Anxious America – Part II

Anxious America – Part II

NEW HAVEN: The US once had a working formula for innovation. Inventors imagined products, factories efficiently transformed ideas into reality, and businesses adapted, creating millions of jobs along the way.

Yet an anxious America, with its intense security concerns about terrorist infiltration and technology leaks, along with fears about losing jobs to immigrants, discourages many potential innovators. Unless current restrictions are eased or a concerted effort is made to encourage science and technology education among American students, the US will face economic crisis.

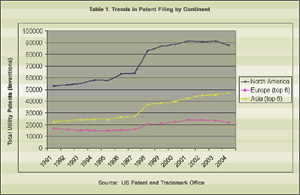

Notwithstanding Microsoft, Apple or Google, several indicators point to the decline: First, US students have little interest in science or engineering as a career. Second, patents filed by US inventors have started to decline, whereas patents from Asia are steadily increasing. Third, US manufacturing employment peaked in 1979, and shop-floor innovation vanishes as companies make more consumer products overseas. Finally, companies scramble to secure more overseas talent, and a survey soon to be released by the Kauffman Foundation reports that 40 percent of 200 multinational corporations plan relocating some R&D within the next three years, many preferring expansion in India and China.

For now, students from Asia, Russia and Eastern Europe keep US college math and science programs afloat. About half of all science students are non-US citizens, reports the US Council of Graduate Schools, but applications from Chinese and Indian students declined by 15 and 5 percent, respectively, in 2005 from the previous year. Australia, the UK, Singapore, even China, lure students who would have once studied in the US, and after graduation, stayed on to work. Alarmed about fewer students pursuing science and postdoctoral research, universities protest the visa restrictions and background checks.

But security measures remain bureaucratic, so universities also head to the countries with eager students. State universities of Florida, Texas and Michigan are among the dozens that have started operations in China and India. Students who would have once started careers in the US stay overseas.

US employers struggle to hire foreign scientists, too, because of fears of exacerbating unemployment. The US Immigration Act of 1990 formalized the visa program to attract professionals to specialty occupations, especially in science and math. Universities like Harvard and Yale, firms like General Electric and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and public research powerhouses like NASA and Los Alamos National Laboratory recruit hundreds of scientists who hold the visa known as H-1B. India, China and Canada are the leading contributors of such employees, and many workers eventually apply for citizenship.

Yet politicians, buffeted by demand from special-interest groups, debate the value of the H-1B. So the annual cap has jumped up and down over the years: When the investment climate was hot, industry persuaded politicians to raise the number; in hard times, labor interests demand reductions. The cap was originally set at 65,000 in 1990. Amid fear of massive computer outages associated with Y2K, Congress swelled the cap to 195,000 for three years starting in 2000. Then the cap returned to 65,000, with special deals for Chile, Singapore and Australia, disguised with different letters and numbers. Education and nonprofit research institutions have always been exempt from the limit. In fiscal years 2005 and 2006, visa caps were reached on the first available day.

Initially the biggest obstacles for foreign scientists willing to work in the US were the visa caps and fees of thousands of dollars, often not covered by companies. Since 9/11, visa applicants undergo a two-prong background check. First, the US Department of Labor certifies that no willing or qualified Americans are available for the position, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the US Immigration and Citizen Services run the same screening performed for those applying for citizenship or permanent residency. For FY 2003, DHS approved 94 percent of the applications.

The visa program has its critics. Some complain that the program encouraged a brain drain by removing talent from developing countries. Others complain that the arrival of foreign scientists depresses US salaries.

So US politicians juggle the number of visas, debating whether more or less of them will actually increase the nation’s pool of scientists over the long term. Two opposite drives are underway in the US Congress: The House of Representatives would like to restrict the visa program, while the Senate would welcome more foreign students to the US. Companies lobby Congress for higher caps, particularly for scientists with advanced degrees.

Increasing the visas may not bring the best scientists to the US. Foreign professionals anticipate hostility in a US anxious about job security and national security. And domestic and foreign scientists alike share anxiety about the high cost of living in science-driven communities like Boston or northern California. Post-doctorate scientists earn less than $50,000, while the CEOs who find new ways to manipulate profits earn millions.

More parents urge students to think twice before pursuing a science career. US unemployment statistics are hardly encouraging: According to the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, unemployment for engineers has risen from 1.4 percent in 2000 to 4.3 percent in 2003; for computer scientists, from 2 percent in 2000 to 5.5 percent in 2004.

The anxiety in the US could mean more scientists, even US citizens, will seek opportunity elsewhere. Take Atique Rahman, a native of Bangladesh, who was an early H-1B applicant. After earning a doctorate degree in biochemistry from Oregon State University in 1989, he worked at the Roche Institute of Molecular Biology in New Jersey, cloning a gene for an enzyme. He then joined Yale University in 1992 as an associate research scientist in digestive disease with the Department of Internal Medicine, where he cloned another gene.

His research did not offer immediate applications, and he left academia. After the failure of a business venture, unrelated to his research, he returned to biotechnology in 2001, but this time in Bangladesh, where he develops a biotechnology education program.

A 2005 report from the American Electronics Association confirms that Rahman’s decision is part of a trend for other countries of the subcontinent: “The highly skilled, Indian-born talent that once flooded to the US is now returning home, turning America’s brain drain into India’s brain gain.”

The net effect of shutting the door to foreign scientists, the homeward journey by others, could mean less international recognition for the US. Half of US Nobel physics and chemistry laureates in this century were born in foreign countries or of foreign parents, and a recent World Bank report suggests that every 10 percent increase in foreign graduate students leads to a 6 percent increase in patents.

Of course, most patents do not carry the value of electricity or broadband inventions that revolutionize everyday life. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development notes that US creation of high-value patents has been stagnant since 1996.

High-value innovations do not emerge in a vacuum. Creating an environment that recognizes creativity – and high-value invention – requires nurturing and respect. Closing the door to scientific talent out of fear and suspicion, discouraging scientists through neglect and low wages, is not how the US should alter the disturbing trends – falling numbers of students, scientists and patents – that will eventually erode prosperity.

Susan Froetschel is assistant editor of YaleGlobal Online.