Chávez-China Oil Deal May Produce Unsuspected Winners

Chávez-China Oil Deal May Produce Unsuspected Winners

NEW YORK AND CARACAS: Hugo Chávez ended his recent visit to Beijing with an announcement that he intends to dramatically increase oil exports from his country to China in the years ahead. This was followed by a statement from Chávez’s energy minister that Chinese firms plan to invest $5 billion in Venezuela’s oil sector. As Venezuela is a major supplier of oil to the US, these events likely raised the eyebrows of those in Washington concerned with the impact of China’s growing oil demand. Yet a closer look at the agreements signed in Beijing reveals little cause for alarm. In fact, Chinese investment in Venezuela could prove beneficial for US energy security.

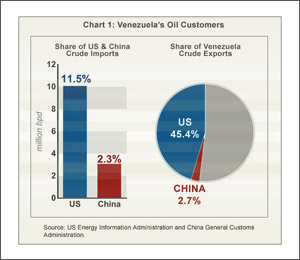

With 2.6 million barrels-per-day (bpd) of crude production, Venezuela ranks as the world’s 12th largest oil supplier. Nearly half is sold to the US market, where refineries are optimized to handle the heavy, high-sulfur crude produced by state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), as shown in Chart 1. In comparison, Venezuelan exports to China, while growing, account for less than 3 percent of both Chinese demand and Venezuelan output.

Despite relatively large proven reserves, Venezuelan production has fallen over the past seven years, primarily due to the politicization of the country’s oil sector and upheaval inside PDVSA which resulted in the firing of 18,000 employees in 2003. As Venezuela is the fourth largest supplier of crude oil for the US after Canada, Mexico and Saudi Arabia, Washington is sensitive to rhetoric from Caracas that raises the prospect of any reduction in supply. For this reason, President Hugo Chávez’s goal of increasing Venezuelan oil exports to China from less than 100,000 bpd today to 500,000 bpd by 2009 and 1 million bpd by 2012 garnered considerable attention. With most analysts projecting relatively flat Venezuelan production of conventional crude in the years ahead, such an increase in exports to China could imply redirecting oil previously bound for the US. Yet, even if that was the intent, China lacks ability to refine Venezuelan crude.

Until 1993, China was a net exporter of oil. The low-sulfur crude from China’s Daqing and Shengli fields not only satisfied domestic demand, but were also sold to Japan and Korea. As these fields matured and the domestic economy heated up, China’s oil position reversed. Today, China imports more than 40 percent of the oil it consumes. This rapid import growth has left China’s refiners struggling to retool for the types of oil available in the international market.

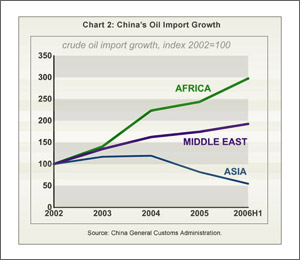

Most Asian and African crudes match closely, in terms of weight and sulfur content, with China’s domestic oil, and thus the existing refinery infrastructure. Oil from Sudan and Nigeria serve as perfect substitutes for Daqing crude, Angolan oil has characteristics similar to that from Shengli. While China has sought to upgrade its refining infrastructure to handle the high-sulfur oil from the Middle East, high growth rates and undercapitalization resulting from retail price controls have hampered progress. As a result China relies more on Africa and less on the Persian Gulf than its neighbors in Northeast Asia, as shown in Chart 2.

Year-to-date, China has imported 69,000 bpd from Venezuela (compared to 478,000 bpd from Saudi Arabia), much of which has been traded in Singapore for more suitable crudes. Increasing that trickle of supply to 500,000 bpd by 2009, as President Chávez called for, would require immediate construction of Venezuelan-optimized refining capacity in China. Equaling 23 percent of the marginal increase in China’s oil imports over that period, Venezuelan oil would compete with Middle Eastern crudes for the same limited high-sulfur refining capacity. While Kuwait and Saudi Arabia actively seek to construct refineries to process their respective crudes, none of the currently planned capacity focuses on Venezuelan oil. Caracas is certainly aware of these market constraints. In fact, the nature of the deals proposed suggests that the real intent is not to redirect conventional crude from the US to China, but to attract Chinese investment for the production of syncrude.

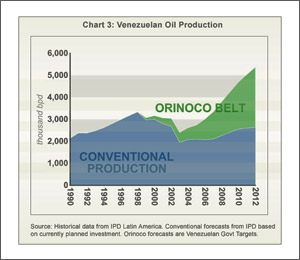

In addition to Venezuela’s proven conventional reserves of 80 billion barrels, an area known as the Orinoco Belt contains more than 230 billion barrels of extra-heavy tar-like oil, the equivalent of 20 percent of current global proven reserves. Over the past five years, upgrading this extra-heavy oil into a syncrude that is lower in sulfur and can be handled by traditional refineries has made up for some of the decline in conventional Venezuelan production, as shown in Chart 3. Venezuela hopes to expand syncrude production by 2 million bpd over the next six years, which requires at least $40 billion in investment. Chávez would like much of that to come from China. And with mature domestic production and loss-making refining segments due to retail price controls, Chinese oil majors such as CNPC (parent of publicly listed PetroChina) and Sinopec are eager to improve profitability by investing in upstream production. If the Chinese majors choose Venezuela for some of that investment, the political plus for Chávez does not necessarily translate into an economic minus for the US.

The notion that production agreements signed by CNPC and Sinopec outside China somehow reduce the amount of oil available to the rest of the world belies a misunderstanding of the nature of both oil markets and Chinese oil companies. Oil is a global, fungible commodity. This year China will consume 500,000 bpd more than it did in 2005. In 2007 demand is likely to grow by another 500,000 bpd. That oil, used to make gasoline for Buicks, plastics for toys or chemicals for industry, must come from somewhere. Currently, most comes from West Africa and the Persian Gulf, where tight capacity helps push up oil prices worldwide, or from Sudan and Iran, where Chinese investment creates human rights and national-security challenges for the West. The Orinoco Belt, with reserves equal to Saudi Arabia’s, has the potential to go a long way toward meeting marginal Chinese demand, thus taking the pressure off Middle East and African crude and lowering prices for everyone. Each barrel China buys from Venezuela is one less it needs to buy from Iran.

Despite winning Chávez’s favor, Chinese oil companies are unlikely to succeed in extra-heavy oil extraction and upgrading endeavors undertaken in exclusive partnerships with PDVSA. CNPC does not have the technology or experience to meet the Venezuelan government’s increased recovery-rate targets or heavy oil-processing goals. The technical hurdles CNPC faces in accepting Chávez’s invitation create real opportunities for cooperation between CNPC and the international oil companies interested in staying in the country, many of whom already produce Orinoco syncrude. Coupling that technical prowess with CNPC’s political capital in Caracas could result in a project that gets a regulatory green light, financing and the expertise to succeed.

Such a partnership would serve both US and Chinese interests. Chinese oil majors would improve their balance sheet by expanding their upstream production assets. Exposure to western corporate culture and management techniques would help CNPC become more like a “normal” international oil company, willing to play by internationally accepted norms, and less like an arm of the Chinese government. Oil that might have gone undeveloped without Chinese involvement would be delivered to global markets, and US and European firms would have a stake in future Venezuelan production.

Trevor Houser is an energy analyst with China Strategic Advisory; Daniel Rosen is principal with China Strategic Advisory and a visiting fellow with the Institute for International Economics; and David Voght is managing director with IPD Latin America.