Can Corporations Safeguard Labor and Human Rights?

Can Corporations Safeguard Labor and Human Rights?

WASHINGTON: A common criticism of free trade is that it fattens the coffers of multinationals, while trampling on the rights and livelihoods of workers, local small producers, and indigenous populations. Though multinationals gain no explicit rights under trade agreements, they have clearly benefited from the economies of scale reaped through 56 years of multilateral trade liberalization. Should multinationals be asked to take on certain responsibilities in return for such trade benefits?

Increasingly, Americans purchase goods manufactured in countries where human rights and labor rights are inadequately protected. Thus, it is important that trade agreements not only encourage trade, but also help developing countries safeguard those rights. In the last 20 years, policymakers have devised a wide range of strategies to address this problem. For example, they have attached side agreements on labor and the environment to NAFTA and funded projects to train developing country officials in how to regulate the environment and the workplace. The jury is still out on these strategies, but they have not completely allayed fears that corporations are leading us on a race to the bottom, where deregulation and noncompliance are the norms.

Policymakers could complement these approaches with a new approach that links trade agreements or trade policies to voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. CSR can be defined as achieving commercial success while valuing people, communities, and the natural environment. There are many different ways companies can put CSR initiatives into practice. Companies can adopt corporate or sectoral codes of conduct or disclosure mechanisms that provide information to investors on the companies’ social and environmental practices. They can also implement certifications or audits by civil society groups or firms hired to assess these social and environmental practices and ensure they are humane and sustainable. In an April poll of 1,000 US business leaders, Wirthlin Worldwide found 92 percent of those polled believe that CSR practices are an "important" component of business strategy, while 62 percent said they are "very important".

Still, it will not be easy to link voluntary CSR initiatives and trade agreements. CSR initiatives are soft law, whereas trade agreements are key elements of international law that regulate the behavior of governments. Policymakers must find ways to link CSR initiatives and trade agreements without violating a key principle of the WTO regime—most favored nation (MFN) treatment. Under MFN, the 148 members of the WTO are required to treat all nations the same. Nonetheless, the US, which is home to a large number of the world's biggest corporations, can easily develop such links within free trade agreements, with non-WTO members such as Russia, or in systems outside the WTO regime such as developing country preference programs.

In the US and other countries where transnational corporations are based, government officials are beginning to link voluntary CSR initiatives to trade policies and to trade agreements. For example, the Dutch government requires all of its firms that want access to taxpayer-subsidized export credits to state they adhere to OECD Guidelines on CSR practices. The Guidelines are recommendations by governments to multinational enterprises addressing business conduct in employment, human rights, the environment, and technology. Some 38 nations, including the US, adhere to the Guidelines. The European Union promotes the OECD Guidelines and calls on its firms to adhere to them in its bilateral agreements.

The Bush Administration has also included CSR language in its bilateral trade agreements (e.g. Chile, Singapore and CAFTA), but it has not specified any particular CSR strategy. It has left it to each company’s management and stakeholders to decide how and whether to promote CSR. But this language appears only in the environmental chapters of these Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). In future iterations, this language should be made more specific and it should be repeated in the FTA’s labor chapter. In addition, the language on transparent rule making could be strengthened to encourage companies to voluntarily disclose information about their overseas social and environmental practices.

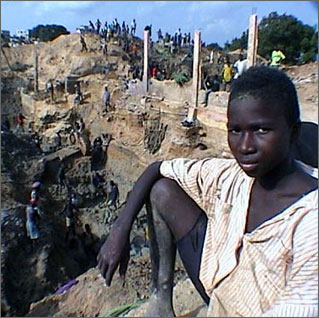

The Administration has also supported the first explicit link of a voluntary CSR initiative (a certification that human rights were not abused in the production of diamonds) to a trade waiver under the WTO. US support of this international endeavor is crucial because the US is the world’s largest market for diamonds. After the UN identified allegations of corporate complicity in human rights violations related to diamond production, the diamond industry developed an industry-wide certification designed to ensure that diamond trade would not fuel conflicts and human rights violations in the mining or production of diamonds. In 2002, the Administration pressured Congress to pass legislation allowing the US to participate in this waiver. According to the South African government, this certification scheme has taught some African governments the importance of monitoring human rights if they wish to export key products.

The Bush Administration should do more. First, they should encourage companies to adopt the most widely accepted CSR initiatives and to build their codes or CSR strategies on these initiatives. These include the OECD Guidelines, the UN-supported Global Reporting Initiative (guidelines for reporting on the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of multinational corporations), and the International Labor Organization (ILO) Declaration (a voluntary code of conduct relating to the labor and social aspects of multinational corporations).

Secondly, the US should be open to other instances where a waiver from WTO obligations may be useful to prevent trade built on conflict and human rights violations. Such instances are rare, but they do happen.

Third, US policymakers may find a link between CSR initiatives and trade particularly useful in China. As China is a WTO member, the US can’t develop CSR strategies that violate the most favored nation treatment. In April, the US-China Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade set up a new working group to examine policy issues that arise as China moves from a planned to a market economy. The two nations also announced a new labor rights dialogue aimed at helping China implement ILO core labor standards. The US could urge its allies and fellow investing nations to press their multinationals to adhere to the ILO Declaration in China. They could ask US companies to help their suppliers adhere to Chinese labor law by posting Chinese labor law in their factories. These companies should also require that their suppliers hold discussions with their workers about their rights under Chinese labor law. Several US companies already do this.

In these times, when America’s credibility on human rights has been seriously damaged during the conduct of its war on terror, it is important that Bush Administration officials do everything they can to promote human rights in other areas. As American corporations are key agents of globalization, ensuring that they act responsibly would be a step forward.

Susan Ariel Aaronson is Senior Fellow and Director of Globalization Studies at the Kenan Institute, Kenan Flagler Business School, University of North Carolina.