Can Afghanistan and Pakistan Prop Each Other Up?

Can Afghanistan and Pakistan Prop Each Other Up?

WASHINGTON: With tensions mounting between Afghanistan and the United States over embarrassing errors of judgment and disagreements about means and ends, both governments now acknowledge that NATO is on its way home. The conversation about an early exit of US and NATO forces from Afghanistan has focused on numbers of soldiers, combat strategy, territory and ideology – and about whose policies have been thwarted, whose interests have been undercut, who cuts deals with whom and who will run Afghanistan when the West has left.

These questions are critical to the future of Afghanistan and its neighbors. They are also short-term, transactional and, ultimately, incomplete lenses through which to view a complex country and an even more complicated regional political economy that, after decades of war, is barely headed to recovery. After years of insisting that building the Afghan "nation" was irrelevant to Western aims, it turns out that building the Afghan state was precisely what was needed and what is dangerously lacking now.

The evidence, easy to find, is damning. Anticipating the departure of foreign troops, the World Bank and the Afghan government recently examined Afghanistan's post-NATO economic prospects and reported what insiders have known for a long time: The foreign military presence has driven international aid priorities, often to the exclusion of basic needs. Though skewed toward the military mission, this aid has been essential to the survival of the Afghan government and state. In NATO's absence and with deep donor discord about Afghanistan's future, civilian assistance is likely to diminish, too.

In fiscal terms alone, the transition from foreign to Afghan-led security will be challenging. The World Bank's Transition in Afghanistan: Looking Beyond 2014notes that aid financed $15.7 billion out of total public spending of $17.1 billion – a whopping 92 percent – in 2010-2011. This is a fraction of the cost of US funding for the military mission, as high as $444 billion as of the end of 2011, but as the Afghan government has stated correctly time and again, most military funds are spent in Afghanistan, but rarely on Afghans. NATO's pilot Afghan First Policy to encourage local sourcing for services and supplies arrived just as the alliance prepared to depart. Billions have been spent, but only a trickle was invested in Afghanistan's economic future.

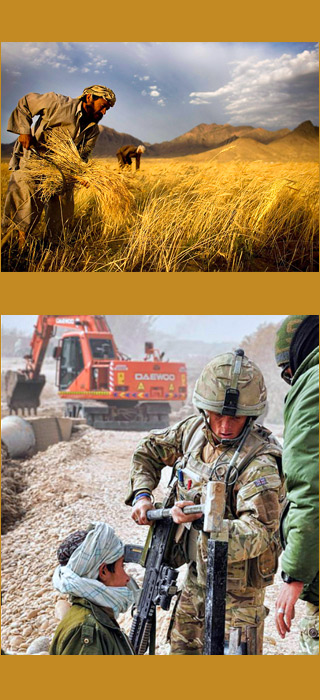

These despairing challenges are evident in the densely drafted 2012 United Nations humanitarian appeal for Afghanistan. "Afghanistan remains in a state of protracted crisis," it reports. And so it has, year after year. Humanitarian relief plugged some holes, but the ravages of violent conflict, civilian casualties and population displacement, recurrent natural hazards and poor governance all take an unremitting toll. Most Afghans will struggle on, tied to hardscrabble agrarian lives, affected only slightly by NATO's departure. Poor Afghans rarely saw any benefits from the last decade's aid to the security sector and to wealthier, more dangerous areas. For many, human security has become an oxymoron.

With security compromised by this huge financing shortfall, essential investment for development will become increasingly difficult. Afghan President Hamid Karzai's complaints about abuses committed by foreign security forces notwithstanding, it is already difficult, if not impossible, for aid organizations to function in insecure environments. Worse may come when troops leave. Crunch the numbers, and the same truths emerge: Without security, assistance disappears; without aid, the state barely survives.

An Afghanistan without money – or at the very least, taxable income to support necessary government functions – is not new. The small private sector contributes little to the state, reinforcing a fragility that, in turn, encourages a booming business in patronage and corruption. The very absence of a locally funded treasury is at once a symptom of instability and the potential cause for further conflict. A perilously underfunded and unstable Afghanistan, prematurely unmoored from NATO's security apparatus, is a danger to itself. It also invites continuing regional discord and cross-border predation, humanitarian crisis and tumbling economies in a quarrelsome neighborhood.

Afghanistan cannot live hand-to-mouth at the mercy of foreign donors. This admonition will sound familiar to those who followed Afghanistan's failed-state troubles in the 1990s. Karzai's early, ambitious development strategies were meant to build an increasingly self-sufficient state, but 10 years of war thwarted this goal. NATO's departure may provide the economic shock needed to persuade Afghans that an accountable and capable state is necessary to avoid future penury, and Afghanistan's neighbors – particularly Pakistan, still home to 2 million Afghan refugees – that helping to solve Afghanistan's economic woes is in its best interests, too.

That sounds like a lot for Pakistan's military to swallow. But endless interference across the border, meant to stabilize Pakistan's own security, hasn't worked: Military and civilian casualties are very high; insurgency has grown at home even as the army claims anti-Taliban victories along the Afghan border; and younger generations show little patience for a garrison state armed with intrusive intelligence officers, tone-deaf generals and corrupt politicians. Recent public opinion polls show profound dissatisfaction across the political spectrum and are forcing politicians, judges and, no doubt, some generals to rethink their roles and the nature of the state they’ve built over the past 60 years.

This is the political message that could drive new relationships between the two countries. The starting point is not encouraging, but the logic of change is.

Pakistan's economy, although larger and more diverse than Afghanistan's – Afghans can barely imagine Pakistan's per capita income of close to $3,000 – is not flourishing. The costs of war have hit the budget hard, the price of regional mistrust and instability are calculated in investment losses. These are the consequences of military adventures in Afghanistan s, and, many Pakistanis would argue, recent misplaced alliances with the United States. If Afghanistan can teach Pakistan anything, it is that security is not solely about armies, fighting doesn't fix poverty, closed borders won't stop frightened, hungry refugees – and spoilers inevitably lose the big battles.

The push for economic collaboration comes from Afghan and Pakistani businessmen even more than governments. Chambers of commerce have revived discussions about stemming smuggling, thwarting the flow of narcotics and growing bilateral trade. Both governments are discussing concrete proposals for transit and energy projects. This economic agenda is not new either: The United Nations proposed similar strategies more than a decade ago, and many deals have languished in recent years. But necessity provides a powerful push. When the presidents of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran met last week, their consultations about the business of war were typically acrimonious, more cordial when they got down to the details of their formal transit trade agreement.

Without NATO in Afghanistan and with an inevitably declining American presence in Pakistan, both countries have to rethink their bilateral relationship; with economics at the center, they stand a chance of succeeding where they have previously failed. This is one way to think seriously about how these two neighbors recover from the worst they have inflicted on one another.

NATO was always going to leave Afghanistan. The hard work now needs to be done where it is most needed – at home in Kabul and Islamabad.

Paula Newberg is the Marshall B. Coyne Director of the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University.