Beijing Unflustered by Cool Ties With Seoul

Beijing Unflustered by Cool Ties With Seoul

WASHINGTON: On July 3, South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade set up a chat-room on the ministry’s homepage to solicit input from the public on how to improve ties with China. That the government seeks citizens’ advice on how to relate to China two decades after having established diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic is a telling indicator of how troubled relations have become.

Of course, relations have blossomed in many areas. Bilateral trade has expanded dramatically since the two countries normalized relations, from roughly US$6 billion in 1992 to almost $190 billion in 2010. Tourist and educational exchanges have also grown quickly. Yet, contrary to South Korean hopes, expanded economic and cultural ties with China have not resulted in greater Chinese respect for Seoul’s foreign-policy priorities, leading to the foreign ministry’s quest for new approaches to China.

To date, much of the South Korean debate over relations with the PRC has ignored China’s fundamental policy differences with the ROK, focusing instead on relatively less important issues such as who the Korean ambassador to China is or how negative Korean attitudes towards Chinese imports might be eroding Seoul’s influence with Beijing. Yet China’s Korea policy is driven by much more substantial issues, including a desire to sustain the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or North Korea, as a strategic buffer; anxieties about China’s own regime stability and the legitimacy of its borders; and Chinese consumers’ growing appetites for seafood. In light of deeply-rooted policy differences, so clearly on display in China’s treatment of South Korea over the past two years, no amount of tweaking around the margins of policy, inspired by internet polling, is likely to lead to dramatic improvements in the bilateral relationship.

In recent years, China has repeatedly demonstrated its determination to protect North Korea as a strategic buffer. In March 2010, China’s North Korean ally fired a torpedo that sank the ROK Navy corvette Cheonan. Seoul’s requests that Beijing chastise the North for its actions were met with refusal, angering many in South Korea who had not appreciated the depths of Beijing’s commitment to North Korea. Instead of condemning the North, Beijing called on all sides to remain calm and acted as if China itself was the injured party when the US and South Korea announced plans to conduct naval exercises in the Yellow Sea aimed at deterring further Northern aggression. Through diplomatic bluster, in seeking to block the USS George Washington aircraft carrier from entering the Yellow Sea, China was attempting to establish a veto over foreign military activities in South Korean waters. Eight months after its initial attack on the ROK, Pyongyang shelled Yeonpyeong Island, killing two ROK Marines and two civilians; in the wake of this outrage, China once again refused to criticize the North.

This same strategic motivation has led the PRC to hunt down North Korean refugees inside China and return them to the DPRK in an attempt to prevent any exodus that might destabilize Pyongyang, an approach that angers South Koreans. More recently, China arrested a group of ROK activists supporting an underground railroad moving escapees out of the North, reportedly torturing them with electric shocks while accusing them of endangering Chinese national security. Despite its efforts to discourage South Korean human-rights activists from operating in China, Beijing’s recent agreement to allow 120,000 North Korean laborers to work in Northeastern China means activists are likely to return to the region in greater numbers, attracted by a new pool of potential defectors.

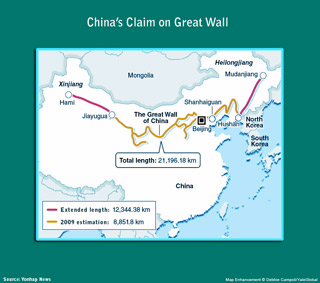

Beijing’s efforts to secure its present territorial boundaries by justifying them using questionable historical claims have also raised South Korean hackles. In June 2012 China announced that it had discovered that the Great Wall extends much further than was previously realized. The claim reinforced earlier Chinese assertions that large swathes of land historically regarded by Koreans as the proto-Korean kingdoms of Koguryeo and Balhae were actually within the Wall and thus part of ancient China. Disturbingly, Beijing’s strategy of using the past to serve political needs of the present may imply that China harbors designs on territories that lie in today’s North Korea, areas the South aspires to reunify with one day. Such claims have alarmed many South Koreans and impart potentially strategic implications to reports that Beijing plans to spend US$10 billion by 2015 expanding road and rail lines to its border with North Korea. Such links could be used move in Chinese forces in the event of a North Korean collapse.

Finally, as China’s population grows wealthier, they consume more seafood; as fishing stocks in waters close to China’s shores are being depleted, this leads to increasing intrusions by Chinese fishermen into South Korean waters. After years of waiting for China to rein in its fishermen, in the wake of the murder of an ROK Coast Guard officer in December 2011 by a Chinese poacher, the South Korean National Assembly made it easier to police the country’s waters by appropriating more resources for the Coast Guard, liberalizing the conditions under which force can be used, and raising penalties for illegal fishing. Improved law-enforcement capabilities may result in more tensions if they lead to more clashes between Chinese fishermen and Korean authorities.

Surprisingly, despite the long litany of legitimate complaints South Koreans have about their treatment by China, many Korean observers nonetheless lay the blame for the poor state of relationship almost entirely on President Lee Myung-bak. Arguing that the South’s ties with the US and Japan are too provocative or that the Blue House should not have adopted a tougher stance towards North Korea – an approach Beijing opposes – many South Korean progressives, and even some conservatives, argue that a new approach must be tried. For example, if progressive candidate Moon Jae-in wins the Korean presidential election later this year, he’s likely to ask Beijing for help rebuilding relations with Pyongyang. Similarly, a victory by non-party-affiliated progressive Ahn Cheol-soo would also likely lead to outreach towards Beijing, since Ahn has stated that Korean foreign policy needs to “keep a balance between the U.S. and China [because] to solve North Korean problems, we need the help of China.” Even conservative candidate Park Geun-hye, if she wins the Blue House, is likely to focus on trying to improve relations by pushing ahead with a proposed free trade agreement with China.

Yet Seoul’s problems with Beijing are driven by considerations that go well beyond the power of any South Korean administration to resolve on its own, even if it further expands economic cooperation or returns to the policy of unconditional economic engagement with North Korea and outreach to China. China’s concerns over North Korean stability, politically-motivated history claims and burgeoning demand for fishing resources – together with the fact that leading candidates for the Korean presidency all appear likely to increase Seoul’s diplomatic outreach efforts to China – mean that Beijing can wait a few months for a new, more solicitous administration to take office in Seoul without having to change any of its own policies.

Moreover, the PRC is in the midst of its own political transition, and policy initiatives to improve ties with South Korea are not a priority at present. As such, the foreign ministry’s chat-room initiative is likely to fail to develop high-impact ideas, and the next South Korean government will probably find that substantive policy differences with China remain extremely difficult to resolve.