Behind the Iron Curtain

Behind the Iron Curtain

NEW YORK: Recent reports from North Korea about the new leader, Kim Jong Un, and his “openness” are tantalizing. Coming months will show if the optimism is warranted.

However, any possible transition in North Korea is not likely to follow the patterns of Arab Spring. Granted, refugees report that the citizenry in North Korea is under attack by state security and police agencies. But two key differences between North Korea and the Arab world stand out:

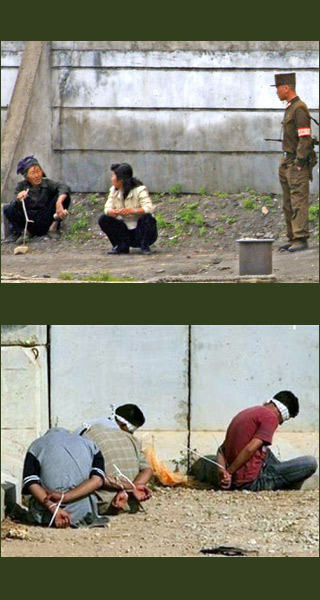

First, attacks against citizens in North Korea do not take place in front of CNN or BCC cameras. North Koreans are not armed with mobile phones and internet connections. In the DPRK, only the political and economic elites have cell phones, and these cannot make international calls. North Korea has a nationwide intranet, but the few citizens with computers cannot access the internet. Civil society organizations and social media are prohibited, and interrogations and attacks take place in remote, extra-judicial political penal labor camps, prisons and police stations. The government prohibits access for tourists, reporters and North Koreans, except those who work as prison guards.

Second, the state-directed political violence in North Korea cannot be documented in “real time.” The world often learns about brutalities of forced-labor camps and prisons two or even four years later.

The victims of regime violence must wait long after their release or the occasional escape to tell their stories. The former inmates spend months in North Korea planning escape to China, where once again they spend months or years earning the money and making connections for a long “underground” trek from Northeast China through Southeast Asia before claiming asylum at the South Korean, ROK, embassy in Bangkok, Thailand. Once in South Korea, the former North Koreans go through several months of intelligence debriefings with the South Korean government. Only then do journalists, scholars and human-rights investigators interview the victims of North Korean atrocities.

Notwithstanding the delays, knowledge of conditions in North Korea is growing exponentially. In 2002, some 3,000 North Koreans had fled to China and made their way to South Korea, including a score who had been imprisoned and subjected to forced labor under harsh conditions for political offenses. By 2010 and 2011, the number of North Koreans escaping to South Korea had exceeded 23,000, including hundreds who had been imprisoned, tortured and enslaved in violation of international norms and standards. Testimony from hundreds of former victims and witnesses about persecution, extra-judicial executions, slave labor, torture and other inhumane acts of comparative gravity reveal the severe repression that’s the heart of the DPRK citizen-control mechanism.

Former North Korean state security agency officials and former prison camp guards who defected to South Korea report that some 150,000 to 200,000 North Koreans are sentenced to lifetime forced labor in the kwan-li-so political penal labor colonies – victims of a broad but brutal, preemptive cleansing campaign, based on politics and ideology. Deemed unfit for the “Kim Il Sung nation,” the prisoners are persecuted for wrong-actions, wrong-thinking, wrong-knowledge or wrong- associations.

Persons suspected of real or imagined wrongdoing include those on the losing side of a dispute within the Korean Workers Party. Others failed to take proper care of mandatory Kim Il Sung photographs or went to China without authorization in search of food or employment.

Persons suspected of wrong-thinking can be Christians who oppose messianic deification of Kim Il Sung or orthodox Marxist-Leninists who oppose introduction of Juche ideology or dynastic succession as contrary to the tenants of Marxism.

Those guilty of wrong- knowledge include many of the Korean-Japanese who migrated to the DPRK from Japan in the 1960s or North Korean diplomats or students who observed the collapse of socialist allies in Eastern Europe. Awareness of capitalist democratic prosperity in Japan or the collapse of state socialism was deemed dangerous to the regime.

People with wrong associations account for the largest number of inmates in the labor camps: These include family members of wrongdoers and wrong-thinkers – wives, children and even grandchildren – because the DRPK revived the feudal “three generation, collective responsibility, guilt-by-association system.” Family members are sent to the prison camps with the explicit intent to terminate family lineage. Children and grandchildren of real or imagined dissidents can anticipate short lifespans, a result of malnutrition, disease, accidents and forced labor in mines, forests, collective farms or factories for their family’s presumed disloyalty to the Kim dynasty.

The former prisoners from the kwan-li-so labor camps are not charged, tried, convicted or sentenced according to the DPRK criminal codes and criminal procedures codes. Instead, they’re “forcibly disappeared” by police agencies and deported to the camps with no legal or judicial process. Only a small number of inmates are eligible for eventual release. Those who escaped to South Korea report public executions of prisoners for attempting escape or violating camp regulations, mostly unauthorized food gathering.

In addition, thousands of North Koreans are imprisoned, subjected to forced labor for both criminal and, by international standards, political offences.

Since 2003, the UN Human Rights Council and, since 2005, the UN General Assembly, at the initiative of member states of the European Union, have passed resolutions that recognize gross violations of internationally recognized human rights. Each year, the number of UN member states voting for the DPRK human rights resolutions increases.

In response, North Korea insists that the political prison camps do not exist and that “there can be no human rights problem in their people centered socialism.” North Korea refuses to meet or cooperate with officials appointed by the UN Human Rights Council. Even during the height of the North Korean famine, when UN agencies were providing food aid to close to one third of North Koreans, the DPRK refused six requests to meet with the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food.

The UN Security Council has repeatedly sanctioned DPRK, but only for its nuclear weapons and missile programs. UN Security Council members have refused entreaties to take a more comprehensive approach on North Korea’s human-rights debacles, including famine of the 1990s, made worse by the government’s policies, and subsequent chronic, policy-driven food shortages.

Former political prisoners have now reached the sufficient critical mass in South Korea to form their own NGOs. More than 100 former prisoners and torture victims jointly articulated their grievances in December 2009, writing to the International Criminal Court, asking for an investigation into the crimes against humanity. The ICC prosecutor’s office responded that, absent a referral from the UN Security Council, the crimes referred to by these petitioners were outside the ICC’s jurisdiction. The prosecutor recommended that North Koreans approach other organs of the international community.

Subsequently, a coalition of some 40 international NGOs, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Freedom House, and other NGOs from South Korea and Japan, have joined forces with former North Korean prisoners to seek international recognition that the extreme violations of constitute crimes against humanity, thus encouraging North Korean authorities to realize that it’s in their interest to close the labor camps and political prisons.

For now, despite its thumbs-up to Mickey and Minnie Mouse, new DPRK leadership avows determination to seek out and punish traitors, including family members. The only recourse for those outside North Korea is to insist that the international community make dismantlement of forced-labor prison camps a priority on par with the dismantlement of the DPRK nuclear weapons program.

David Hawk is a former UN human rights official in Cambodia and former executive director of Amnesty International USA. He currently is a visiting scholar at the Columbia University Institute for the Study of Human Rights and teaches human rights courses at Hunter College, CUNY.