China Joins the Global Economy - Part Two

China Joins the Global Economy - Part Two

Twenty years ago, 80% of the Chinese population survived on less than a dollar a day. Rural families saved for a year to buy a pair of rubber boots, and urban families needed ration coupons to purchase cooking oil, sugar, and coal. Today, rationing has disappeared, and consumer goods that once were luxuries for the elite are now routine purchases. In 2002 more than half of rural families owned a color television, while 230 million mobile phone accounts have made China Motorola's number one market. Millions of Chinese own private cars, and university students routinely turn to the Internet for international news and stock prices. But questions arise - particularly in this period of global economic slow down - about the sustainability of the "good news" from China.

Looking at the basic trends in China's age ratios, education, and health care, I expect continuing gains in terms of standard of living and human capital investments. In short, when sociologists looks at China today, we see a country with substantial 'software advantages' that promise to sustain growth and create greater prosperity.

Although some economists - like Thomas Rawski of the University of Pittsburgh - have raised appropriate questions about inflated growth rates and unproductive investments, most experts studying macro-level change worry less about inflated growth rates and more about the widening gap between the affluence of coastal cities and the hardscrabble life of the rural majority. Between 1988 and 1995 China experienced the most rapid increase in income inequality of any country ever tracked by the World Bank. Per capita urban incomes were 2.2 times higher than those of rural households in 1990. By 1999 the ratio had risen to 2.6, and just one year later to 2.8. Moreover, when one adjusts these ratios for higher tax burdens in rural areas and higher subsidies given urban residents for housing, medicine, and education, average urban incomes are actually more than four times as high as average rural incomes. The result is that the gap between China's rich and poor is now comparable to that of the Philippines, although significantly less than in Brazil.

Several reasons have been proposed to explain this growing income inequality. They include the deficit of wage jobs outside of agriculture in rural areas and an urban employment system that offers little wage growth to unskilled labor. Rather, workers in urban areas command a premium if they have high tech skills for which there is increasing global competition. Studies have shown that the biggest winners in China's more marketized economy of the 1990s were a minority of men with tertiary education who worked in managerial positions in large coastal cities. The losers were farmers and manual workers in both urban and rural enterprises.

Thus, the growing general prosperity of the Chinese people coincides with growing income inequality. Given this duality, many questions are inevitably emerging about the future of China's economy. In particular, many ask: Will the bubble burst? Will the increasing income gap create a backlash that will drastically slow economic growth?

Based on broader sociological data, I believe, that the answer to these questions is no, at least for the next five years. Even against the somber picture of increasing income inequality, the positive trends of China's improving "human software" remain impressive and promise to be extremely influential in continuing to raise standards of living by raising productivity and creating new, higher skill jobs.

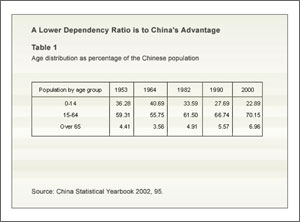

Among developing economies, China has an unprecedented demographic advantage in its low dependency ratio: Between 1990 and 2000, the percent of the population under age 15 and older than 64 slightly declined. (See Table 1). Over the next five years, the overall dependency ratio will remain within this same range. Even if the growing number of elderly places greater demands on medical services, the falling percentage of young children suggests that both local governments and families will maintain or even increase their investment in primary and secondary education. Given the excellent core curriculum across the entire country, China is therefore well positioned to continue to upgrade its "human capital" over the next decade.

Indeed, education in China has already vastly improved, both in comparison to its own experience during the early 1980s and in comparison to countries with large agrarian populations in Latin America, Africa, and South Asia. Illiteracy dropped significantly for both men and women during the second half of the 1990s, falling in 1999 to 8.8 percent for men and 24.5 percent for women. In addition, a higher percentage of teenagers are attending school and graduating. The central government has mandated free education through grade 9 since 1986. As a result, the number of teenagers aged 12 to 14 attending junior high school rose to about 85 percent in 1998, with 80 percent of those who entered graduating. Many of these graduates even went on to higher education. In 1990 about 3.4 percent of those aged 18 to 22 were attending post-secondary schools; by 2000 the percentage reached 11.5. Thus, the government's target of 15 percent by 2004 seems increasingly realistic.

The Chinese population is not only becoming better educated, but healthier as well. Though the world was recently made aware of the economic costs of AIDS and the decline of public health programs as seen during the SARS outbreak, in terms of macro-level trends, China has a health profile of a middle-income country. Moreover, the general health of China's population continues to improve. During the 1990s, life expectancies increased to 68.7 years for men and to 73 for women. China still retains a national health system capable of effective coordination and mass education. Skilled professionals exist in virtually all county hospitals, and a domestic pharmaceutical industry allows China to immunize more than 95 percent of children against the full range of childhood infectious diseases. And it is probable that in response to the SARS outbreak, the central government will invest funds to repair much of the neglect of public health over the past 15 years.

Rising rates of unemployment in the cities and growing inequality threaten long-term growth at societal and household levels. And if the Chinese government fails to mobilize the healthcare system to curb the spread of AIDS, the disease will divert scarce welfare funds from education and infrastructure investments. Such a scenario would undoubtedly undermine the strengths of China's population, and therefore of its growing economy.

However, given the continuing improvements in China's human software, the core fundamentals for macro-economic growth remain strong. In the immediate future, therefore, even with little or no growth in rates of global trade, it is unlikely that China's economy will burst like a bubble.

Deborah Davis is Professor of Sociology at Yale University. A longer version of this article appeared in Asia Program Special Report No. 111, of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, in June 2003.