China’s Image Sullied by Tainted Milk

China’s Image Sullied by Tainted Milk

the lives of children at home and consumers abroad

BEIJING: The flag flew, the music surged, and state-run television was filled with triumphant images of the Beijing Olympics and the successful Shenzhou VII spacewalk, marking, on Oct. 1st, the Chinese Communist Party’s 49th anniversary in power. But if the party had hoped to spend the day basking in the adulation of the Chinese people and the admiration of the world, it hadn’t counted on the reverberations of a self-inflicted body blow to Brand China – the tainted milk scandal.

At last count, 53 brands of dairy products in China, plus foreign brands made with Chinese milk ingredients including Cadbury chocolate and Lipton milk tea powder, have been found to contain melamine, a binding agent used to make plastics and floor tiles. Chinese dairy producers found another use for the chemical – adding it to watered-down milk, because melamine’s high nitrogen content makes the milk’s protein levels appear higher than they are.

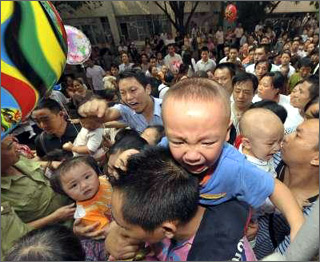

The tainted milk found its way into yogurt, ice cream, cakes, cookies, cereals – and, most unbelievably for many Chinese parents, who have been ordered by the state to have just one child, powdered baby formula.

“Some people are saying the presidents of those milk companies should be executed, and I think they’re right,” says grocery store owner Tian Yang Qing, as she glances through a government-supplied list of dozens of tainted products. “How could those businessmen do this to little babies? Think of how the children’s development is affected. Think of how their lives are affected. It’s terrible.”

Some 54,000 Chinese children have ended up in the hospital after drinking melamine-tainted milk formula, and at least three have died. Other children have been hospitalized with kidney stones in Hong Kong and Taiwan. So far, Chinese authorities have arrested at least 27 people in connection with the crisis.

The global response since the scandal broke in mid-September has been swift. More than a dozen countries have banned some or all dairy products from the affected brands. The European Union slapped a ban on any baby food originating in China that has even a trace of milk. Some analysts estimate it could take until 2010 for the $20 billion Chinese dairy industry to regain what it’s lost in credibility and sales – and that’s assuming China’s leaders get serious about enforcing a rigorous and transparent quality-inspection system, something they’d promised to do after the last year’s food safety scandals.

China’s leaders have been scrambling to send reassuring messages. “The problem shows that we should pay more attention to business ethics and social morality in the development process,” Premier Wen Jiabao told a World Economic Forum meeting in Tianjin. “These are some of the growing pains of China’s road to economic reforms. We will overcome them by facing the challenges truthfully.”

But Wen himself sounded less than truthful in another remark he made in the same speech. “China did not intend to cover the truth when the incident happened.”

The state-run media have reported a different story. It is a story about managers of a major Chinese brand, Sanlu, knowing as early as last December that its powdered baby formula had problems, but doing nothing. It’s a story of a father, 40-year-old Wang Yuanping of Zhejiang province, worrying as far back as February about why Sanlu’s powdered milk was making his daughter sick. He was persuaded to shut up with the free supply of four cases of the same.

It was not until early August that Sanlu informed local government authorities of the problem. By then, just days before the opening of the Beijing Olympics, local officials knew better than to spoil the celebration. Weeks went by. More children fell ill. Eventually, in mid-September, the New Zealand government intervened with Beijing on behalf of Fonterra, a New Zealand company, which owns a 43 percent share of Sanlu. The hushed-up story was finally blown wide open.

As an online editorial on Access Asia, a China and Asia consumer market analysis group concluded, “Fonterra knew something was wrong. They decided to try and deal with the problem internally, worried about the negative effect on Sanlu, on China during the Olympics and of course on themselves.”

But this isn’t a story about just one bad actor. It’s about dozens of Chinese dairy producers and collectors, gaming the quality-inspection system over time, adding not just melamine but also, in the past, other chemicals, so they could water down their milk, pass cursory quality inspection tests and make more money. It’s also about a state regulatory system that failed.

“In any (regulatory) system, you can’t rely on testing alone,” says Jorgen Schlundt, director of the World Health Organization’s food-safety department. “That’s the old-fashioned way. You have to have a system where you look at what are the risks and how do we prevent them, as close to the source as possible. You need to have a system where you have a culture of openness and quick reporting.”

That’s exactly what China does not have. Instead, it has a system where many businesses try to get away with what they can, and many local officials try to cover up problems that happen on their watch, either because they’re profiting from the businesses in question, or because they fear that problems could cut into their chances for a raise or a promotion. That mentality has delayed reporting in recent years on SARS, bird flu, toxic chemical spills and food contamination. In each case, local officials preferred to risk other people’s lives than their own careers. The central government’s warnings that it would fire those who don’t report promptly have failed to transform the old mentality.

Meanwhile, consumer protection mechanisms in China remain weak, and the government appears to want to keep them so. About 20 of the lawyers who have been trying to help families affected by the tainted milk scandal say they have received calls from local governmental legal authorities, warning that they could lose their licenses if they continue to help affected families.

What the government appears to fear, in this case as with previous class-action attempts on property and pollution, is a snowballing effect that could lead to a national political movement. It seems to prefer to keep victims isolated from one another, while stressing social harmony and promising to pay medical bills and fix the problems.

Premier Wen has now pledged to overhaul the quality-inspection system for food and dairy. One problem, says the WHO’s Schlundt, is that up to 16 different authorities now split that responsibility: “It is always a problem when you have many separate authorities that may not have the same culture of reporting.” He says it’s a good first couple of steps that China has put the Food & Drug Administration under the Ministry of Health, and suspended a system that allowed some favored companies, including Sanlu, to do their own quality inspection. But a thorough reorganization will take years.

Meanwhile, there’s urgent damage control to be done. Without swift and effective action to better protect its own consumers and citizens, China’s leaders may find that the wave of goodwill they’ve been riding of late may dry up, and bring them down to earth with a thud.

Mary Kay Magistad covers Northeast Asia for The World.