The exponential growth in the exchange of goods, ideas, institutions and people that we see today is part of a long-term historical trend. Over the course of human history, the desire for something better and greater has motivated people to move themselves, their goods, and their ideas around the world.

Since the first appearance of the term in 1962 ‘globalization’ has gone from jargon to cliche. The Economist has called it “the most abused word of the 21st century.” Certainly no word in recent memory has meant so many different things to different people and has evoked as much emotion. Some see it as nirvana - a blessed state of universal peace and prosperity - while others condemn it as a new kind of chaos.

If properly defined and applied, the “g-word” actually does have some utility. It can best be understood as a leitmotif of human history. It is a trend that has intensified and accelerated in recent decades and come into full view with all its benefits and destructive power. Just as climate has shaped the environment over the millennia, the interaction among cultures and societies over tens of thousands of years has resulted in the increasing integration of what is becoming the global human community.

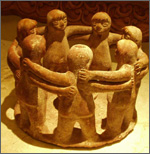

Globalization - defined by Webster’s dictionary as a process that renders various activities and aspirations “worldwide in scope or application” - has been underway for a long time. Thousands of years before the root word for this concept - ‘globe’ - came into use, our ancestors had already spread across the earth. In fact, the process by which they migrated and populated all the continents except Antarctica was a kind of proto-globalization. Some 50,000 years ago early forms of homo sapiens, who developed in east Africa, began to travel to the far corners of the world, including to the continents of North and South America. Rising sea levels at the end of the ice age separated the Americas from the Eurasian land mass, creating two worlds that were now cut off from each other. They would not be reconnected until Christopher Columbus’s serendipitous landing on a Caribbean island in 1492. That same year a German geographer, Martin Behaim, built the first known globe as a representation of the earth.

The reconnection was called the ‘Columbian exchange,’ and it is celebrated as a landmark in the history of globalization. The discovery of the New World brought together peoples who had been separated for over 10,000 years. No less significant has been the exchange of plants and animals. A Peruvian tuber, the potato, has become a staple throughout the world, Mexican chili pepper has taken over Asia, and an Ethiopian crop, coffee, found new homes from Brazil to Vietnam, to name just a few. In the intervening period, societies have not only evolved in radically different ways and developed different economic and political structures, but they have also invented different technologies, grown different crops and, most importantly, developed different languages and ways of thinking. That diversity makes the job of reconnecting civilizations both challenging and rewarding.

Historically there were four main motives that drove people to leave the sanctuary of their family and village: conquest (the desire to ensure security and extend political power), prosperity (the search for a better life), proselytizing (spreading the word of their God and converting others to their faith), and a more mundane but still powerful force -curiosity and wanderlust that seem basic to human nature. Therefore, the principal agents of globalization were soldiers (and sailors), traders, preachers and adventurers. Signs of trade in the dawn of civilization can be seen in old seashells carried deep into the interior of Africa. Thousands of years ago traders carried goods from one part of the globe to another across oceans. Missionaries traversed deserts and mountains and sailed the seas. The spread of Buddhism from India to Indonesia led to the creation of the Borobudur temple, which is one of the first monuments of globalization. From the Chinese Buddhist monk Faxian’s journey to India in the 4th century, to the Arab explorer Ibn Batuta’s travels to Europe, Asia and Africa a thousand years later, adventurers have continued to find new frontiers and establish connections among far-flung societies, cultures and economies. Even though travel was slow and dangerous, ambitious and acquisitive leaders - from Alexander the Great to Genghis Khan - ventured far from home and brought new lands under their sway. Conquest meant globalization in both directions, since the rulers often ended up being as influenced by those they ruled as vice versa.

The cast of characters whose drive and determination have established links of both domination and cooperation has changed with times. Small bands of traders carrying their wares on their backs or in boats have been replaced by giant enterprises, starting with the Dutch and British East India Companies in the 17th century. In place of solitary pilgrims and priests have come vast religious organizations that spread their beliefs, along with their languages, literatures and architecture. The few intrepid adventurers and travelers of past centuries who brought distant societies together have given way to thousands and even millions of refugees and immigrants fleeing across borders, as well as hundreds of millions of tourists jetting around the world. All these comings and goings deepen and broaden the connections among far parts of the world and facilitate the transmission of goods, ideas and cultures.

The commercial history of the past five hundred years is marked by other trends and transactions that have strengthened the bonds of interconnectedness. The rubber plants uprooted from the jungles of Brazil and transplanted in Malaysia by British colonialists in the first years of the 20th century provided the raw material for the tires in Henry Ford’s Model T; the indentured rubber tapper from China and India altered Malaysia’s ethnic composition forever. The introduction of new crops like corn and sweet potatoes from the New World had a dramatic impact on demography. For example, the growth of population in China, which had been held in check by the shortage of irrigable rice fields, got a boost from new crops that could be grown on marginal soil. Similarly, Chechnya’s population grew apace after the arrival of corn from the New World.

From the Roman empire, to Pax Britannica two centuries ago, to the Pax Americana of today, the power of super states has been another force changing the nature of interdependence. In the emerging global supply chain that now feeds consumer production worldwide, Western and American multinational corporations have taken a lead role.

The expanding circle of free trade has boosted economic growth and spawned a burgeoning middle class, which, in turn, has increased consumption of globally produced goods and rise in international tourism. Most striking have been the world’s two most populous countries, China and India. With rising income and greater consumption has come more personal freedom and a growing demand for accountable government. Even though the vast majority of the world population is still poor, the ideas of democracy, human rights and press freedom have spread. The percentage of countries which hold multi-party elections to choose their governments has grown from less than thirty percent in 1974 to over sixty percent of the 192 countries in the world.

The most powerful force for transmitting the ideas of democracy and human rights across borders is the revolution in information technology in the second half of the 20th century. The telephone, television and the Internet have been the key tools. In the late 19th century, it took Queen Victoria sixteen and a half hours to send a message of greeting across a transatlantic cable to President James Buchanan. Today vast amounts of information in multiple formats - text, voice, video - are transmitted at the speed of light. Moreover, a three minute call from New York to London costs less than a dime, instead of the $300 it cost in 1930. This dramatic drop in the price of telecommunications has made the benefits of the information explosion available to much of humanity.

Meanwhile, innovations like satellite television have connected people’s emotions across borders and oceans: the news of Princess Diana’s death flashing on cable TV’s immediately elicited wreathes of flowers from around the world. The free flow of information is also helping bridge the political divide: September 11 triggered a candlelight vigil among young Iranians. But it has also been hardening attitudes along ideological boundaries. The Arabic-language satellite station Al Jazeera’s live broadcast of Israeli-Palestine violence has widened the gulf between Arabs and Israelis.

The falling cost of communications and transportation has boosted economic growth while literacy and better health care have improved quality of life. People the world over are living longer and healthier lives, while the number of people living in poverty has dropped in most regions (though it has increased in Africa and South Asia).

Yet faster growth has its cost, too. The reduction in poverty worldwide has negative environmental consequences. Close to one percent of the world’s rainforest is disappearing every year because of expanding agriculture and trade in forest products. The closely knit global communication network that makes growth possible has also made the world as a whole more vulnerable to everything from disease and mischief to terror. HIV infection in humans developed in Africa and South America but has spread to the entire world, now infecting some 14,000 people each day. In 1997, in barely five hours the “I love you” computer virus released by pranksters in Manila wreaked $700 million worth of damage worldwide. The September 11 hijackers made use of electronic transfers of funds to finance their operation. They also relied on the Internet to coordinate their moves and buy airline tickets. Since the attacks, Osama Bin Laden’s favorite means of communicating with the world from his cave has been satellite TV.

Not that any of this mixture of the good and the bad is new. Throughout history, the introduction of breakthrough technologies has brought disruption, and created winners and losers. When the Old World connected with the New World through colonizers and explorers, new pathogens like small pox and influenza caused a “demographic holocaust,” killing three out of every four Native Americans. The colonization of the Americas and vast parts of Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America, has destroyed traditional social structures and political power while speeding up the process of economic integration. The need for labor to mine silver and work the plantations resulted in the transfer of some 10 million slaves from Africa. On the other hand, the economies of Europe and Asia boomed, fuelled by the flow of precious metals and new commodities.

No other country has played as significant a role in reconnecting the world as the United States, itself an early product of modern globalization. A vast majority of some 60 million people who left their place of birth in the most intense period of globalization in the late 19th century went to the US. Immigrants and slaves built the richest nation in history. They drew upon world resources - starting with the water mill and steam engine technology from Britain - and emerged as a leading innovator and the most potent engine of globalization. With the American victory in the World War II Pacific arena and the launch of the Marshall plan, US economic and military power has spread to far corners of the world, culminating in the end of the Cold War. The fall of the Berlin Wall symbolized the end of a global ideological division and gave a boost to the latest burst of globalization itself. It is no wonder many around the world see - and resent - globalization as a euphemism for Americanization.

At the same time, the end of the Cold War has brought into sharper focus the other huge chasm that exists between the rich and the developing nations. While globalization has created unprecedented riches, many people have also been left mired in poverty. Industrialized countries with developed infrastructure, institutions and education, and middle income countries which opened up the economy have benefited most from globalization, but the poorest countries have not grown, or in some cases have even sunk back. Thus despite the overall fall in the rate of poverty, close to a third of the world population still lives in utter poverty without access to electricity or drinking water. The gap between the rich and the poor countries and between the wealthy and the indigent within countries has also widened. The rules of global engagement that have evolved, and the institutions that manage them - from the International Monetary Fund to the World Trade Organization - reflect the power imbalance between wealthy and poor nations.

Thanks to the wider diffusion of information, today’s have-nots are more aware of the gap between themselves and the rich West, and between themselves and Western-backed domestic elites. This consciousness can be a powerful source of resentment and protest, such as the anti-American demonstrations from Venezuela to the Philippines. Overt or subliminal political and cultural messages carried with goods, ideas and entertainment from the developed world have added to the sense of disruption in many traditional societies. Combined with the misery and misrule in many countries, the bright lights of the West lure many to seek their fortunes elsewhere. The rising tide of illegal immigrants washing over the developed countries has become a major concern. The reconnection of the world through goods and ideas has also evoked conflicting responses - from admiration to bitter nationalistic and religious resistance. While students in Iran clamor for an American-style life, many in the West oppose globalization as the symbol of iniquitous free market capitalism. Many people around the globe also see a Western-led globalization aimed at destroying Islam.

What does all this mean for globalization? Will globalization be forced to retreat in the face of growing disillusionment and dangers such as terrorists’ who abuse open borders and easy economic transactions? There is, of course, a precedent for such a decline in globalization. Between the two World Wars, free trade and the free movement of people did slow to a crawl, thanks to the raising of tariff walls and a closed door to immigration. But those restrictions did not dampen the same four basic motivations - conquest, search for prosperity, proselytizing and curiosity - that have driven globalization. The Allied victory against the Nazis and Japan, in fact, reopened the flood gates of globalization, giving a further boost to trade and travel.

To be sure, many issues could throw a wrench into the engines of international integration - issues like the growing anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe, the West’s farm subsidies and intellectual property rights concerns, and the tightened visa policies of the US since Sept. 11. However, the secular trend of people connecting with the world would be hard to reverse. The search for prosperity still drives businesses to expand beyond their borders and consumers to buy the best at an affordable price, irrespective of the country of origin. The same curiosity about others that led the likes of Ibn Batuta to leave home leads millions to travel, to watch foreign movies, eat different foods and enjoy international music and sports events. The biggest difference between the globalization of the past and that of today lies in its visibility and speed. The accelerated speed of global interaction has telescoped its impact and the global spread of the media has made it instantly visible - something that in the past happened in slow motion and often out of sight. With all its promises and pitfalls, the historical process of reconnecting the human community is here to stay and increasingly visible and increasingly a challenge. Our task - whether we are citizens, scholars or statesmen - is to understand and manage globalization, doing our best to encourage its favorable aspects and keep its negative consequences at bay.

Nayan Chanda is editor of YaleGlobal Online. His essay does not reflect the view of the Center for the Study of Globalization.

© Copyright 2003 Yale Center for the Study of Globalization.