Citizenship of Convenience

Citizenship of Convenience

TAIPEI: “America is the greatest country in the world with one of the worst health insurance schemes in the world.” This sentiment is echoed by many Taiwanese nationals and articulated by Andrew Lin, a Taiwanese-American who currently resides in Taiwan. Conversations with Taiwanese like Lin show a growing frustration with the economic status of Taiwan, as they look to countries as diverse as the United States and Mainland China for greater opportunity. Many, as Lin’s parents did, make the journey to the United States or Canada to secure opportunity in the form of a foreign passport.

A few citizens are taking advantage of eased travel regulations to procure health care – and this could lead to new citizenship and economic problems for countries like the United States and Taiwan.

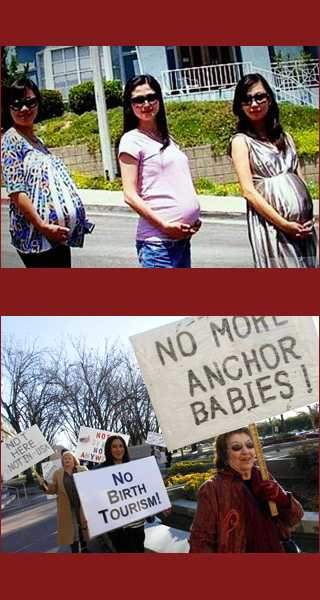

Families by the thousands secure travel visas and head to the United States, Canada and other nations with the hope of giving birth abroad. This phenomenon, common among Turkish, Chinese and Taiwanese nationals, has grown in recent years and become a business. Private companies transport, house and provide the necessary arrangements for so-called birth tourists to enter the country and stay until they give birth. Taiwan is of particular significance because of its affordable healthcare for citizens and positive relationship with the United States and Canada.

The United States on November 1, 2012, adopted a visa-waiver program with Taiwan, which could create significant financial problems for the Taiwanese and complications for the United States and its ongoing immigration debate. Increasing birth tourism and a larger number of individuals returning to Taiwan to take advantage of affordable medical insurance and low medical costs will raise insurance premiums for all Taiwanese, increase the number of citizens who return to Taiwan to claim cheaper health insurance and put a heavier burden on US taxpayers for public schools.

The number of individuals seeking reinstatement in Taiwan will continue to increase. According to the Taiwan Bureau of Health, the number of citizens who return to Taiwan for medical procedures is estimated at 50,000 returnees per year and expected to increase as health care costs globally go up. Meanwhile, birth tourism may be on the rise, with the US-based Center for Immigration Studies estimating that of the more than 300,000 children born to undocumented residents in the United States every year, 40,000 are to tourists. The National Center for Health Statistics tallied 7,670 births to mothers who used a foreign address. However, this number is likely a low estimate due to birth tourist mothers often using a hotel or current US address for the child’s birth certificate. This rise of birth tourism could increase the number of dual-citizen Taiwanese and the number of individuals returning to Taiwan for health-care reinstatement.

Conversation after conversation with Taiwanese in Yilan County reveals deep frustration with the fairness of the National Health Insurance program. A payroll tax for the Taiwanese workforce pays for these low-cost health-care premiums. Under current regulations, as of January 2013, returning Taiwanese need only pay six months of insurance premiums to be reinstated. The National Health Insurance has run a deficit for the past several years; premiums are in the hands of the legislature predicted to continue to rise.

Lifting travel-visa requirements for Taiwanese will undoubtedly ease the challenges to birth tourism and add to the US immigration problem. While most Americans are familiar with "anchor babies" – immigration by parents using the US citizenship of their babies as a means towards their own citizenship – birth tourists generally do not seek US citizenship for themselves. Instead, their children, born in the US and raised in Taiwan, often return as high school or college students to take advantage of less expensive, even free, and better education not to mention other services available to American citizens. Neither the children or their parents have paid into the system, instead relocating back and forth to pick up quick benefits.

So, both sides of the Pacific are saddled with significant and risings costs. According to reports by the Taiwan Ministry of Health, in 2011, reinstatement costs were US$ 567 million while medical costs incurred were over US $700 million. The gap is increasing, in 2010, medical costs minus reinstatement costs were less than US $100 million. While the recent policy adoption of a six-month premium reinstatement aims at closing this gap somewhat, it’s not enough. Meanwhile, if the current trend continues, the United States will certainly face a larger number of Taiwanese-American citizens hoping to return to the country as students in US public high schools.

There are multiple answers for these two countries that are much simpler than amending the US Constitution or further altering Taiwan’s premium payable schedule. The first response is creating a more positive economic climate in Taiwan. Stephen Chen, a Taiwanese-American who lives in the United States, points to economic disparities as a key reason behind such relocations: “It's easier to find a job [in the United States] than in Taiwan, at least that's the perception [in Taiwan].” While economic growth in Taiwan has remained at a constant, steady increase over the last three years, perceptions of security are not so high, as revealed by the approval rating of President Ma Ying-Jeou and his party’s economic policies, which have fallen below 20 percent, according to The Economist. Creating greater economic security rather than sending jobs to Mainland China, the United States or Canada – at least the perception of security – could reduce birth tourism somewhat and retain workers in Taiwan.

Secondly, Taiwan and the United States could adjust immigration laws to account for birth and medical tourism. While arriving in the United States as a pregnant “tourist” is not illegal, misrepresentation on visa forms and during interviews with Immigration and Customs agents is a federal offense. Gary Chodorow, a Beijing immigration lawyer, points out that birth tourism companies coach immigrants on what to say to customs officials and how to fill out visa forms, albeit deceptively. The United States could deter birth tourism with harsher penalties or stricter enforcement. Hong Kong recently employed similar strategies, reducing the number of Mainland China mothers immigrating to Hong Kong to give birth to below 35,000 per year, according to Beijing-based Caixin.

In Taiwan, a drastic but reasonable measure could be to end dual citizenship for health care benefits. This would mean that at 18 or 21 years of age, adults would have to choose which citizenship to recognize. If the individual chose the United States, the individual could not return to Taiwan for National Healthcare and instead would use US or traveler’s health insurance.

Thirdly, other Taiwanese pursue foreign passports for their children as necessity, out of fear of regional instability with a hostile North Korea and China. Countless Taiwanese parents remember the 1996 Taiwan Strait crisis and earlier crises, and regard an escape plan for their children as necessity. Chen voices the concern of many Taiwanese: “the most effective way for us to decrease the rate of birth tourism is to promote peace and stability in regions where birth tourists originate and to strengthen mutually each other’s economic development.”

Few can fault individuals for seeking economic opportunities for their children in tough financial times. The United States and Taiwan must work together to regulate transient citizens who seek benefits and rights without taking on the responsibilities of citizenship – or the consequences could be costly, ruining travel opportunities for all.

Tyler Grant is a graduate of Washington and Lee University. He is currently a 2012-2013 Fulbright Fellow to the Republic of China – Taiwan. The author will field readers’ questions for a week after the publication date.