Childless by Choice

Childless by Choice

NEW YORK: While considerable media attention has focused on the world’s population reaching the milestone of 7 billion, another demographic phenomenon receives little notice: the rise in number of people who choose not to have children. Against a birthrate of less than two children per woman in nearly all Western countries and a growing number of developing countries – a rate that assures a decline in population – rising voluntary childlessness will have consequences for government programs for the aged, undesirable implications for the elderly and other repercussions, including smaller cohorts of children, increased population aging and demographic imbalances among educational groups.

When early marriage is close to universal and birth control is practiced little, less than 3 percent of women remain childless by the time they reach their late 40s. Until the early 1960s and the introduction of reliable family planning methods – namely, the oral contraceptive pill – childlessness within marriage was almost entirely involuntary.

The modern era provided more education opportunities for women, leading to later marriage, careers, lower proportions marrying, greater use of contraception and abortion, and changes in women’s role and status. As a result, the proportions of childless women in developed countries and many developing countries are well above 3 percent.

Increasing numbers of women attend schools and universities, pursuing employment, career development and self-enrichment. Consequently, women start childbearing later in life than they did in the past. Among OECD countries, for example, between 1970 and 2008 the average age at which women had their first child increased from 24 to 28 years. In Germany, Italy and Switzerland, the average age of first childbirth of women is higher, approaching 30 years. As a result of delayed childbearing, older women may find it difficult to become pregnant.

Childlessness rates are strongly connected to women’s educational levels. Women with university education, for example, are more likely to be childless than those with secondary education. In addition, young women who are highly educated are more likely to choose employment and postpone family building. Another contributing factor to higher rates of childlessness among highly educated women is their reluctance to marry a less educated man.

By and large, women, especially those highly educated and seeking gender equality, have more to lose in terms of employment, careers and related opportunity costs than men when they become parents.

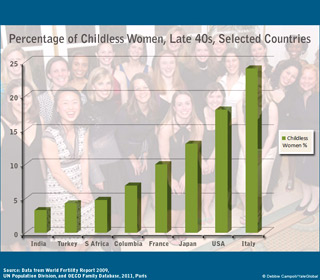

In most of the less developed countries the percentage of childless women in their late 40s is typically under 10 percent. And in some populous nations, such India, Indonesia, Pakistan, South Africa and Turkey, the proportion of women remaining childless by their late 40s is below 5 percent. In contrast, in the majority of developed countries childlessness among women at the end of their reproductive careers is above 10 percent. In some countries, such as England, Germany, the Netherlands and the United States, the proportions are substantial, with approximately one in five women in their late 40s remaining childless. Higher proportions are observed in Italy and Switzerland, where one in four women in their late 40s is childless.

In Australia, Germany, Italy and the US, the proportion of childlessness among women in their late 40s has doubled over the past three decades.

Government policies can influence the childbearing rate. Maternity and paternity leave, childcare, part-time employment, job security, cash allowances, tax credits and other financial incentives are among the measures to encourage childbearing. Punitive polices are also tried like prohibiting abortion or contraception and restricting girls’ education and women’s employment.

Providing tangible support to couples is an especially critical factor influencing childbearing decisions. For example, in France, where the childlessness rate is around 10 percent, government policies and programs, including maternity/paternity leave, nurseries, afterschool programs and child allowances, facilitate family building and women’s participation in the workforce.

With a childless level similar to France, but a lower birth rate, Russia is considering pronatalist policies, such as financial support to families with three or more children and free land plots, raising student scholarships and reducing real estate costs. More desperate measures to encourage childbearing are also proposed, including reinstating a childless tax that existed in the Soviet Union between 1941 and 1992, whereby childless men aged 25 to 50 and women aged 20 to 45 paid an extra 6 percent of their monthly salaries to the government. Other low-fertility countries, such as the Ukraine and Germany, also debate a special tax on men and women who remain childless by choice.

Childlessness is often not a clear lifestyle choice – that is, women deliberately pursuing individual satisfaction and rejecting childrearing responsibilities. Most remain childless after a series of childbearing postponements, including higher education, employment, absence of a suitable partner, separation or divorce. In the US, young single, childless women now earn more than male counterparts, attributable to the higher education attainment, and this may account for women’s difficulties in finding a suitable partner.

Men and women, especially in more developed countries, are also becoming more realistic about their expectations of family building, recognizing that many marriages end in separation and divorce. The cultural pressures to marry and have children are considerably less than they were in the past, while remaining childless is increasingly viewed as a viable lifestyle option.

Historically, childlessness was a rare occurrence and had limited demographic consequences at a time when most families were large. Today, with smaller families, the demographic impact of childlessness is more consequential.

In the US, for example, the percentage of women in their 40s with three or more children fell from 59 percent in 1976 to 29 percent in 2010. In Italy, a nation with a tradition of large families, the percentage of women in their 40s with four or more children dropped from around 17 percent in the early 1980s to less than 5 today.

Voluntary childlessness contributes to keeping fertility below the replacement level – on average about two children per woman – which reduces the size of the future labor force, boosts the proportions of elderly and thereby increases old-age dependency ratios. In turn, this can lead to more program support for the elderly, less support for education funding and other community programs for children. These demographic changes have far-reaching implications, especially with regard to the domestic labor force, immigration levels, voting patterns, taxation, pension expenditures, education funding and health-care costs.

Recent evidence suggests that aged childless couples, especially women, are likely to be disproportionately affected. In Italy, studies have found that older non-parents lacked the health care and social support that adult children and professional caregivers could provide. Similarly, in the US, based on the experiences of several states, childless older adults were likely to have higher medical costs and more complex health-care needs than older couples with children.

The population of childless aged couples, especially women, is expected to grow rapidly. In Italy and the US, for example, the population of childless women aged 65 or older is expected to nearly quadruple over the next four decades. These projections raise questions about the provision of care for childless women and men upon reaching advanced ages.

With the decline in large families and upswing in childlessness, the low fertility rates in many developed countries are unlikely to rebound to replacement levels anytime soon, especially given relatively high levels of youth unemployment, the continuing economic recession and gloomy prospects for a rapid, painless recovery.

The current severe budget deficits facing many developed countries and acrimonious negotiations on the future of the welfare state will likely result in reduced government entitlements, especially for older persons. A vivid example was the recent axing of the newly approved US long-term insurance program even before it was implemented.

Given the anticipated substantial cutbacks in entitlements –already underway in European nations – it’s doubtful that governments can provide sufficient financial and human resources to care for the growing numbers of elderly without children.

Joseph Chamie is the former director of the United Nations Population Division and Barry Mirkin is an independent consultant.

Comments

....good except any info from Ireland and Malta, the only two West European countries that didn't legalize abortion and Ireland only decades later after other developed countries legalized contraception for married couples and in 1995 fault based civil divorce. Any info from Poland, a more traditional country than most ?

Children are actually a family's and a nations future.

Childless women, not men, are the reason for the problem of shrinking native populations. Upon attaining the age of consent women who have no children or are not pregnant should be compelled to pay a heavy tax.

Unmarried women who have no children should be taxed double the rate for married women who have no children.

Early abortion should have a punitive tax. Abortion of fully formed fetuses should have a severe prison sentence laid upon the mother. Abortionists should be sent to prison for life without possibility of parole.

Women who bear more than a certain number of children should not be taxed, instead they should be awarded a subsidy. Women who do not want children but bear them may put them up for adoption. They will be taxed or subsidized at half the rate of women who bear and raise children.

Many details will have to be worked out.

In response to Harry. Women have forever been coerced into doing all the tasks of childrearing by themselves and have then been demeaned for doing this work. No more. Another system with coorperative methods of childrearing between men and women must be developed. What you suggest is abhorent.

In a highly populated country like India, a large section of women give birth to more than two children. The children are born accidentally or incidentally as by product of fulfilling sexual desire of the partners ( unprotected sex) . This happens to the section of a population where education and income are very low. Most of the mothers are anaemic and they give birth to underweight and malnourished children. Those children grow malnourished as the parents cant afford to provide nutritive food. This creates a vicious cycle of generations of physiaclly and mentally weak population, which in turn become a huge burden instead of being asset of the country.