Capitalist Democracy’s Left-Behinds Challenge the System

Capitalist Democracy’s Left-Behinds Challenge the System

LONDON: Over the past quarter century Western democratic capitalism has flourished, been tested and is found wanting in a hyper-connected world. Global credibility is already shredded from the Iraq invasion, the Arab Spring and numerous exported democratic blueprints that haven’t worked such as in South Sudan.

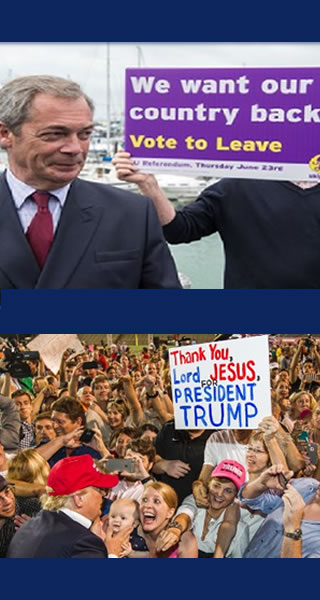

But now there is rebellion in the West itself caused by faltering globalized economies, growing disparities of wealth and a political class perceived as being out of touch, privileged and ineffective. Britain’s decision to leave the European Union and the phenomenal rise of US presidential candidate Donald Trump are two leading examples of this revolt. That they unfold simultaneously is no coincidence.

The concept of the Western-style democratic system is that an accountable government funded by revenue from the market will distribute wealth thus creating a stable society.

After the fall of the Soviet Union it was widely assumed that a progressing democracy, with rival systems defeated, would be the beacon towards which the world would head and how eventually most would live. That is no longer the case. Too many are living fruitful lives under Chinese-led authoritarianism while discontent in the West has created a critical mass of voters convinced that their system is rigged against them.

One of the key pillars of democracy, the partnership between government and citizens in choosing a way forward, is so badly frayed that voters are becoming seduced by authoritarianism and the concept of the strong leader which is a high-risk option for change. They no longer believe that reform can come from those currently controlling the established levers of power. Trump declared in his acceptance of the Republican nomination before an adoring audience, “I alone can fix it.”

The situation is far from comparable to the late 20th century weakening of Soviet-led communism, but there are too many similarities to be ignored.

The democratic ideal itself is not at fault. But the outdated mechanisms through which it is implemented are proving unfit for the modern age. Rather than feeling more involved through their elected representatives, people have a sense of being excluded politically and left behind, economically and this is not how democracy is meant to work.

In both the United States and Britain the views of voters run contrary to those of elected representatives. Almost all Republican members of the US Congress have been opposed to Donald Trump. Yet the Republican presidential nominee crushed 16 rivals including leading establishment figures to win the nomination.

In Britain, more than two thirds of the elected members of parliament chose to stay in the European Union, whereas 52 percent of voters wanted to exit the union in a decision that’s become known as Brexit.

The gap between politician and voter reflects a growing mistrust in government. The Pew Research Center has found that just 19 percent of Americans trust their government compared to more than 70 percent in the 1960s.

The Edelman Trust Barometer in Britain shows how confidence in government increases with wealth. Among those earning more than $150,000 a year, trust runs at more than 50 percent. But in the low-income bracket of those earning less than $20,000 a year, some 75 percent have little or no trust in government.

This trust deficit is producing a new style of politics in which the economy and living standards take second place to the restoration of dignity. If material gain needs to be forfeited, then so be it.

In Trump's case, it’s about “taking back America” from the internationalist establishment. In Britain, experts’ warnings against job losses and a fall in living standards counted for little against the belief that Britain was regaining “independence” from Europe. As anti-EU campaigner Michael Gove said bluntly: “People have had enough of experts. They want to take back control.”

A side effect of this is that details, facts and truth have taken a back place to personal sentiment. Both the Trump and Brexit campaigns have been popularized on a stream of misinformation.

Trump’s claims are regularly fact-checked as incorrect, such as saying that America is the highest taxed country in the world when PolitiFact found that it lays far down the table after countries like Denmark and France. PolitiFact’s scorecard has detected that more misinformation comes from Trump while Hillary Clinton stands at the truth-telling end of the chart.

Yet, for months, Clinton has only been a fraction ahead of Trump in the polls.

Within hours of winning the vote in Britain, Brexit campaigners were back-tracking on claims that money would be saved and immigration numbers that would be cut. Lead advocate Boris Johnson, former mayor of London, has long been accused of lying and misleading the electorate about the European Union, yet has been rewarded with the prestigious job of foreign secretary and remains one of Britain’s most popular politicians.”

“In a post-factual political age, reasoning doesn’t reach the heart,” Canadian High Commissioner to Britain Jeremy Kinsman advised in a letter to outgoing Prime Minister David Cameron. “To win, you needed to mobilize convincing passion.”

Not only passion is needed, however, but also aggression. Popularity of both Brexit and Trump has been gained on fear rather than optimism.

Brexit’s Johnson compared the EU to Hitler’s Germany in its quest to create an undemocratic super-state. He and his colleagues painted a picture of Britain as impoverished and angry, controlled by foreign powers and swamped by migrants. Yet Britain has its lowest unemployment ever and during the campaign was set to become Europe’s best performing economy.

In a similar vein, Trump painted America as dark, a broken nation, prompting a measured response from President Barack Obama that this was not the nation he recognized. “We’re not going to make good decisions based on fears that are not based on facts,” he said.

If Western democracy is moving towards fear-driven politics, the dangers are acute as a key tendency is to blame others for society’s ills. Sometimes the target is “the other” – an ethnic or religious community – sometimes a concept such globalization that’s now being condemned by so many and sometimes it’s an unpopular overarching authority. We have seen what happens when that authority is unglued. Former Yugoslavia disintegrated into civil war when Soviet influence vanished, and Iraq followed a similar path with the ouster of Saddam Hussein.

It’s notable that Britain is dealing with an upsurge of ethnic hate crimes after the Brexit vote, and Scotland said it would plan another referendum to separate from the United Kingdom.

Western democratic institutions should be strong enough to withstand the worst of these pressures, but the question still must be asked as to what would Trump focus his hostility on should he succeed against his current target, Hillary Clinton, and where will British anger wander after the country leaves the EU.

Britain’s new Prime Minister Theresa May has been catapulted to office on the back of this widespread dissatisfaction, which she acknowledged in her first speech. “When we pass new laws we will listen not to the mighty, but to you,” she promised. “We will make Britain a country that works not for a privileged few but for every one of us.”

For the penny to drop, however, it has taken the imminent disintegration of the world’s biggest trading bloc and the placing of a bombastic television celebrity real estate mogul within a hair’s breadth of the White House.

The pillars of democratic capitalism urgently need to be repaired and reformed. It is no longer the only show in town, and a rival system selling the vision of a wealth-creating, infrastructure building, high-achieving, hard-driving one-party state is now snapping at its heels.

Humphrey Hawksley, a former BBC Beijing bureau chief, is the author of Democracy Kills: What’s So Good About Having the Vote? His new book Asian Waters is due out in 2017.