Can America Regain Its Soft Power After Abu Ghraib?

Can America Regain Its Soft Power After Abu Ghraib?

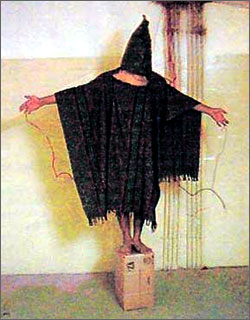

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS: The Iraq War has proven extremely costly in terms of America’s reputation around the world. Early images of “liberators” pulling down a statue of the tyrant Saddam Hussein have been replaced with images of American guards abusing prisoners in Saddam’s old prison, Abu Ghraib. Just as the picture of a naked girl fleeing a napalm attack achieved iconic status during the Vietnam War, so the picture of a hooded prisoner standing on a box with wires attached to his limbs has achieved a similar status in the case of the Iraq War.

Regardless of whether the behavior of the guards at Abu Ghraib is found to be typical or restricted to an aberrant minority, the image will linger. In part this is because wars of occupation are unpopular in a nationalistic age. But it also reflects the widespread feeling that the Bush administration was arrogant and unilateral in its approach to foreign policy in general and the Iraq War in particular.

Even before the Abu Ghraib photos were published, anti-Americanism had been rising around the world. Polls showed that the United States lost some thirty points of attraction in Europe in 2003, and America’s standing had plummeted in the Islamic world from Morocco to Indonesia. In 2000, nearly three quarters of Indonesians had a favorable view of the US. By May 2003, that had plummeted to 15 percent. In Jordan and Pakistan, a 2004 poll shows that more people are attracted to Osama bin Laden than to George Bush. Yet both these countries are on the front line of the battle against Al Qaeda. Clearly, the Bush Administration has squandered America’s soft power.

Soft power is the ability to get what one wants by attracting others rather than threatening with sticks or paying them with carrots. When you can attract and co-opt people, you do not have to spend as much on carrots and sticks to get the outcomes you want. Soft power is based on our culture, our political ideals, and our policies. If one thinks of Franklin Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms in the 1940s, of Jimmy Carter’s human rights policies in the 1980s, or Ronald Reagan’s appeals for freedom in Eastern Europe in the 1980s, all were investments in American soft power. But George W. Bush’s rhetoric about bringing democracy to the Middle East has not had the same type of appeal, in large part because it looked like a unilateral American imposition. Democratic values can be attractive and thus help to produce soft power, but not when they are imposed at gunpoint. The result is shown by the polls in the region. Being pro-American has become so politically toxic in the domestic politics of many countries that their leaders have to limit their cooperation with us.

Skeptics about soft power argue that anti-Americanism is inevitable because of our role as the world’s only military superpower. They regard popularity as ephemeral and advise us to simply ignore the polls. We are the world’s leader and should do what we determine to be in our national interest. As the big kid on the block, we are bound to engender envy and resentment as well as admiration. But the ratio of hate to love depends on whether we are seen as a bully or a friend. We were even more preponderant in the 1940s, but the Marshall Plan helped our soft power. Similarly, the United States was the world’s only superpower in the 1990s, but anti-Americanism never reached the levels that it did after the “new unilateralism” of the second Bush administration.

Can the United States regain its soft power? We have done it before. Anti-Americanism soared during the Vietnam War in the early 1970s, but we recovered within a decade. Not only did we change our policy in Vietnam, but the emphasis on human rights and freedom in Eastern Europe by Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan helped to emphasize attractive American values.

We will need to do a much better job in presenting our case to the world. We spend only a billion dollars a year on international broadcasting and exchange programs, about the same as France and Britain though we are five times larger. A bipartisan advisory group reported last year that our expenditure on public diplomacy for the entire Islamic world came to $150 million, which is equal to a few lines on the defense budget. If we spent merely one percent of the defense budget on public diplomacy, that would quadruple our investment in the instruments of soft power. There is something wrong with our priorities when the world’s leading country in the information age is doing such a poor job of getting its message out.

Of course, even the best advertising cannot sell a poor product. We will need to improve our policy product as well. Recovery of American soft power will depend on policy changes such as finding a political solution in Iraq, investing more heavily in advancing the Middle East peace process, and working more closely to involve allies and international institutions.

More specifically, we will have to deal with the abuses that were exposed at Abu Ghraib. Fortunately, we have begun to do that. Whatever our flaws as an occupying power, the symbolism of Abu Ghraib did not reduce the United States to the moral equivalent of the tyrant it replaced. Democracy matters. American abuses were widely published and criticized in our free press for all to see. Congressional hearings have made officials testify in public. And the American Supreme Court has asserted its independence from the executive branch by recently ruling that detainees at Guantanamo Bay and in military brigs in the United States must have access to legal representation.

One of the greatest sources of American soft power is the openness of our democratic processes. Even when mistaken policies reduce our attractiveness, our ability to openly criticize and correct our mistakes makes us attractive to others at a deeper level. Vietnam is a good example. When protesters overseas were marching in the streets against the Vietnam War, they did not sing “The Internationale”, but rather Martin Luther King’s “We Shall Overcome.” And that remains the best hope for those of us who believe that the United States can recover its soft power even after Iraq and Abu Ghraib.

Joseph S. Nye, Jr. served as the United States Assistant Secretary of Defense under the Clinton administration. He is distinguished service professor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government and author of “Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics.” In October 2004 he will publish “The Power Game: A Washington Novel.”