China’s Global Governance Challenge

China’s Global Governance Challenge

NEW HAVEN: China is making waves again, not just in the South China Sea, but in the world of development finance as well. Just as the economy shifts support from external to internal demand, the nation’s worldview is going through an equally dramatic transformation.

The inward focus on domestic stability, one of the hallmarks of the “reforms and opening up” of Deng Xiaoping during the 1980s, is now being augmented by an outward-facing focus on China’s emerging role as a global leader, a key ingredient of the “China Dream” espoused by Party Secretary General Xi Jinping. These two sides of the same coin underscore the daunting challenges China faces in its search for a more sustainable development strategy.

There has been a rich discussion of China’s economic-rebalancing imperatives, shifting the growth engine from manufacturing and exports to services and private consumption. By contrast, the bulk of the debate over China’s new outward-facing geostrategic role has largely been framed in situational terms. That’s certainly true of recent territorial disputes in the East and South China seas, but it’s also the case in China’s “One Belt, One Road” plan for pan-regional integration – stretching from East Asia to the Middle East, North Africa and Europe. Missing in this discussion is a deeper examination of the strategy and principles of institution building and the role they will play in forming the foundations of China’s regional development aspirations.

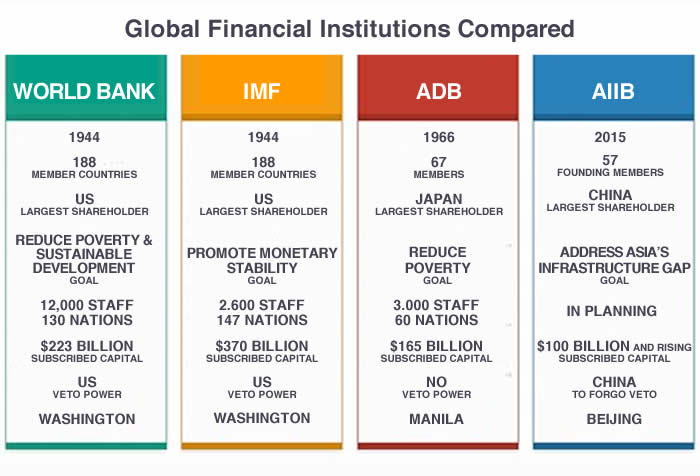

Topping that discussion list is global governance – in particular, the standards and processes that define the effectiveness of international institutions. China faces a steep learning curve as it attempts to integrate institution building into the global policy architecture. Until now, the nation has largely been a follower, not a leader, in shaping the conventions of global governance. As an active member of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the World Trade Organization, the United Nations and more, China has developed a keen appreciation of the norms of western governance. But now China is engaged in global institution building of its own – the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New (BRICS) Development Bank. And that casts China in a new and important role in the global governance debate.

This is not just theoretical conjecture. Later this month, the first general meeting of the 57 members of the AIIB will be convened in Beijing. A leading item on the agenda is governance – signing and unveiling the articles of agreement that were finalized at a late May negotiating session in Singapore. While China has taken the lead in driving the establishment of this institution, slated to commence operations by the end of 2015, it knows full well that it must be open and judicious in framing the broad parameters of its governance. The AIIB’s ultimate effectiveness will hinge on the broad membership’s acceptance of the new norms of its operating procedures. Success will be measured in terms of collective buy-in, not on the heft of China’s outsized initial capital contribution of around $25 billion.

Institutional governance is a complex topic that covers a wide range of organizational guidelines and operating conditions. Three key aspects of global governance will be crucial for a successful launch of the AIIB – transparency, representational voting rights and compliance. When the articles of agreement are made public in late June, they need to be evaluated from each of these perspectives.

First and foremost, transparency of the lending process is absolutely vital if AIIB is to fulfill its mission in helping to fund Asia’s massive infrastructure gap – estimated by the Asian Development Bank at some $8 trillion by 2020. Full disclosure of loan covenants and requirements for project approvals – including rates of return, environmental impacts and compliance with the global norms of labor and procurement standards – are essential. In the same sense, it would be helpful to have a clear sense of the AIIB’s overview of Asia’s infrastructure imperatives. That would provide a framework, or roadmap, for assessing how specific projects fit into the grand scheme as well as complement other regional efforts such as China’s Silk Road Fund, its related “One Belt, One Road” initiative, and lending programs of the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank.

Second, a credible representational voting mechanism is required for the effective operation of any international institution. While it makes sense to allocate votes in accordance with the capital contribution of the 57 founding members, the governing board of the AIIB should make an effort to avoid the pitfalls troubling other international institutions – namely, the veto power of large contributors that has long clogged decision-making at the IMF, the World Bank and the UN. It is reassuring that China apparently will not have such power in the AIIB.

Related to this are organizational leadership conventions. Just because the West has clung to now antiquated leadership conventions for the two Bretton Woods institutions – with a European head of the IMF and a US head of the World Bank – it would be imprudent of China to insist on a Chinese head of the AIIB in perpetuity. It’s only a matter of time before the IMF and World Bank adopt a more open leadership selection process. China and the rest of the AIIB membership should take the lead in framing a more enlightened approach to leadership selection. Similar considerations pertain to the structure of the AIIB’s 12-member board of directors – especially the balance between regional, non-regional and independent directors.

Third, robust and credible compliance procedures are essential for the effective governance of any successful international institution. Compliance not only legitimizes the standards embedded in funding and lending contracts, but also shapes the dispute resolution mechanisms that are needed to arbitrate the inevitable give and take over large loans and their repayment schedules. It is equally important to align compliance procedures of a new institution like the AIIB with the norms of international legal standards as well as to build an internal legal staff that has the professional expertise on par with existing legal systems in the West. The appointment to AIIB general counsel of US attorney Natalie Lichtenstein, well seasoned in the legalities of multilateral organizations, is especially encouraging in this respect.

While transparency, representational voting rights and compliance should be at the top of the governance debate in the establishment of the AIIB, a host of other related issues should be considered, too. Successful governance of any institution is, of course, heavily dependent on the skillset and integrity of its professional staff. For a new institution like the AIIB, that means the highest priority needs to be placed on recruiting, talent management, retention and market-based compensation schemes. In addition, it’s equally essential to establish impregnable firewalls between the operating function of the organization and political agendas of national members. Political independence is absolutely vital for successful governance of the AIIB.

In the end, governance is only as strong as the weakest link in the chain. The 57 founding members of the AIIB have a rare opportunity to establish new global governance standards and shape infrastructure investment as insiders in setting up a new international lending institution. For those on the outside looking in – namely, the United States, Japan, and Canada – that role is not an option. And that’s a real pity.

Stephen S. Roach, a faculty member at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, is the author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China (2014).