Can Asia Step Up to 21st Century Leadership?

Can Asia Step Up to 21st Century Leadership?

WASHINGTON: If one had any doubts about the world being in the midst of a huge power shift, events this month should have dispelled those. From Europeans appealing to China to save the euro to President Barack Obama arriving in Bali to lobby for Asian support, the transformation is evident. Less clear is who will lead the world in the 21st century and how. There is plenty of talk about the 21st century being an Asian century, featuring China, Japan and India. These countries certainly seek an enhanced role in world affairs, including a greater share of decision-making authority in the governance of global bodies. But are they doing enough to deserve it?

The intervention in Libya, led by Britain and France, and carried out by NATO, says it all. There is no NATO in Asia, and there’s unlikely to be one. Imagining a scenario in which China, India and Japan come together to lead a coalition of the willing to force a brutally repressive regime out of power, or undertake any major peace and security operation in their neighborhood, is implausible.

China and Japan are the world’s second and third largest economies. India is sixth in purchasing-power parity terms. China’s defense spending has experienced double-digit annual growth during the past two decades. India was the world’s largest buyer of conventional weapons in 2010. A study by the US Congressional Research Service lists Saudi Arabia, India and China as the three biggest arms buyers from 2003 to 2010. India bought nearly $17 billion worth of conventional arms, compared to $13.2 billion for China and some $29 billion for Saudi Arabia.

Chinese, Indian and Japanese foreign policy ideas have evolved: India has abandoned non-alignment. China has moved well past Maoist socialist internationalism. Japan pursues the idea of a “normal state” that can say yes to using force in multilateral operations.

But unfortunately, these shifts have not led to greater leadership in global governance. National power ambitions and regional rivalries have restricted their contributions to global governance.

President Hu Jintao has defined the objective of China's foreign policy as to “jointly construct a harmonious world.” Chinese leaders and academics invoke the cultural idea of “all under heaven,” or Tianxia. The concept stresses harmony – as opposed to “sameness,” thus signaling that China can be politically non-democratic, but still pursue friendship with other nations. China has increased its participation in multilateralism and global governance, but not offered leadership. This is sometimes explained as a lingering legacy of Deng Xiaoping’s caution about Chinese leadership on behalf of the developing world. More telling is China’s desire not to sacrifice its sovereignty and independence for the sake of multilateralism and global governance, along with limited integration between domestic and international considerations in decision-making about issues of global governance. Chen Dongxiao of the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies calls China a “part time leader” in selected areas of global affairs.

Japan’s policy conception of a “normal state,” initially presented as a way of reclaiming Japan’s right to use force, but only in support of UN-sanctioned operations, may sound conducive to greater global leadership. But it also reflects strategic motivations: to hedge against any drawdown of US forces in the region, to counter the rise of China and the growing threat from North Korea, and to increase Japan’s participation in collective military operations in the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf regions. Beset by chronic uncertainty in domestic leadership and a declining economy, Japan has not been a proactive global leader when it comes to crisis management. Its response to the 2008 global financial crisis was a far cry from that to the 1997 crisis, when it took center stage and proposed the creation of a regional monetary fund, a limited version of which materialized eventually within the Chiang Mai Initiative.

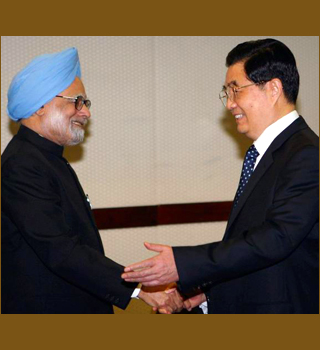

In 2005, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh asserted that “the 21st century will be an Indian century.” Singh expressed hope that “The world will once again look at us with regard and respect, not just for the economic progress we make but for the democratic values we cherish and uphold and the principles of pluralism and inclusiveness we have come to represent which is India’s heritage as a centuries old culture and civilization.” In this ambition, India was praised by US presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, the latter describing India as “a leader in Asia and around the world” and as “a rising power and a responsible global power.”

Yet, the Indian foreign-policy worldview has shifted in the direction of greater realpolitik. Some Indian analysts such as C. Raja Mohan have pointed out that India might be reverting from Gandhi and Nehru to George Curzon, the British governor-general of India in the early 20th century. Curzonian geopolitics assumed Indian centrality in the Asian heartland, and envisaged a proactive and expansive Indian diplomatic and military role in stabilizing Asia as a whole. Indian power projection in both western and eastern Indian Ocean waters is growing, thereby pursuing a Mahanian approach for dominance of the maritime sphere, named after US Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, rather than a Nehruvian approach. It is partly driven by a desire, encouraged by the US and Southeast Asian countries, to assume the role of a regional balancer vis-à-vis China. Like Japan, India has sought a permanent seat in the UN Security Council, a dream likely destined to remain unfulfilled for some time. India has engaged in the G-20 forum, but has not presented obvious Indian ideas or imprints to inspire reform and restructuring of the global multilateral order.

Asia’s role in global governance cannot be delinked from the question: Who leads Asia? After World War II, India was seen as an Asia leader by many of its neighbors and was more than willing to lead, but unable to do so due to a lack of resources. Japan’s case was exactly the opposite; it had the resources from the mid-1960s onwards, but not the legitimacy – thanks to memories of imperialism for which it was deemed insufficiently apologetic by its neighbors. China has had neither the resources nor the legitimacy, since the communist takeover, nor the political will, at the onset of the reform era to be Asia’s leader.

In Asia today, although Japan, China and India now have the resources, they still suffer from a deficit of regional legitimacy. This might be partly a legacy of the past – Japanese wartime role, Chinese subversion and Indian diplomatic highhandedness. But their mutual rivalry also prevents the Asian powers from assuming regional leadership singly or collectively.

Hence, regional leadership rests with a group of the region’s weaker states: ASEAN. While ASEAN is an useful and influential voice in regional affairs, its ability to manage Asia – home to three of the world’s four largest economies; four, excluding Russia, of the eight nuclear weapon states; and the fastest growing military forces – is by no means assured.

Greater engagement with regional forums is useful for the Asian powers to prepare for a more robust role in global governance. So many of the global problems – climate change, energy, pandemics, illegal migration and more – have Asian roots. By jointly managing them at the regional level, Asian powers can limit their rivalries, secure neighbors’ support, and gain expertise that could facilitate a substantive contribution to global governance from a position of leadership and strength.

The author is the UNESCO chair in Transnational Challenges and Governance at American University and a senior fellow of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. This is based on his article, “Can Asia Lead: Power Ambitions and Global Governance in the 21st Century,” International Affairs, vol.87, no.4, 2011.