Art and the Global Economy

More people participate in the creative economy due to exponential global population growth and expanding middle classes in developing economies, and as with other sectors of the economy, globalization has transformed every aspect of the art industry, writes John Zarobell in his book Art and the Global Economy. The creative economy is more than just another subset of the global economy, and he argues that “art carries meanings beyond the price tag.” This is partly because art’s economic contributions are not easily quantified. Definitions of art puzzle artists, collectors and economists, and values are tentative, based on shifting whims and fashions. While a stray comment by a curator or celebrity can influence the market, the long-term value for artwork is linked to history, culture, political activism and social meaning as well as intricate connections among artists and purchasers, exhibitors and visitors, curators and donors.

Boundaries are eroding, and artists from around the world with unusual stories and talent increasingly penetrate the traditional art centers of London and New York. The industry is more decentralized and diverse with greater interest in contemporary and non-Western art. Contemporary art represents about 40 to 50 percent of all art whether based on volume or value, and most contemporary art comes from Asia and Africa rather than the United States and Europe. Collectors prowl for new talent even as many contemporary artists resist national identification and seek universal appeal. Any artist can cultivate global relationships, small institutions can initiate global dialogue, and small shows with new approaches can capture global attention. The book includes anecdotes of artists with limited funds who find creative ways to inspire their communities: A Palestinian artist devoted two years in organizing an exhibition of a single Picasso painting in the Occupied Territories. Small artist-run spaces in Moscow refuse to rely on oligarchs. Artists sell work in Central America's open markets, and artists in Cambodia, Vietnam and India pool resources to create collectives and artist-in-residence programs.

Production and consumption of art is on the rise, and distribution requires creativity. The industry embraces globalization, and global integration has hastened development of alternative networks for production and consumption, explains Zarobell. For new entrants, the industry offers little in the way of security, and so practitioners cooperate as much as they compete via art collectives, art fairs, biennials and other projects. Communities around the globe increasingly view museums, art fairs and art spaces as centerpieces for urban development, cultural districts and branding tools for attracting tourism and investment. “Cities in emerging economies are experiencing significant growth as a result of changes wrought by economic globalization, and they seek cultural institutions to burnish their status as global metropolises,” writes Zarobell.

While art is plentiful and contributes to vibrant cities, museums must compete for visitors and funds. Key funding models include public and state funding, nonprofits and private donor and corporate funding, though Zarobell points out that public support is dwindling despite increased visitor demand, popular exhibitions and expanding collections. Brief essays profile the aspirations of Delhi, Hong Kong, Moscow, Istanbul, Doha, Mexico City, Johannesburg and Rio de Janeiro as art centers with artist-run spaces, corporate sponsorships and private-public partnerships. Funding is uneven and variations are immense – in China, state planning launches high-profile building programs while Istanbul capitalizes on its historic neighborhoods. Under Brazil’s 1991 Rouanet Law, companies can support the arts in lieu of taxes as long as the activities are free for the public. Regardless of the strategy, cities ready to welcome and build an art community may be more adept at absorbing the effects of globalization.

The industry relies on the internet and digitalized photographs for market, yet art and its many forms of presentation and distribution thrive on the “experience economy” – cultural programs, workshops and entertainment designed for audiences who appreciate the participation and memories. Saffronart is an exception: A mix of wealth and nostalgia among the Indian diaspora may explain why the online auction house succeeds in offering South Asian art to a global clientele while a partnership between Sotheby’s and Amazon lasted less than a year.

Art also travels, and Zarobell describes the global behind-the-scene processes of international shipping, customs, insurance policies, tax-free “freeports” and other storage arrangements that support otherwise free-spirited events – a growing exhibition complex of biennials and art fairs. He identifies other trends tied to globalization: donor trusts that support the lending of art rather than giving it to one institution, prominent individual collections influencing the global market, huge blockbuster exhibitions promoted well in advance, expansion of galleries in pursuit of worldwide recognition, art associations hosting education alongside international exhibitions, and increasing distinctions among categories even as boundaries between commercial and fine art erode.

So much uncertainty over value and the increasing number of cross-border transactions contribute to speculation, money laundering, arbitrage, tax avoidance and fraudulent price-boosting called “stir-frying” by the Chinese. Curators and collectors wield power over the market, Zarobell notes, and art that lands in a museum immediately gains value, akin to “insider trading.” He concedes that “art is one of the most unregulated industries on the planet.”

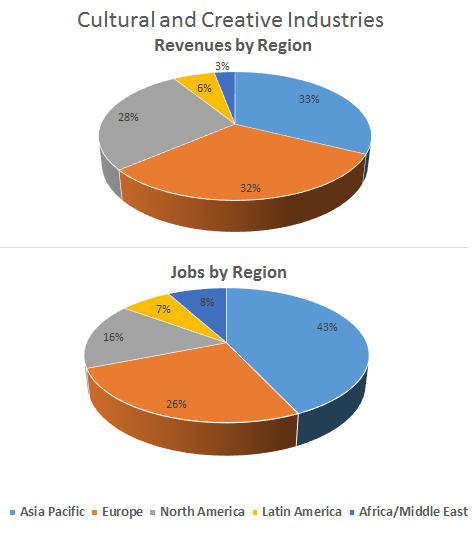

Art and artists contribute tangible value to their communities. A global report by Ernst & Young points out the cultural and creative economy, broadly defined, provides about 30 million jobs and generates $2.25 trillion annually. Such a large segment of the economy should not be taken for granted, and Zarobell wonders if neglectful communities could lose creative industries in a globalizing world the same way that they lost manufacturing. In discussing art’s entanglement with innovation, resistance and social critique as well as global markets and capitalism, Zarobell is circumspect yet hopeful: “It is not possible to escape our historical context or the capitalist system that has spread across the planet, but it is possible to read this social and economic realities against the grain and to find in them the means to transform our individual and collective existence. If anyone has a chance of re-forming our world, it is the artists and those who are inspired by them.”

Potential readers might wonder if this book might appeal more to artists or economists. Anyone who cares about art or their community will gain insights for riding the tides of economic globalization from anywhere in the world.

Susan Froetschel is the editor of YaleGlobal Online. She was previously a critic/editor with the Yale School of Art's Graphic Design Program and is the author of five novels including Allure of Deceit, set in Afghanistan.