Chinese Chess in Space

Chinese Chess in Space

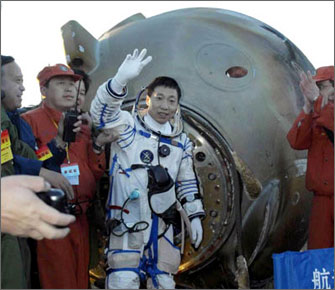

NEWPORT, USA: Over three millennia ago, the Chinese invented Wei Qi (pronounced way chee), a type of chess game with 361 pieces that allows for immense strategic complexity. Generations of Chinese leaders have studied the game in order to hone their decision-making skills. Today China views long-term geostrategic politics as having a similar number of possible permutations as a Wei Qi board, and Beijing is posturing accordingly. When Yang Liwei completed China's first manned space flight last October, China made a significant geostrategic Wei Qi move. The next move goes to the United States, and President Bush appears ready to make it. While a space race is not a foregone conclusion, it is a possibility.

The United States is considering a new space initiative. Whether the Moon, Mars or something in-between or beyond, that's the what. Equally important is the how, as the devil is always in the details. In this geostrategic game of Chinese chess, the United States has three basic options. It can do nothing, which equates to sending congratulations and then continuing a status quo policy excluding China from cooperative space efforts. Alternatively, the US can explicitly commence with a new manned space race reminiscent of the US-Soviet competition during the Cold War. Or, the US can initiate an incremental program of cooperation between China, the US, and other international space partners. In deciding between these options, it is important to remember that while Wei Qi involves two players, here other players are simultaneously involved. This complication both influences maneuvering alternatives and increases the significance of the Washington's next move on the larger geostrategic gameboard. All things considered, cooperation is the best long-term choice for the United States.

Doing nothing is likely not a viable long-term option. Though the US public was initially apathetic about Yang Liwei's flight, that could change. As the Chinese continue their ambitious manned space plans while the US Shuttle is grounded, the US will likely be perceived as having been overtaken by the Chinese in manned space activity. Chinese technology will not really have outpaced US technology, but Beijing's sustained political commitment will have. Additionally, while the US ignores China, the Chinese are seeking out and increasingly finding other countries favorably disposed toward working with them. The Chinese are already participating in the European Galileo navigation satellite program that could challenge the Global Positioning System developed and still completely controlled by the US. In sum, public perception-cum-prestige considerations and “control” issues make maintaining the status quo unacceptable.

Alternatively, the United States can declare a space race, unilaterally announcing a long-awaited manned program to return to the Moon and/or a manned Mars mission. However, the International Space Station (ISS) partners, especially Russia and Europe, are unlikely to support a program developed without their input or one that excludes the Chinese. Further, the continuing financial and technical problems with the still-incomplete ISS make it unlikely that they would be anxious to commit, even if invited, to an expanded manned program. So if the US were to start another space race, it would likely be going it alone.

Domestically, a competitive approach would accrue benefits to the US like those enjoyed during the Apollo program, including prestige, technology development, and jobs. Strategically, at the risk of otherwise losing face and allowing the technology gap to grow, China would be pushed toward increased spending on its manned program and at a faster pace than they would otherwise choose. That would divert funds from Chinese military programs and potentially cause China substantial economic hardship, similar to what happened when the Soviet Union felt compelled to spend money countering Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) technology.

But there are three critical uncertainties that would make initiating a space race an unwise move - whether the US can afford an independent program and maintain the requisite political will to fund it through completion; whether it is really the best long-term strategy for long-term US-China relations; and whether the US can afford to reinforce further the view that it prefers unilateralism to multilateralism - in any realm of international relations.

It can be argued the United States does not really need to stay the course and bring a new space race to a conclusion, as the unfinished SDI program still significantly impacted the Soviet Union. But to start with anything less than a full commitment sets a new program up for failure. US history is replete with space visions and programs set forth from podiums and later forgotten. Although wrapping a manned space program within a larger strategic vision is important and useful, political competition has far more short-term motivational impetus then long-term staying power.

Additionally, Americans' desire and ability to carry the economic burden alone must be considered. Public support for paying the entire bill for a new manned space program is doubtful. Manned space exploration has been consistently viewed by the public as a good thing to do, but low on its list of funding priorities.

Equally important is whether a competitive race with China is in the best interests of the United States. While spending the Soviets into bankruptcy unquestionably played a role in the eventual fall of communism in the Soviet Union, dealing with Russia as a near failed state in the subsequent years is not a model to deliberately set up in China.

The third alternative focuses on cooperation. The US has a long and successful tradition of international cooperation in space. Especially in the areas of space science and environmental monitoring, the US has historically viewed space as an opportunity to build bridges with countries while simultaneously co-opting them into working on areas of our choice, rather than areas not to our liking. Cooperation is clearly the better option with China, too. The US could start slowly, rewarding Beijing for reciprocity and transparency by granting China an increasingly larger role in a joint program of manned exploration and development.

Specifically, a US proposal to multilaterally review and expand the future of manned space exploration - from the ISS to another lunar voyage or even a Mars mission - on an incremental, inclusive basis would allow Washington to revitalize American space leadership. Crucially, it would also give the US a means to influence the future direction of the Chinese space program. This option would counter the prevailing view of the US as a unilateralist hegemon and allow for a focus on infrastructure development that does not require unrealistic budget burdens. While there is the risk of international politics intruding into the process over time, that is counterbalanced by the vested interest such a program would give participants in system stability.

To be sure, there would be resistance to working with China. Washington is replete with individuals adamantly objecting to cooperation with China on grounds from human rights to its status as the largest remaining communist country. Isolating China, however, is increasingly a stance counterproductive to US interests, as a world without China is simply not possible. US and Chinese interests frequently overlap, on North Korea and the Global War on Terror, for example, not to mention economics.

The United States has a window of opportunity to step in and use space cooperation to its advantage. Because space is considered so critical to the futures of both the US and China, any activity by one has been considered zero-sum by the other, triggering an action-reaction cycle and threatening escalation into an arms race of technology and countermeasure development. That direction can be changed. A inclusive vision will give the US an opportunity to assume the mantle of leadership on a mission that could inspire the world and shift Chinese activities into areas more compatible with US interests. On the geostrategic Wei Qi board, cooperation is the best "next move" for the US.

Joan Johnson-Freese is Chair of the National Security Decision Making Department at the United States Naval War College. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the official position of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the US government.