A Clash of Civilizations in Europe?

A Clash of Civilizations in Europe?

PARIS: A year after the wave of violent demonstrations throughout the Muslim world, protesting the publication of caricatures of Mohammad by a Danish newspaper, frictions between Europe and the Muslim world multiply, threatening to make the “clash of civilizations” a self-fulfilling prophecy:

Pope Benedict XVI outrages the Muslim world by quoting remarks critical of Prophet Mohammad by a 14th-century Byzantine emperor.

Berlin’s Deutsche Oper considers canceling the staging of an opera by Mozart, for fear a scene exhibiting the severed heads of several prophets, including Mohammad, might incite Muslim violence.

A French philosophy teacher flees and lives under police protection, targeted for murder by Islamists, after writing an op-ed piece that attacked Mohammad’s blessing of violence in the service of religion.

Former British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw unleashes a furor by calling on Muslim women to remove their veils, suggesting that not being able to see a person’s face made him feel “uncomfortable.” Amid Muslim protests, incidents of harassment of veiled Muslim women have been reported.

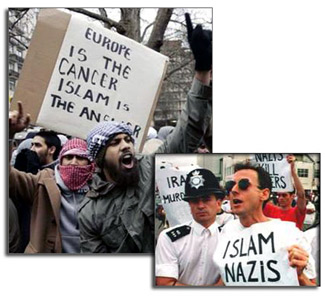

These controversies move beyond the usual xenophobic and anti-immigration concerns of the far right about the perceived intolerance, aggressiveness and even incompatibility of Islam with European core values. They also feed dangerous strains of “Islamophobia” throughout Europe.

These “clashes” are to some extent a toxic byproduct of a globalized media system. Instant information and misinformation, through satellite TV and the internet, tend to obscure complex issues, feed on widespread ignorance on both sides and pour oil on long-simmering fires of historical resentment, economic frustration and political conflict. The large and fast dissemination of extremist minority views on isolated events whip up collective passions, making a dialogue based on tolerance and rational criticism more difficult. To that extent, it might be argued that globalization plays in the hands of Islamists who preach “jihad,” or holy war, against the West, and those who dream of Europe walling itself against Islam.

Conflicts between a fundamentalist version of Islam and European societies based on secularism, liberal democracy, individual rights and non-discrimination of the sexes reawaken in European minds ancient fears, steeped in centuries of wars and invasions – all the more so since the phenomenon takes place under the persistent threat of Islamic terrorism, which has struck Madrid and London since 2001 and targets other large European cities. Conflict is aggravated by the pressures born out of immigration from Muslim countries across the Mediterranean, which has made Islam, with more than 20 million believers, one of the European Union's major religions,. The conflict is also highlighted by the debate around the candidacy to the EU of Turkey, whose 60 million Muslim inhabitants have elected an Islamist-influenced government.

Robert Redeker, a 52 year-old French philosophy teacher and author, known for his abrasive criticism of all religions, launched a virulent attack on Islam in the September 19th issue of the conservative daily “Le Figaro” – savaging the blessing of violence in “The Koran” and harshly characterizing Mohammad as a “teacher of hatred – looter, Jew-killer and polygamist.” The next day, the popular Egyptian preacher Youssef al-Qaradawi denounced Redeker on Al-Jazeera TV, and Redeker received death threats after an Islamist group posted his address, cell-phone number and photos online and called on Muslim “lions” to kill him, as Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh was killed in 2004 in Amsterdam by a 27-year old immigrant from Morocco. Van Gogh outraged militants by making a film denouncing the oppression of women in Islamic societies.

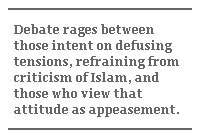

Redeker's predicament, reminiscent of British author Salman Rushdie’s after Ayatollah Khomeini's 1989 fatwa calling for his murder, has roused support from French unions, civil liberties defense groups and politicians of all stripes. Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin denounced the threats as “unacceptable” and defended “freedom of expression.” The incident has fueled a debate between those intent on defusing tensions by refraining from criticism of Islam and those who view that attitude as appeasement.

Redeker's essay, admittedly provocative, was written to protest Pope Benedict's apology for a speech given September 12th in Ratisbonne, Germany. The Pope had quoted Emperor Manuel II Paleologus who, circa 1400, assailed use of the sword to spread Mohammad's teachings. The quote prompted furious protests from Islamic preachers, threats of diplomatic retaliation by Muslim governments and violent street demonstrations that led to the murder of a nun. Benedict XVI expressed his regret for a “misunderstanding.” To Redeker and many other Europeans, the Pope's apology smacked of appeasement.

The sense of a creeping surrender of central values such as freedom of expression and the right to criticize, and even lampoon any creed and faith, was compounded by the decision of Berlin's Deutsche Oper director to cancel showings of Mozart's “Idomeneo” for fear of violence by Islamist extremists. German Chancellor Angela Merkel reacted: “Self-censorship out of fear cannot be tolerated.” The September 30th headline of the daily “Libération” asked: “Is it still possible to criticize Islam?” The opera, originally scheduled for November, may yet be performed later under police protection.

The absence of clear denunciations by moderate Islamic theologians, preachers and representatives to calls of violence and censorship is perceived as a sign of Islamists’ growing clout. It also feeds suspicions that silencing criticism of religion is, like female oppression, part and parcel of Islam. The threats against France, recently reiterated by Al Qaeda deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri, for the 2004 law prohibiting the Islamic veil in schools and public-service jobs have reinforced the feeling that Islam is trying to force its prejudices on secular European societies.

On the one hand, then, Muslims react more violently and internationally to criticisms they deem “blasphemous” and “Islamophobic.” On the other, books and essays denouncing Islam as “the new totalitarianism,” in the line of fascism and communism, have been popular since the 2002 anti-Muslim bestseller by Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, “The Rage and The Pride.” European fear of a “green peril” is a mirror image of Muslim phantasms of a Western conspiracy against Islam,” an inexorable spiral of false perceptions fueled by the media cauldron of instant TV images and internet pronouncements by radicals.

All this obscures the fact that Muslim furor, as shown during the caricature controversy, is often staged for media consumption by small groups of extremists while the vast majority of Muslims remain indifferent. Over 70 percent of Muslims living in Europe, according to a 2005 European-wide study, describe themselves as hostile to Islamists. Most practice a peaceful and tolerant brand of Islam, and many wish for the emergence of a European form of Islam, through reforms that adapt the faith to the modern world.

But a daily diet of violent news, images and threats – many bloodthirsty acts by Muslims against other Muslims – hides to European eyes the extreme diversity of Islam and its deep divisions along sectarian, ethnic or theological lines. The silence of tolerant Muslims ends up making militant Islamism the only message of Mohammad heard by Europeans, the very aim of proponents of “jihad” and xenophobes. The dire prediction of André Malraux, made half a century ago, might one day become true. “The political unification of Europe would require a common enemy,” said the author and Gaullist minister of culture in 1956. “But the only possible common enemy would be Islam.”

Patrick Sabatier is a French author and columnist.