China Sees Globalization’s Downside – Part II

China Sees Globalization’s Downside – Part II

IRVINE: Since the late 1980s, China’s leaders have embraced globalization in a bid to remake the nation, and it has recently sought to leverage its growing economic power in a grand re-branding exercise. China, the exercise tried to show, was no longer Mao’s backward revolutionary country, but a modern superpower. Unfortunately for China, the same interconnected world that enabled its economic surge has sometimes stymied the nation’s public relations efforts.

The re-branding drive has overlapping, but somewhat different domestic and international ambitions. President Hu Jintao and his comrades strive to convince China’s citizens that they can simultaneously raise living standards, maintain stability and garner international respect. The emphasis abroad, meanwhile, has been on convincing residents of foreign countries, including people of Chinese ancestry, that the People’s Republic of China 2.0, though still run by a Communist Party, has been utterly transformed.

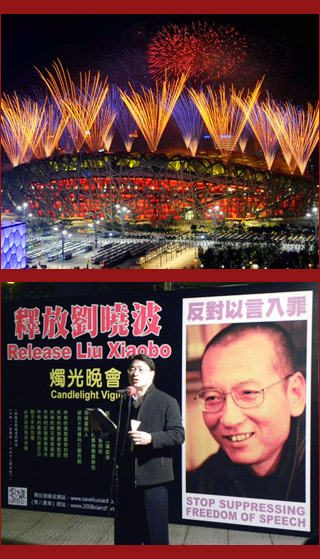

The biggest successes of this re-branding drive have depended on Beijing’s ability to ride the tide and take advantage of distinctively global aspects of the current era. Without far-flung supply chains and fast-flowing foreign investment – including that of ethnic Chinese in Taiwan and other locales – China could not have surged past Japan to become the world’s second largest economy. And without satellite television and the internet, the visually stunning opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games and strong showing by Chinese athletes could not have had the dramatic impact they did in 2008, helping dispel at last the lingering visions of China as a technologically backward “sick man” of Asia.

Yet when this re-branding drive stumbles, as it has periodically in the two years since the Olympics, this too is often due to the special nature of the current period of globalization.

The Nobel Peace Prize going to prisoner-of-conscience Liu Xiaobo, someone Beijing lobbied hard to keep from receiving the award, is the latest example of how difficult the Communist Party finds it in these robust global times to call the shots with international bodies. Before Liu got his prize, the 2000 Nobel for literature went to the Paris-based author and critic of the government, Gao Xingjian. This carried a special sting – due to what Julia Lovell, author of a book about Gao’s win, calls “China’s Nobel Complex.” China’s leaders have argued for decades that the PRC has become the kind of country that should be producing Nobel winners in many fields. They see it as cruelly ironic that, while some Chinese are indeed becoming Nobel laureates, they are honored not for breakthroughs in areas such as economics or medicine, but for writings that Beijing insists are vile, the creations of miscreants or criminals who the West wrongly lauds as heroes.

Back to the 2008 Olympics and its symbolism, all did not run smoothly, of course, from the Chinese government’s point of view. There were rough spots in even this most successful to date of all Chinese “soft power” spectacles. For example, the torch relay, the longest and most elaborate in Olympic history, was supposed to be a grand symbol of China’s reengagement with every part of the world.

In the end, though, only some stops outside of China went as planned. Protesters angered by Beijing’s policies toward Tibet and other issues held demonstrations, some rowdy, to mark the torch’s arrival in cities such as Paris.

On the whole, though, domestic and foreign media reports tended to line up fairly neatly once the Games began. The main storyline was that, by successfully mounting such a grand show, China demonstrated how dramatically it had changed and that it was again a central player in world affairs.

Such a message was supposed to be carried forward by two subsequent events dubbed “Olympics” of a sort: the prestigious 2009 Frankfurt Book Fair, called an “Olympics for Literature” by Chinese media, and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, often referred to in China as an “Economic Olympics” or “Olympics of Technology.”

If all had gone according to plan, the Frankfurt fair would have generated domestic and international headlines trumpeting the growing profile of Chinese literature and increased respect for China’s cultural traditions.

Things began to go wrong for China a month or so before its October opening, when a seminar linked to the event was scheduled to take place including writers who have drawn Beijing’s ire. Poet and dissident-in-exile Bei Ling was among those invited to take part, and so was Dai Qing, the China-based environmental activist whose writings are banned from publication in the PRC. Beijing expressed displeasure at this lineup and called on German organizers of the session to pull invitations to the writers the government found objectionable. At first, fair representatives did an about-face and sought to placate the Chinese government by revoking the invitations, but in the end, the authors came and spoke.

The result was a public-relations disaster, as the big story of the fair became Beijing’s ham-handed efforts to limit freedom of speech in an international venue and bully Germany – undermining in basic ways visions of the PRC 2.0 as a country that has become much less ideologically rigid and a more congenial participant in global affairs than was Mao’s China.

Flash forward one year, and we see a parallel situation – but with a higher profile in the international news. From Beijing’s point of view, October 2010 was supposed to be a month when the news coverage of the PRC dealt with upbeat topics such as China closing in on claiming record visitors for a World’s Fair–a record that currently stands at 64 million and is held by regional rival Japan for the Osaka 1970 Expo. Readers can find those stories about the Shanghai Expo, of course, but almost exclusively in the Chinese press. The biggest story internationally is Liu winning the Nobel Peace Prize, despite or perhaps partially because of Beijing pressuring the Norwegian committee in charge of the award to give it to someone – anyone – else.

Beijing has claimed – in venues such as the Global Times, an English language paper linked to the Communist Party – that Liu’s win reflects anti-PRC “prejudice” and “extraordinary terror of China’s rise and the Chinese model” in the West. However well or badly this rhetoric plays to domestic audiences, to most foreigners it comes across as strident and paranoid and does nothing to help brand China as a modern country.

The road from the Opening Ceremonies of August 8, 2008, to this year’s Nobel Peace Prize award has not been smooth for Beijing’s re-branding drive. One common thread in the story of this campaign, though, is that both high points and low points involve global events and new technologies.

After all, Liu is in prison not for a paper petition he helped draft and for which he collected signatures from people wielding pens. Rather he was given an 11 year sentence on charges of “subversion” for his role in Charter 08, a bold call for expanded civil liberties intended from the start to be distributed online, via the internet, a new media technology that censors in Beijing work overtime to control, especially at time likes this. Not long ago the same medium was dubbed “God’s gift to China” by an activist and writer once less known but now world famous – Liu Xiaobo.