Asia Caught Between Rivals China and US

Asia Caught Between Rivals China and US

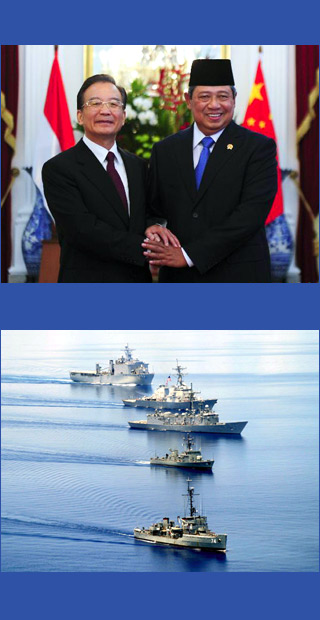

HONG KONG: As Europe dithers and the US nervously watches its unemployment rate, a China-led Asian rise is accepted as the new reality. Less noted is the anomaly of an Asia increasingly integrated with the Chinese economy and militarily more reliant on the US.

At a retreat in Hayman Island, Queensland, for Australian CEOs, a security expert noted that this is the first time in Australia’s history that its major economic partner is not concurrently major strategic partner – initially the UK followed by the US.

China has become for Australia, as it has for many nations in Asia Pacific and indeed around the world, especially those engaged in commodity exports, its key engine of growth. Yet Australia has been one of the US’s closest strategic and military allies, from World War II to Korea to Vietnam and Iraq. The planned stationing of 2500 US troops in Darwin, reflecting the Obama administration’s tilt to the Pacific, is meant to consolidate these ties. The US and China are not belligerents, yet rivalry is growing. Being between the two is uncomfortable to say the least.

There are many hotspots, perhaps hottest of all the South China Sea, which Beijing has declared to be part of its “core interests” with Washington insisting on freedom of navigation. Besides competing claims to resources, there are disputes over nomenclature. The Vietnamese, for example, whose relations with China are among the tensest in the region, resent the name used by the West and perception of giving in to a Sino-centric perspective. The Vietnamese call it the Eastern Sea. In a recent confrontation between Chinese and Philippine vessels in the Scarborough Shoal area, Beijing claims it as part of its territorial waters in the South China Sea. Manila prefers the West Philippines Sea.

Many in the Asia Pacific region regard the concept of China’s peaceful rise with skepticism. The Philippines has been a longstanding ally of the US, and even Vietnam, erstwhile enemy, increasingly looks to Washington for protection. Since the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, America’s military presence in Southeast Asia has been, on balance, benign and welcome. At the same time, the region’s economies have become increasingly dependent on China.

At $362.3 billion in 2011 China has recently overtaken Japan as ASEAN’s third biggest trading partner, after the EU ($567.2 billion) and the US ($446.6 billion). However trade between China and ASEAN is growing faster: a 24 percent recorded increase in 2011. Reflecting this growing relationship, in January 2010 China and ASEAN concluded a free trade agreement – CAFTA. In population terms, it’s the world’s biggest market and, in GDP, third biggest.

The actual physical US military presence in terms of troops in the region is concentrated in Korea and Japan, with small numbers in Southeast Asia – the Philippines, 142; Singapore, 163; and Thailand, 142. However US influence is being strengthened especially through the American naval Pacific Command. Main ties are with Australia, the Philippines and Singapore with upgraded military with Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei.

Moving north to the Korean Peninsula, Pyongyang has just failed in its initial attempt at launching a long-range missile. Consequences of this loss of face remain an unsettling mystery. Also mysterious is the exact relationship between Beijing and Pyongyang and the degree of PRC influence. For Seoul, this is not a matter of sheer academic interest. Korea’s share of trade with China, at 27 percent, is greater than that with Japan and the US combined, 8 and 11 percent, respectively. There has not been a peace treaty to conclude the Korean War, only an armistice, and in view of the Orwellian nature of the North Korean regime and its apparent nuclear ambitions, the Korean peninsula stands out prominently as one of the most likely theaters of military conflict in Asia. Thus Korea depends arguably more than any other Asian nation on the US for security. The number of US troops stationed in South Korea – 28,500 – ranks third in parts of the world without conflict after Germany, 53,766, and Japan, 39,222.

In the first half of the 20th century, Japan emerged as Asia’s greatest economic and military power. From 1932 with the establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo until Japan’s defeat in September 1945, Tokyo sought to establish its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. After Japan’s surrender, the American occupation initially sought to chastise and weaken the country both militarily and economically. Following the Communist victory in China in 1949 and the Korean War, the US rapidly sought to help Tokyo rebuild the economy and turned the country into a passive but loyal, acquiescent ally. Japan did not fight in either the Korean or Vietnamese wars – in good part because of its “peace constitution” imposed in early years of US occupation – but provided vital logistic and material support.

Throughout the decades Tokyo has acceded to US demands. Japan became the world’s second biggest economic power and by far Asia’s largest. But given the war memories, Tokyo followed what it referred to as a low-profile policy in Asia in the second half of the 20th century. Most striking in this century, especially since China overtook Japan as the world’s second economic power, is how invisible Japan had become. In forums and conferences on Asian issues, Japan is often absent, mentioned only in passing.

Japan’s economic dependence on China, with China having surpassed the US since 2008 in becoming Japan’s biggest trading partner at over 20 percent and fastest growing destination for Japanese outward investment is deep. Exports to China – mainly capital and intermediate goods as China emerged as hub of Japan’s global supply chain – is a rare dynamic force in an otherwise anemic economy. Japan has also multiple issues with China, including over territory, notably confrontation over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, and in economic matters, a recent example being China’s ban on export of rare earths to Japan required for its high-tech manufacturing industry.

In Southeast Asia, Japan or the Korean peninsula, one notes the same dichotomy between economic reliance on China and military tension with it. Without resolving this contradiction, none of the Northeast Asian countries, China, Korea or Japan, can play a leading role. Hence most of the onus for institution building has fallen on ASEAN, the organization of 10 Southeast Asian nations. There has been a proliferation of initiatives, such as ASEAN + 1, ASEAN + 3, ASEAN + 6, the ASEAN Regional Forum ARF, the Chiangmai initiative, the East Asian Community and more. This reflects what’s referred to as ASEAN centrality. Much of the deliberations in the formation of these initiatives involve who to include and who to exclude, while seeking to involve China but not offend the United States. This is the case with efforts to establish the Trans Pacific Partnership, pushed by Washington. Tokyo, Seoul and other Asian capitals hesitate in light of China’s apparent exclusion – hence, the conundrum as countries find themselves between a rock and a hard place.

The situation in Asia Pacific is perilous and unsustainable. Under these conditions, it’s highly unlikely that robust regional institutions will emerge in the near future. And the fact that much of China’s economic prowess depends to a considerable extent on the big American market and investment opportunities put additional wrinkles on triangular US-Asia and China relations. With weak global governance and leadership, the Asia Pacific Region for all its economic success keeps floundering on uncertain seas.