Call for Inclusiveness May Not Work for Middle East’s Sectarian Divide

Call for Inclusiveness May Not Work for Middle East's Sectarian Divide

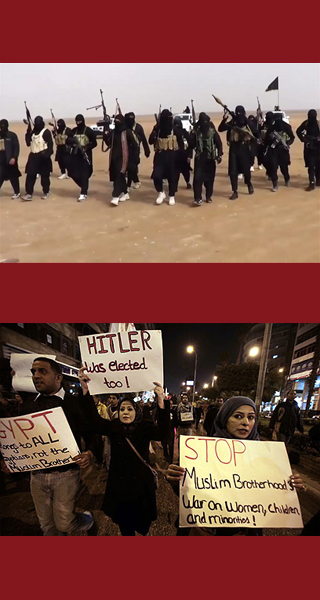

LONDON: Less than four months after being disowned by Al Qaeda because of ultra-extremist policies, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, ISIS, has captured Mosul. Unwilling to fight the lightly armed but fanatic 800 fighters of ISIS, two divisions of Iraqi soldiers fled. After occupying the airport, TV stations and the governor’s offices, the invaders robbed banks of $480 million in Iraqi currency and loaded 75 trucks with small arms and ammunition destined for Raqqa in eastern Syria, the capital of ISIS. Another 200 armed trucks and Humvees followed this convoy.

Alarm bells ring not just in Washington and Brussels, but also Tehran, Ankara and Amman. They had underestimated earlier signs of ISIS extending to Iraq its Syrian policy of administering seized territory.

Offers of assistance from US President Barack Obama followed along with the homily on the need of “inclusiveness” by the embattled Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. The Shia leader was told to reach out to the minority Sunnis who have felt alienated in the post–Saddam Hussein era inaugurated by the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Unsurprisingly, a sermon on the virtues of inclusiveness was also delivered by Washington to Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood after his victory in a free and fair election in June 2012. And when he was overthrown in a military coup in July 2013, Washington attributed his downfall to a failure to forge cordial relations with his erstwhile liberal and secular adversaries even when the latter showed little sign of accepting his victory.

Though well meaning, the repeated incantation of the inclusive mantra fails to take into account the historic chasm between Sunnis and Shias, or the conflict between the Egyptian state and the Muslim Brotherhood since its establishment 88 years ago. Western policymakers should ponder the Protestant-Catholic divide in Northern Ireland dating back to 1689 when Protestant King William of Orange fought Catholic King James II in Ireland. Political reconciliation between the two communities came after three centuries in 1997.

Whereas the Shia credo consists of five basic principles, the Sunnis have three. Shias and Sunnis share the religious duties of daily prayers, fasting during Ramadan, paying Islamic tithe and alms tax, and undertaking the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca; Shias add loving the Shia imams. Shia emotionalism finds outlets in mourning imams at their shrines: Ali, assassinated; Hassan, poisoned; and Hussein, killed in battle. Sunni Islam offers no such outlets for adherents.

Sunnis regard religious activities as the exclusive domain of the Muslim state. When the ulema, or religious scholars, act as judges, preachers or educators they do so under the state aegis. By contrast, in Shia Iran, the leading religious figures, titled grand ayatollahs, being recipients of the Islamic tithe from their followers, maintain theological colleges and social welfare activities independent of the state.

Contrary to popular belief, which holds Iran as the fountainhead of Shia Islam, it was Mesopotamia, later called Iraq, that was the bastion of this sect. All of 12 Shia imams were ethnic Arabs.

The ownership of Iraq alternated between the competing Sunni Ottoman Empire and the Shia Persian Empire until 1638 when the Ottomans annexed it. This put the Sunnis, a minority in Iraq, in control. They treated Shias as second-class citizens. This continued after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1918. Faisal bin Hussein, foisted on Iraq as king in 1921 by Britain, as the Mandate Power, was a Sunni. After the anti-royalist military coup in 1958, power passed to Colonel Abdul Karim Qasim, whose father was Sunni and mother Shia. He was assassinated five years later.

The seizure of power by the Baath Socialist Party led by General Ahmad Hassan Bakr, a Sunni, in 1968, put the minority sect firmly in control. This continued under Saddam Hussein, his nephew, from 1979 onward. When the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran emboldened Iraqi ayatollahs to speak up on behalf of their persecuted followers, Saddam brutally quashed Shia protest.

Against this background, US President George W. Bush invaded Iraq in March 2003 and overthrew Saddam’s regime. The 24-member Interim Iraqi Governing Council, nominated in July by the US-led coalition, reflected the sectarian/ethnic composition. The election to the Council of Representatives in 2005 under the new constitution, held under universal suffrage, exercised to the full, resulted in majority Shias gaining office.

Sunni discontent swelled. By 2007, sectarian violence threatened to escalate into civil war. But the Sunni tribal leaders’ severance of links with the Al Qaeda in Iraq and an infusion of additional US soldiers lowered Sunni-Shia tensions.

When Maliki became prime minister after the 2010 poll, he allocated himself the additional ministries of defense and interior. He appointed Shias to security posts, and squeezed out Sunni generals and leading politicians. In the April general election, his party won 92 seats on a popular vote of 24 percent, well ahead of the next group with 7 percent of the vote.

Whereas the Sunni-Shia division emanates from religious history, the tensions between the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian government are institutional. The Brotherhood was established in 1928 as youth club to bring about moral and social reform, but was politicized in 1939 by the accelerated arrival of the Jewish immigrants in Palestine under the British Mandate. The Brotherhood reinvented itself as “a Sunni way, a Sufi truth, a political organization, a scientific and cultural union, and an economic enterprise.”

The Brotherhood expanded exponentially during World War II with 500,000 members. Its volunteers fought in the First Arab Israeli War in 1948. Blaming Egypt’s political establishment for the debacle in that conflict, the Brotherhood resorted to subversive activities and was outlawed by the government in 1948. The ban was lifted in 1950, and the Brotherhood was allowed to function as a religious body. Its opposition to secular policies of the military government led by Colonel Gamal Abdul Nasser led to another ban in 1954.

Over the next six decades the Brotherhood’s fortunes have fluctuated, with periods of brutal repression by the state relieved briefly by uneasy tolerance.

Reversing Nasser’s policies, President Anwar Sadat (1970-1981) promised that the Sharia would be the chief source of legislation. He released Brotherhood prisoners, but fearful of its popular appeal, he denied it license to contest the 1976 election. Two years later, when he agreed to make peace with Israel without addressing the crucial Palestinian problem, Brotherhood leaders turned against him. In October 1981 four Islamist soldiers, belonging to a militant jihadist group formed by Brotherhood defectors, assassinated him.

After an intense drive to crush Islamic militants, President Hosni Mubarak engaged ulema to reeducate the imprisoned Brethren and other Islamists, two fifths of whom were university graduates or students. After the 9/11 attacks, pressured by Bush to democratize his regime, Mubarak allowed the Brotherhood to contest one-third of the parliamentary seats in 2005. It won 60 percent of the races. Mubarak flagrantly rigged the poll in 2010.

The 2005 blip in Mubarak’s fiercely anti-Brotherhood policy did not mitigate decades-long coaching of security forces and intelligence agencies to treat the Brotherhood as their number one enemy. It was therefore unrealistic to expect officers of these agencies to reorient overnight and serve a Brotherhood leader.

Against this backdrop of deep-seated division, the chance of the Obama administration’s call for inclusiveness finding receptive ears is as remote in Iraq today as it was with Morsi in Egypt. The historic conflict will play out much longer and outlast the patience of western democracies.

Read an excerpt.