foolhardy to consider or address problems as isolated targets,” suggested the council’s 2011 report Moving Beyond Boundaries: The Rise in International Giving. The report calls for data on motivations and consensus on priorities to improve efficiency. It also calls for increasing the social cachet of giving, quoting an analyst who suggested it should “be awkward and embarrassing to be seen as not generous and aggressively involved in social investment.”

Reports of corruption or mismanagement immediately chill giving: In June 2011, the Associated Press reported that as much as two thirds of grants donated to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria were lost in corruption; in July, the New York Times reported on a Red Cross Society of China executive boasting of a lavish lifestyle; and Forbes bounced charities off its list for donating deworming pills, worth 2 cents, and marking up their value by 50,000 percent on financial statements.

The US monitors its charities more than most nations, but accountability remains inconsistent, as demonstrated by the recent Penn State University debacle. Boards of directors decide on compensation packages, and a web of connections can lead to conflicts of interest. Executives of nonprofit health care systems, museums and universities can earn salaries well more than $1 million.

The US Budget Office estimates that the cost of allowing tax deductions for charitable organizations will be $315 billion from FY2011 to 2015.

Government institutions and media in emerging nations have a long way to go to catch up on monitoring salaries and administrative costs. The British Charities Aid Foundation encourages governments to name ministers to oversee civil society, demand standards of governance and oversight, encourage a norm of giving at least 1.5 percent, commission surveys on trends, ensure tax-effective mechanisms for cross-border giving and encourage finance institutions to assist charities.

Watchdog groups warn that governments could intervene if the sector fails to promote transparency, independent boards, audits or records retention that reduce conflicts of interest.

Without consistent global governance, the largest corporations and wealthiest individuals won’t lose influence. Rather, the US style of giving and resistance to tax-funded government programs could spread around the globe.