All Fall Down

All Fall Down

WASHINGTON: On Monday, after a meeting designed to give the Doha Round one last try, World Trade Organization Director-General Pascal Lamy admitted failure and suspended not only the meeting but the Round itself. "There are no winners and losers in this assembly," he glumly observed, "Today there are only losers." In truth, the real losers are those whose representatives were not in the hall and could only watch the breakdown.

Charged by Lamy with saving the Doha Round, trade and agriculture ministers from the US, the EU, Japan, India, Brazil and Australia assembled, only to break up a day later in quarrelsome disarray. The participants – as well as some who stayed away – do indeed emerge damaged. But their countries are not losers. Doha agreement or not, trade among the big countries is booming, their growth rates rising, with unemployment lines shortened. The wealthy nations can live with a stalemate.

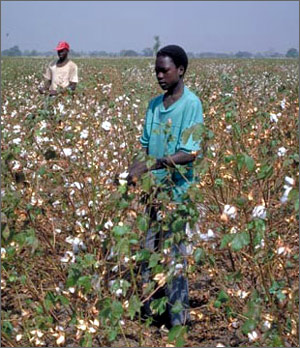

The real losers are cotton farmers in West Africa, textile workers in low-income Asian and Muslim states, and low-income shoppers in the poorest quarters of America and Europe. The Doha Round was supposed to help the world’s poor, by lowering subsidies that keep Mali’s cotton out of textile mills, tariffs that limit the flow of Cambodian T-shirts and other clothes to shelves. The big countries had a chance to help the poor and flopped.

In the background to Monday’s failure – perhaps part of its cause – lurk six decades of success. Over these 60 years, the trading system’s members concluded 12 big multilateral trade agreements. The first, in 1947, was a modest effort to reduce tariffs on miscellaneous items like cash registers, glue, zinc, chocolate, rails and so on. Then 11 more agreements followed, the most recent dating to 1997 and 1998, dealing not with familiar tariffs but financial services, telecommunications and electronic commerce.

During this time, trade grew from $10 billion to $12 trillion. Exports were the equivalent of 5 percent of the $200 billion world economy of 1950, and now account for 60 percent of a $60 trillion economy. Allied leaders who launched initial talks, hoping to break open the closed world of the Depression and ease relations among the great powers, would probably be gratified by the result.

But success has created a nasty inequity. There is no reason to excuse the Geneva negotiators for failing to fix it, but it is only fair to observe that their task was difficult.

About $11 trillion of the $12 trillion in exports move swiftly and easily around the world. By now, barriers to trade in sophisticated manufactured goods, high-tech products, natural resources and tropical products are inconsequential or gone. Services industries move even faster, using the internet, satellites and fiber-optic cable to reach around the world.

The last trillion dollars or so is more sluggish. These are older industries – agriculture and textiles in particular, but also fisheries, leather and sports equipment. Here, trade barriers remain common and high. The OECD’s $300 billion farm subsidy count is nearly half the annual $700 billion in farm exports. Tariffs on sugar, meat, juice and butter commonly rise to 50 and 100 percent. Rich-country tariffs on clothes are often 10 and 20 percent, with those of big developing countries sometimes much higher.

Trade negotiators left these industries for last because – especially in farming and fishing – they often reflect national identity and political favor. The result – trade policies in almost every big country are easy on rich countries, but tilt steeply against poor countries that specialize in food and clothes, and against poor people who spend greater proportions of income on life necessities.

The Doha Round's hope was to fix the inequity. After five years of talks, with the US government's trade negotiating authority running down, Lamy told the negotiators that they faced a "moment of truth." As it turned out, the truth was that the negotiators were not up to the task.

The Bush administration insisted that it could not make big cuts in farm subsidies unless the EU sharply cut its agricultural tariffs. Europe argued that the US should cut farm subsidies before demanding more tariff cuts of Europe. Both said the big developing countries should agree to steep cuts in manufacturing tariffs. Brazil and India expected the richer countries to do the most and soon. All make good points about their partners’ flaws. None, except Australia, was willing to admit its own shortcomings.

The Bush team argued that America has relatively lower farm subsidies and tariffs than Europe or Japan. True enough – but demands for deeper subsidy cuts from the US reflect the administration’s sharp 2002 increase in US farm programs. Had it agreed to reduce the programs to the levels inherited from the Clinton administration, all might be well.

The EU looks no better – failing to pass its constitution last year, it now blocks farm trade reform to help the poor – and much the same can be said of Japan. Nor do Brazil and India have much reason for pride – successful exporters and fast-growing economies, they often treat poorer and smaller neighbors even more harshly than the rich countries do. And China, the world’s most dynamic big economy, chose to take no risk to support the system at a critical juncture.

More important than blame, though, is the direction for the future.

Lamy has reason to be glum. Farmers and seamstresses, as they read his gloomy speech in the newspapers of Bangladesh and Honduras, or listen to it on the BBC’s Niger service, are right to feel as though the big players let them down.

But neither Lamy nor they should despair. The WTO and its predecessor, the GATT, have had breakdowns before, if never quite on this scale. Their members always rebounded. They can do so again, and might start with two ideas:

First, members must provide some practical, smaller-scale help for the poorest countries. All the big economies pledged in December 2005 to give duty-free treatment to goods from the world’s “least-developed” countries – sub-Saharan Africa, the Pacific islands, Haiti, Afghanistan, Yemen, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Laos and East Timor. Europe and Japan can start with a meaningful gesture on farm products.

The US Congress should renew a textile benefit in the African Growth and Opportunity Act, and improve the Bush administration's hedged offer to abolish tariffs on 97 percent of goods from the poorest countries. This is one of those ideas that sounds good, but can be very tricky. The US divides products into about 11,000 types, each with its own "tariff line." The least-developed countries produce only a few of these goods. By excluding only 330 tariff lines covering textiles and farm products, the administration could keep virtually all imports from Afghanistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Cambodia off the duty-free list.

The other course is a more engaged, serious involvement by the heads of governments. The collapse of the Geneva talks proves, at minimum, that trade negotiators cannot do the job alone. They need public support, and for this they need the leaders to level with their citizens not only about the sins and flaws of foreign countries, but in their own policies as well. The issue is too important for leaders not to come clean. An honest admission of the issues at stake is what the WTO – not to mention the world’s poor – needs most.

Edward Gresser is director of the Progressive Policy Institute’s Project on Trade and Global Markets.