Clearing Clouds Over the Karakoram Pass

Clearing Clouds Over the Karakoram Pass

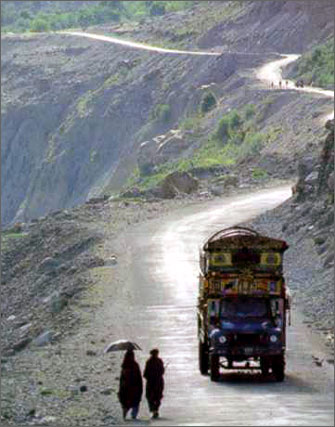

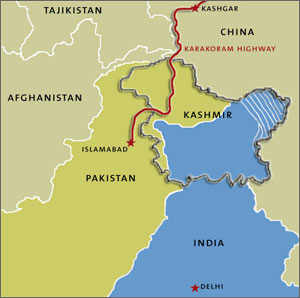

ISLAMABAD: The Karakoram Highway, running from China's Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region to Pakistan, is more than a symbol of the two countries' "all-weather" friendship. It is a strategic link that brings China directly to South Asia. This 500 mile-long highway has, however, been buffeted by Islamic radicalism. Growing Chinese pressure has forced the Pakistani government to take on the new challenge brought by the flow of militant ideology and arms along this crucial artery of Sino-Pakistani relations.

Since its opening in 1982, the Highway has facilitated trade and people-to-people contact between the two countries. It has increased China and Pakistan's control over their frontiers and capability to deal with security threats from India and elsewhere. Upon its completion, China's deputy Premier Li Xiannian publicly stated that the Highway "allows us [China] to give military aid to Pakistan." What Li had not foreseen is that China's opponents could also go in the other direction - bearing arms and threatening China's security.

That new threat has emerged in part from Pakistan's religious links with the Uighurs, who have long agitated against Chinese rule. The Uighurs are a Muslim people of Turkic origin. They continue to feel culturally and politically alienated from the Han Chinese, the majority ethnic group in China. In the 1990s, some Uighur groups resorted to terrorism in pushing for independence, though most Uighurs have peacefully made their voice heard. Their political ambitions have shifted away from demanding independence to calling for greater autonomy and reforms, including increased economic opportunities and religious freedom. Beijing, however, has viewed any sign of protest as a threat to its control over a region whose abundant natural resources and strategic location vis-a-vis Central and South Asia make it indispensable to China.

In the early eighties, all was still quiet on the western front. The Highway was opened during a period in which Beijing began to relax its political and economic grip on China. Uighurs greatly benefited from the freedoms afforded to them; some began traveling to Pakistan to conduct trade, or in transit to perform the Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia. Others enrolled in Pakistani schools. Many Uighurs settled and raised families in Pakistan. Free exchange and movement along the Highway, as well as stable Uighur-Beijing relations, proved pivotal to friendly Uighur-Pakistan relations.

For many Uighurs, though, Beijing's concessions remained too narrow. Increased Han Chinese settlement in Xinjiang and job discrimination were major sources of friction, as were family planning policies. The income gap between Xinjiang and other provinces also continued to increase throughout the 1980s.

As Uighur discontent fused with increasingly authoritative policies, the region descended into a vicious cycle of violence that lasted through the 1990s. Incidents ranged from Chinese authorities firing on innocent Uighur protesters to Uighur separatist groups setting off bombs in Xinjiang's capital city, Urumqi, during Deng Xiaoping's state funeral in 1997.

Along with suppressing dissent within Xinjiang, the Chinese government sought to insulate Uighurs from external forces that could destabilize the region. At the top of Beijing's agenda was stemming the flow of Islamic ideology and militant Uighurs along the Karakoram Highway.

Many Uighurs who crossed into Pakistan in the eighties enrolled in madrassas that promoted radical views. They studied under the patronage of groups such as the Jamiat-i-Ulema Islami and were recruited to fight in the Soviet-Afghan war. At the end of the war, the Highway funneled them back into Xinjiang where they joined violent Uighur nationalist movements.

With the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan, China's fears were further compounded. The Taliban and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), a jihadi group with ties to Al-Qaeda, began to recruit Uighurs from the vast network of Pakistani Deobandi madrassas. Chinese authorities have claimed that more than one thousand Uighurs fought in Afghanistan alongside the Taliban and Al-Qaeda during Operation Enduring Freedom.

The influence of radical Islam on the Uighur separatist movement is clear, but it remains limited. Uighurs practicing a moderate Sufi form of Islam, and the Chinese government's success in restricting religious activities may explain this. Nevertheless, China has been quick to capitalize on the global war against terror to launch a 'Strike Hard' campaign in Xinjiang. This campaign has resulted in mass arrests, summary sentencing, and rampant executions.

China's efforts to consolidate its hold on Xinjiang have forced Beijing and Islamabad to maneuver around potential roadblocks and avoid damaging their relationship. In 1992, after a failed uprising near Kashgar resulted in 22 deaths, China closed its road links with Pakistan for several months. In 1999, the Chinese authorities lodged a protest with the Pakistan Interior Ministry upon the arrest of sixteen Uighurs who claimed to have received guerrilla warfare training in Pakistan-based camps. Chinese fears of Islamic fundamentalism within its borders have also disrupted land-based trade. The Sino-Pakistan land-based trade agreement that expired a few years ago has yet to be renewed.

Whether the Pakistani government was aware of Uighur militants' activities is difficult to say. While Pakistan has generally adopted a tolerant attitude toward the Uighur presence on its soil, it has never espoused the Uighur separatist cause. Since the late nineties, and with the advent of the US-led war on terror, Pakistan has taken increasingly stern measures to assuage China's fears and purge itself of Islamic extremism.

Islamabad has closed Uighur settlements and markets in Pakistan, forcing Uighurs out of local madrassas, and even killed wanted Uighur militants. Last December, Pakistani authorities stated that Hasan Mahsum, leader of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, was shot dead during a military operation to flush out Al-Qaeda members in South Waziristan. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement was designated a terrorist organization by Beijing in its first ever publicly released list of terrorist organizations in December 2003. These actions, along with the recently concluded Sino-Pakistan extradition treaty, make Pakistan's zero tolerance policy for Uighur militancy abundantly clear.

Islamabad's efforts to win back Beijing's confidence are clearly working. In the November 2003 China-Pakistan Joint Declaration, signed during President Musharraf's visit to China, both sides promise to conclude a new border trade agreement and “strengthen transport cooperation and promote interflow of personnel and commodities through the Karakoram Highway.” China is also heavily investing in the Gawadar port project in the Pakistani province of Baluchistan that can be used to transport goods to and from western China.

Pakistan's siding with China's “war on terror,” however, does not bode well for ordinary Uighurs in Pakistan who may be caught in future dragnets. Meanwhile, in Xinjiang, the Chinese government has used a carrot and stick strategy. It has invested heavily in the region allowing for job creation while clamping down on all forms of dissent. Today, an uneasy sense of peace has descended upon the region. There is a danger, though, that China's draconian policies to combat “terrorists” may polarize moderate Uighurs and create the problem they are aimed at solving.

As for Pakistan, it faces the challenge of dismantling the extremist infrastructure within by reforming madrassas and closing down training camps. Should it fail to do so, Islamabad could find itself playing an unwitting host to militant Uighurs once again, causing a severe rupture in the all-weather friendship. But for now, Sino-Pakistan relations are back on track, and the clouds continue to clear over the Karakoram Pass.

Ziad Haider (ziad.haider@aya.yale.edu) is a Research Assistant in the South Asia program of the Henry L. Stimson Center, a Washington DC-based think tank. He traveled through China’s Xinjiang province in 2002 while conducting research on the region.