China Joins the Global Economy - Part One

China Joins the Global Economy - Part One

HONG KONG: China's rise from an isolated giant to one of the world's fastest growing economies and a poster-child of globalization is a well-known story. But how China's commissar achieved this feat bears retelling.

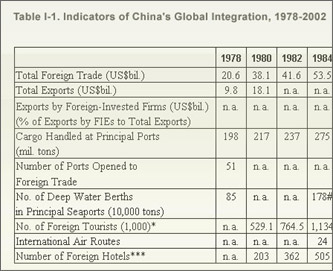

China's economy in 1978 was highly regulated, firmly in the clutches of bureaucrats in the Chinese Communist Party. It was also very isolated. China's total foreign trade in 1978 was only US$20 billion, making it an insignificant player in world trade. Only half a million tourists visited the country that year, and they found themselves ensconced, not in luxury hotels, but in Spartan, Soviet-style guesthouses built during the 1950s. Between 1978 and 2002, however, transnational exchanges boomed (see Table I). By 2002, the amount of goods passing though Chinese ports had increased almost ten-fold, while the number of tourists had leapt to over 10 million.

How did China do it? How did this isolated, communist-run country with a command economy develop such intense global links in such a short period of time? And, did Communist Party officials and bureaucrats help or hinder this process? Many factors lie behind the remarkable transition. However, self-interested bureaucrats, mainly at the local level, played the key role. The more they opened the economy, the more they gained - "no flow, no dough" - and so they facilitated China's opening.

The country's central leaders were the first of the four factors that led to China's global integration. Only they could undermine Maoist justifications for autarky and overcome political resistance to liberalization. When the late Deng Xiaoping took his famous "Southern Tour" of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone in January 1992, he called on local officials to "move faster and be bolder." His words gave them the green light to open the economy to internationalization and market exchanges.

The second factor that fueled China's success was the country's immense comparative advantage. Significant differences in the value of goods and services inside and outside China, created by decades of economic autarky and cheap labor, meant that those who could move goods, services, technology or themselves across China's borders could earn large profits in either the domestic or international market. For example, while a professor in China earned about US$1,500 a year in 1991, remuneration at an American university might have been US$40,000 for the same courses. Little wonder professors pushed their universities to establish more academic exchanges.

Similarly, many foreign products faced limited competition in Chinese markets and could earn what economists call "extra-normal profits." Local government officials regulated these imports and harbored close relationships with China's businessmen overseas. They were therefore able to ensure themselves a piece of the profit, which gave them an incentive to be helpful.

Thus, these bureaucrats emerged as a third facilitator of China's internationalization. Hoping to control the process, the central government used various administrative units and legal institutions to create what I call 'channels of global transaction', empowering bureaucrats as gate-keepers of the state's global commerce. All foreign aid donors, for example, had to work through bureaucratic offices and educational exchanges were handled by "foreign affairs" offices in universities. But bureaucrats had few incentives to block exchanges. Facilitating flows, not stopping them - or what I call "no flow, no dough" - was the better, more profitable, strategy. And, as Beijing decentralized control over many of these channels during the 1980s, these bureaucrats were able to proceed, largely unsupervised.

Finally, government policy created incentives for local organizations and governments to link globally. Under tax reforms in the 1980s, localities were required to send a set amount of taxes to the next administrative level. However, any above-quota taxes stayed with the local government, giving them strong incentives to seek profitable transnational linkages. Because openings to the global economy were always followed by periods of retrenchment, each time the state eased its transnational controls, domestic actors feverishly sought global exchanges and established more channels than the central leaders had desired.

These four factors consistently conspired to advance internationalization throughout China. However, the way they manifested themselves varied depending on the distinct characteristics of the region and, specifically, on whether the area was rural or urban.

In some cities, China's leaders attempted to control the global opening by adopting a strategy of 'segmented deregulation.' Under this policy, the central government opened various regions to foreign exchanges by declaring them 'special economic zones,' 'open coastal cities,' or export processing or high tech zones. These open areas were granted preferential policies - lower taxes for foreign and domestic investors, export/import powers, and freedom to raise capital, etc. - which cut transaction costs and improved their comparative advantage. Yet, while the central administration facilitated the opening of these localities, other areas remained tightly regulated or completely closed.

Deregulated cities, however, seized the opportunity to link globally and quickly attracted both domestic and foreign investors. The success of these opened cities did not go unnoticed in other areas. Indeed, after Beijing announced in 1990 that it would invest RMB10 billion (about US$1.2 billion) in Shanghai's Pudong district - China's newest special zone - cities nationwide suddenly established their own zones and lobbied furiously to have them declared national-level export or high tech zones, with all the accoutrements of official preferential policies. By 1992 and Deng's southern tour, 'zone fever' was sweeping China. Within a year, over 8,000 zones of various kinds offered foreign and domestic investors exemptions from government taxes that they technically lacked the power to grant, but that nevertheless propelled the pace of internationalization.

Similarly, in 1987, then-premier Zhao Ziyang, hoping to use rural China's cheaper labor to promote his export-led growth strategy, opened rural industries to exports and foreign investors. The channels of global transactions were joint ventures (JVs), owned by both foreign and Chinese investors and supervised by local foreign trade officials. Joint ventures that exported the majority of their products (70 percent) had their revenues taxed at the preferential rate of 15 percent, as opposed to the standard 55 percent rate on domestic enterprises.

In the countryside, joint ventures allowed rural factories to circumvent the state's foreign trade monopoly and establish direct access to foreign markets. Also, foreign technology helped JVs create products that were in short supply domestically and could earn high profits. Local governments, which owned the rural enterprises, were also partners in the JV and shared in those profits. So, after Deng's 1992 southern trip, a 'joint venture fever' swept rural China.

Although the first round of opening was successful, the domestic interests that drove the first stage do not necessarily favor further opening. The proliferation of transnational exchanges during the last 20 years has created a bureaucrat's paradise, allowing officials to maximize their incomes and power. Most still want to keep their 'power of approval' and resist further deregulation. And, in their heart of hearts, many central leaders still believe that the state should direct China's search for wealth and power. However, by joining the WTO and subjecting China to international rules, China's leaders are exposing recalcitrant bureaucrats to external pressure. Using the rules of the WTO, the international community will hopefully be able to break the stronghold local officials have on trade policies and thus continue the opening of China.

David Zweig is a professor in the Division of Social Science at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. His most recent book is “Internationalizing China: Domestic Interests and Global Linkages”, from Cornell University Press.