China Reluctant to Lead

China Reluctant to Lead

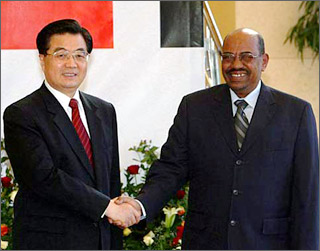

Omar Hassan Ahmed Al-Bashir in 2007, before his arrest was ordered by the International Criminal Court

NEW YORK: On her recent whirlwind trip to Asia, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton seemed not only set on bringing the US out of the global leadership wilderness in which it had fallen, but on bringing China into a whole new relationship with America. By inviting China to form a new partnership, the US has in effect challenged China to emerge from its cautious cocoon of self-reliance and embrace a leadership role befitting its wealth and power and new global reach. How China responds to this invitation in the months to come will have impact not only on its bilateral relations with the US, but on how the global challenges of economic crisis and climate change play out.

The last time the US-China relationship underwent a real paradigm shift was when Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger went to Beijing in 1972 and began the process of diplomatic normalization. The common threat that pulled the two countries together into a united front then was the Soviet Union. Now, Secretary Clinton has cited the collapse of the world economy and menace of climate change as new, potential catalytic agents for cooperation.

Her strategy is to forge an active partnership around areas of common interest which could cushion this most critical of all bilateral relationships, so that the welter of important but intractable other issues that have hitherto bedeviled it – currency exchange, Taiwan, Tibet, human rights, etc. – will not repeatedly derail better relations.

"It is essential that the United States and China have a positive, cooperative relationship," Clinton told the Chinese foreign minister, Yang Jiechi, even going so far as to declare that “Human rights cannot interfere with the global economic crisis, the global climate change crisis and the security crises."

President Hu Jintao concurred by saying, “Now it is more important than any time in the past to deepen and develop China-US relations amid the spreading financial crisis and increasing global challenges."

But Chinese leaders have long insisted that, on climate change, the US, a developed country, had to lead the way. Of course, while they waited for the US, Washington waited for them, and little got done. But, now that Secretary Clinton has started to lead by acknowledging that the US and other developed nations have contributed a far larger historical burden of emissions to the atmosphere and continue to consume per capita an amount that is four to six times that of the average Chinese. By doing so, she has indirectly posed the question: Are the Chinese ready to lead, or, at least, to partner?

In truth, despite its phenomenal rise to the status of the world’s third largest economy, until now, China has not been psychologically prepared to play a full “great power” leadership roll in confronting problems such as climate change, genocide, civil war, nuclear proliferation, much less abusive governments. Its rigid notion of sovereign rights has made leaders reluctant to publicly criticize or overtly intrude into the internal affairs of other countries. This reluctance has only been reinforced by China’s view of itself as a victim of hegemonic predation by colonialist and imperialist stronger powers over the past century and a half. This historical experience of having been humiliated by such intervention has made it unwilling to give any appearance of engaging in such activity itself, much less in seeming to advocate any kind of regime change. After all, if China began intruding on, even censuring, countries like Burma, Sudan, North Korea, Zimbabwe or Iran, would that not be an invitation for other countries to intrude on it?

And so, even as the world globalized and Chinese prospered from it, Beijing remained aloof from shouldering many of the kinds of non-business-related, trans-national responsibilities that have come to characterize the new world scene. Its leaders might sometimes become nationalistic and bellicose, especially when China’s territorial integrity was involved. But, in general, they remained understated, conservative and prudently withdrawn. As Zheng Bijian, former head of the “China Reform Forum,” noted in a 2005 “Foreign Affairs” article, China “doesn’t intend to challenge the existing order, nor will it advocate undermining or overthrowing it…” Foreigners, who are impressed by China’s recent progress, sometimes impute almost superman-like qualities to the Chinese themselves, imagining that a new self-confidence – the opposite of victim culture – must surely accompany such success. But, the truth is that old psychological mindsets and ways of relating to the world have changed far slower than the urban landscape might suggest, leaving China’s self-confidence lagging behind its actual achievements.

As the Obama administration was preparing to take office, I happened to be in Beijing. When the subject of future US-China relations arose in discussions with people of influence, I was surprised by how hesitant, even supine, they were. That they cared deeply what happened was self-evident. But, rather than feeling called to the challenge of actively influencing the very interactive process of policy formulation by speaking up, writing and making suggestions, they remained notably reserved and passive. Rather than asking what they could do to influence the situation in a pro-active way, they anxiously wondered about who would be appointed in Washington and what policies they would hand down. For all China’s greatness, one had the sense of a China still waiting to be acted upon.

China’s cautiousness and reluctance to write itself larger in the world arena has actually been a positive factor in calming world fears about its “rise.” In this sense, its policy of refusing to take up the laurels of global leadership too ardently has served it well… at least until now.

Tactically China’s reluctance to appear to forward also derives from another deep wellspring, a very pragmatic fund of traditional strategic thinking that stretches back centuries to the “The Seven Military Strategies,” a series of seven classics on military strategic thought, including Sunzi’s famous “The Art of War,” written between 500 BC and 700 AD and first collected during the Sung Dynasty. These classic texts are replete with formulas for winning, but not simply by means of brute, military force, but through indirection, stealth and even deception.

Shortly after the dark days of 1989, China’s supreme leader Deng Xiaoping exemplified this kind of strategic thinking when he urged Chinese to, “Observe developments soberly, maintain our position, meet challenges calmly, hide our capacities, bide our time, remain free of ambitions and never claim leadership.”

Deng was suggesting that as China developed during the difficult post-1989 years, it would fare best if it exercised restraint, avoiding all demonstrations of overt power that might cause fearfulness and counter-reactions among the then deeply suspicious world beyond. And, unlike Mao Zedong, whose various theories claimed leadership in world revolution, leaders since have sensibly sought to restore their country’s wealth and power without alarming countries that China’s rise might potentially displace. Under Deng, China publicly eschewed support for foreign revolutionary organizations and sought cooperation with countries it had earlier condemned as lackeys of imperialism. And, what better way to camouflage China’s ascendancy, than to promote the idea of a “peaceful rise,” also attributable to Zhen Bijian, eschewing grand leadership roles in the world and keeping its figurative head down?

Since Deng issued that directive, China has gained an enormous new quotient of wealth and power and the world has changed dramatically. Moreover, the US at last seems finally ready to approach China as true partner against such common threats as climate change. But, are Chinese leaders now ready to recognize that the real challenge of a great power is not to find ways to eschew a “claim leadership,” but to embrace that claim in ways that are constructive and reassuring to wary neighbors?

The US and China remain divided by many differences, and to date both have been reluctant to fully engage each other. But, if Secretary Clinton’s bold trip to Beijing can catalyze Sino-US relations into a new era of active collaboration on such daunting challenges as climate change, we may yet be able to speak of another paradigm shift. If Chinese leaders continue to feel themselves still unready to begin assuming these new responsibilities, the US, already weakened by eight disastrous years of the Bush administration, will find itself left to act alone. And, as all the world knows, the sound of one hand clapping is silence.

Orville Schell is director of the Center for US-China Relations at the Asia Society and founder of “The Initiative for US-China Cooperation on Energy and Climate Change.”