Coalition in Turkey Could Alter the Country’s Foreign Policy Direction

Coalition in Turkey Could Alter the Country’s Foreign Policy Direction

NEW HAVEN: In an election on June 7 that will reshape Turkey’s political system, the governing Justice and Development (AK) Party lost its parliamentary majority. Though the country’s four main political parties are still jockeying over how to form a functioning coalition, it’s clear that the AK Party will no longer enjoy the monopoly on political power it has enjoyed in recent years and that could affect how Turkey deals with the world.

Though some of Turkey’s neighbors – many of whom have grown tired of President Erdoğan –will celebrate the end of his party’s majority, the new coalition politics inject great uncertainty into foreign policy. Nearly all of Turkey’s neighbors, from Syria to Greece, Iran to Israel, will find that their relations with Turkey depend on the complicated coalition bargaining that determines the shape of the new government and the approach it might take on foreign relations.

Given the deep contradictions among the opposition parties, the AK Party faces two basic coalition choices. It can form an alliance with the far-right nationalist National Action Party (MHP), or it can cut a deal with one of the two center-left parties, either the secularist Republican People’s Party (CHP) or the new Kurdish party, the People’s Democratic Party (HDP).

A right-wing coalition between the AK Party and the MHP would inject new tensions into Turkey’s relationship with nearly all of its neighbors. The MHP sees itself as the defender of Turkey’s interests, but many countries bordering Turkey see the party as a bully. The nationalist voters whom the MHP represents tend to have negative views of the many countries with whom Turkey has longstanding conflicts, including Greece, Armenia and Cyprus. A coalition agreement that brought the nationalists into government would likely worsen relations with each of these countries – and would likely rule out a deal to open the Turkish-Armenian border – an agreement almost implemented in 2009 which would boost trade and ameliorate conflict between the two nations. Such a coalition could also throw a wrench into talks currently underway to reunify the Greek and Turkish halves of Cyprus.

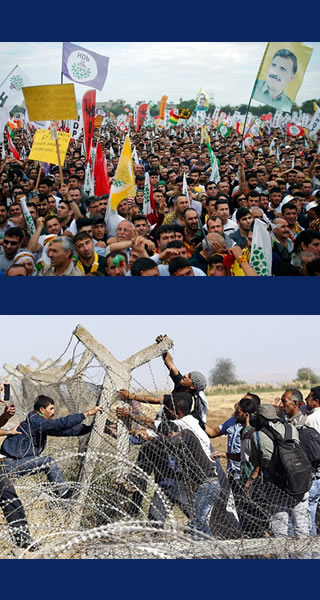

The greatest effect of a coalition with the nationalists, however, would be on the Kurdish question. Under AK Party rule, Turkey has taken great strides toward resolving its longstanding conflict with its ethnic Kurdish minority, which represent about 20 percent of the population. The AK Party rolled back restrictions on the Kurdish language, started talks with Kurdish leaders and competed for Kurdish votes in parliamentary elections. Though talks with Kurdish groups have not led to a final deal with the main militant grouping PKK, which had fought Ankara for a long time, the AK Party has gone further in normalizing relations with the Kurds than any other government in Turkey’s history. Indeed, the strong performance of Kurdish groups in the election – for the first time, a Kurdish party made it to parliament – was only possible because of the AK Party’s reforms.

A coalition with the nationalists, however, would torpedo any chance of resolving the Kurdish question. Such a coalition might well ignite a new wave of violence between Turkey’s government and the PKK, a conflict that would exacerbate tensions not only in Turkey itself, but also in Syria, Iraq and Iran—all countries with sizeable Kurdish minorities.

By contrast, if the AK Party establishes a coalition with either of the left-wing parties, and especially with the mostly Kurdish HDP, a deal with the Kurds could be at the center of the coalition agreement. A durable Turkish-Kurdish peace would have significant ramifications for the region. Much of Turkey’s foreign policy with regard to Iraq, Iran and Syria focuses on marginalizing the threat of Kurdish independence. If PKK militias were all disarmed as part of a peace deal, Turks would no longer fear Kurdish independence movements. In the long run, Ankara might find that, rather than opposing Kurdish groups in Syria, for example, it could work with them to expand Turkey’s influence. Relations with the Turkish region of Northern Iraq could also be expanded. Settling the Kurdish issue in Turkey might make Ankara more willing to work with Syrian Kurds against the Islamic State, also known as ISIS.

In addition to opening up new avenues for Turkish-Kurdish cooperation, an AK Party alliance with the left may well lead to a reduction of the role that Islamist ideas play in Turkey’s foreign policy. Over the previous decade, Ankara tried to play a large role in regional politics by building an alliance with the Muslim Brotherhood. For example, Ankara supported Brotherhood-linked parties in Egypt, Syria, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen. That excited some of the AK Party’s political base, which promoted the righteousness of the Brotherhood’s Islamist politics and its struggle against autocratic regimes. Yet many of Turkey’s neighbors saw Ankara’s pro-Brotherhood line as unfriendly meddling in local politics.

If the AK Party forms a coalition with the left, Turkey’s links with Islamist movements may be scaled back. The CHP is skeptical of mixing religion and politics, and has no great love for the Muslim Brotherhood. It has criticized the AK Party for placing ideological concerns ahead of practical ones, noting that the AK Party’s vocal support for the Muslim Brotherhood cost Turkish businesses lucrative contracts in Egypt.

Similarly, the Kurdish politicians have criticized the AK Party for supporting extremist Islamist groups in Syria and even alleged that Turkey’s government supported the rise of Islamic State terrorists. At the very least, Ankara turned a blind eye to the rıse of extremist groups in Syria. For example, Ankara was also slow to cut off the ISIS supply chains that reached into Turkey, though that is now changing. And Turkey was unwilling to defend Syrian Kurdish groups against ISIS attacks, a position that led the US to aid Syrian Kurds in the city of Kobane by targeting airstrikes against ISIS forces. If the AK Party were to seek a coalition with the Kurdish HDP, a more sympathetic relationship with Syria’s Kurds would be a likely precondition

Another result of an AK Party coalition with either of the parties on the left would be to reinvigorate Turkey’s long-delayed negotiations to join the European Union. During the early years of AK Party rule, Turkey made great strides in implementing reforms that were necessary for EU accession. Recently, though, relations between Ankara and Brussels have cooled sharply, in large part because of concerns over Erdoğan’s perceived authoritarianism after the government’s violent crackdown on protests in 2013 over construction plans on Istanbul’s Gezi Park.

Both the parties on the left, however, have made restarting the EU talks a centerpiece of their vision. Many within the AK Party, especially those around former President Abdullah Gül, are also thought to be unhappy with the lack of progress on EU talks, particularly since this sends a negative signal to investors. Rebooting EU negotiations could play an important role in a coalition agreement between the AK Party and either the CHP or HDP.

In other spheres, such as the country’s cold relations with Israel or its support for containing Iranian proxies in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere, the election and the coalition talks will be less significant, as there is less sharp disagreement among the parties. In nearly all of the countries that border Turkey, however, the main legacy of this election might be as a lesson about democratization. An Islamist party took power, defanged the secular military, governed for a decade and then lost power in fair elections. The vote proved that a rotation of power is possible, and that Islamist politics do not necessarily conflict with democratic governance. As they calculate how the coalition negotiations will shape their foreign relations, Turkey’s neighbors might also consider the lessons they can draw from the consolidation of Turkish democracy.

Chris Miller is a PhD candidate at Yale University and a research associate at the Hoover Institution. He is currently finishing a book manuscript on Russian-Chinese relations.