Bold Action Can Still Save Doha Round

Bold Action Can Still Save Doha Round

CANCUN, MEXICO: Acting alone without regard for the feelings of other countries is generally seen as undesirable in international affairs. But that unilateralist approach may be the only way to save today's multilateral international trading system from disaster after the collapse of trade liberalization negotiations here. The United States and Europe should move at once and without regard for international opinion to make major cuts in their agricultural production and export subsidies that unfairly undercut the already minimal living standards of some of the world's poorest countries.

Such a move is essential at this moment not only as a matter of providing a badly needed boost to developing countries, but also because the failure of talks last week (September 14) poses a serious threat to the continued viability of the WTO and the main hope of generating the economic growth necessary to lift developing countries out of poverty. Without immediate and dramatic action, the trend toward bilateral and regional trade agreements is likely to accelerate. Indeed, US Trade Representative Robert Zoellick has already said this will be America's new strategy.

The problem with this is that although they are concluded under the soothing label of "free trade agreements," such deals are, in fact, preferential arrangements between the parties that by definition must discriminate against outsiders. But this is exactly the wrong direction, from the point of view of world welfare. Since 1948, the United States has led a continuous effort to create a non-discriminatory trading system that would embrace all comers. And this effort has so far been highly successful. Average tariffs levied by developed countries on industrial products have fallen to negligible levels, and soaring world trade has resulted in the Japanese miracle and the growth of the Asian "Tigers" (including now China), lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty. Yet, despite this success, free trade has not provided benefits uniformly and has not always worked as the text books say it should. Too frequently, trade has benefited the richest countries while leaving the poor behind.

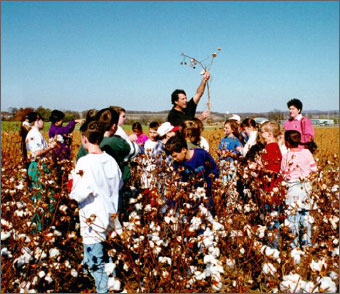

A major part of this problem has been trade, or the lack thereof, in agriculture. While the United States and other developed countries of Europe and Asia have largely opened their markets for manufactured and high-tech goods and services, in the area of agriculture – where 70 percent of developing countries make their living – they have practiced protectionism and subsidization. For example, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was supposed to open US markets to Mexican products, and it has done so in a wide variety of goods like autos and textiles. Yet, as a low cost sugar producer, even Mexico still finds itself virtually locked out of the US sugar market. Even worse is the case of cotton. In Muslim West Africa, where it costs 23 cents to produce a pound of cotton, the growers are abandoning their farms and fleeing to the crowded cities of Europe in the face of dramatically falling world cotton prices. Yet, in Mississippi, where it costs 82 cents to produce a pound of cotton, the growers are expanding their acreage and increasing their exports. In fact, it is the US exports that are driving down world prices and causing Africans to abandon their farms. How can they do this when their costs are so much higher than in Africa? In a word, subsidies – $3.5 billion annually to 25,000 US cotton farmers.

The Doha round of trade talks was specifically labeled the "Development Round" to emphasize the necessity of addressing this problem for developing countries. Both the European Union and the United States expressed a desire to solve the problem and indicated readiness to make some cuts in agricultural subsidies. At the same time, however, the Bush administration undercut its own position by passing a farm bill that dramatically increased the subsidies. To add insult to injury, in the Cancun talks both the EU and the United States made their proposed subsidy reductions conditional on further opening developing countries' doors to industrial exports and investment When a newly formed bloc of 22 developing countries said they were not ready to cope with these complex and, for them, largely extraneous issues, the talks collapsed.

As a former US Reagan administration "trade hawk," I understand the need as well as the desire to sometimes bargain hard. Moreover, the lowering of developing country tariffs on industrial goods and adoption of better rules for investment and competition would be good for the developing countries themselves. This is because they currently pay far more than necessary for many critical imported items and suffer from the fact that their current polices and practices are often harmful for their own industries as well as repellant to foreign investors. Nevertheless, in this case, the United States and the European Union should forget about tit for tat and just cut their production and export subsidies.

This is a situation in which, as experienced negotiators, we must recognize and accommodate the emotional elements of the situation and not let the "best" become the enemy of the "good." Yes, it would be best if the developing countries reduced their industrial tariffs and liberalized rules on investment, competition policy, and other matters while the developed countries cut their agricultural subsidies. But for decades, the developing countries have been sitting in the back row mostly watching as the US, Europe, and Japan have been making the rules. Unsurprisingly, the rules have been made to operate very much in favor of the developed countries. This is not to say that they haven't had benefits for the developing countries, but they certainly weren't primarily designed with the needs of the developing countries in mind. Over these years, the developing world has nurtured resentment as it watched more or less helplessly. Now, as a result of changes in the dynamics of the governance of the WTO, developing countries have been able for the first time to form an effective bloc with real power to push their own agenda aggressively. They are feeling their oats and taking satisfaction in being able to say "NO" to the developed countries, even if doing so isn't entirely in their own best interests. This may not be logical, but it is real. American negotiators should recognize it for what it is and go for second best, which is to give the developed countries what they want on agriculture and leave the other issues for another day.

Doing so would benefit US consumers by providing them commodities at prices far below those they now pay. It would also be good for the world economy, because it would spark growth by the developing countries and enable them to buy more developed world exports. This is even a situation in which there don't have to be any losers. Eliminating agricultural production subsidies does not have to result in loss of income for farmers. The subsidies could continue in the form of direct income support payments unrelated to production. Indeed, they could even be paid on condition that the farmers not produce the subject commodities. That way, developing world income could be increased while US farmers would at least stay even.

Most importantly, however, getting rid of production subsidies would set a tremendous example that would enable the Doha Round to reach a successful conclusion and breathe new life into the global trading system.

Clyde Prestowitz is the author of “Rogue Nation: American Unilateralism and the Failure of Good Intentions.” He is also President of the Economic Strategy Institute and was a trade negotiator in the Reagan administration.