Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage

New Haven: Seen from abroad, American corporations are lining up behind American corporations to enter Iraq. European media has noted with concern that the first contract in Iraq to put out oilfield fires was awarded without any bidding to Kellogg Brown & Root, a subsidiary of US-based Halliburton, a company with long ties to the US military. The governments and business communities of France, Germany, and Russia - and even Great Britain - are concerned that their businesses will be left in the cold. We can't tell how this tension will play out, but whatever America would gain in its drive to sew up commercial contracts, it could lose much more outside of Iraq where anti-Americanism poses a potential danger.

To be sure, at this moment most American business executives do not seem to be overly concerned about anti-war feeling spilling over into their operations - at least officially. I recently talked to some who run American chambers of commerce in Germany, France, South Korea and Mexico. Typical of their comments was that of Fred Irwin, chairman of CitiGroup in Germany and president of the American Chamber of Commerce there. "I don't see any links between tensions between Washington and Berlin and attitudes of Germans towards American investors," he said. I also asked Secretary of Commerce Donald Evans what he thought about the link between popular opposition to US policies and attitudes towards US business. "We'll get past this," he said. "I don't think the geopolitical issues are going to have any long-term momentum."

Nevertheless, I also interviewed several American business leaders who did not want to discuss these matters on the record but who were much more cautious. Those working in Europe are most secure, although they have an eye on large and potentially restless Muslim populations. Those doing business in the Persian Gulf, in particular, but also in Asia, have deeper concerns which include an escalation of terrorism coming out of these regions. There is also some concern that if there is a backlash in the US against countries that criticize American behavior, then this could result in US boycotts that would cause foreign nations to retaliate.

The evolution of anti-American attitudes toward US companies might not be sudden or dramatic. We are unlikely to see massive boycotts of large numbers of American companies. But in nations where governments still have a say in the award of big business contracts, such as China and Saudi Arabia, fewer could go to American companies. In Europe, the best and the brightest local talent might shy away from working for US firms. American companies may find that the cost of physical security is a competitive disadvantage.

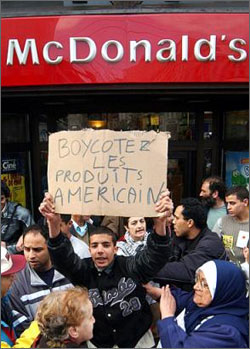

The most vulnerable businesses could be consumer product companies or other classic American icons. Just last week, the Wall Street Journal reported on antiwar protesters in Calcutta who attacked a shop owned by Nike. The story also described how Italian police defused a bomb outside the Bologna operations of IBM, and how customers of Wal-Mart in Germany, Argentina and Mexico have plastered anti-American posters in the stores' parking lots. Last week, too, the New York Times reported on how American companies like McDonalds in France were accelerating their drives to differentiate their menus and their store designs from their American parents. There is also a potential danger to companies where foreign competitors are most readily available and where the symbolism of being American is particularly high - companies like Boeing, which have rivals such as Airbus.

If overseas American business suffers, so will the US economy. Many US companies have become dependent on overseas markets for more than 30% of their revenues. American businesses have also become central to global supply chains that service the US itself; for example, over 25% of the products we import come from the foreign subsidiaries of US firms. At the end of 2001, American multinationals had invested over $2.3 trillion directly in foreign plans and facilities. Large as this sum may seem, we will never know the cost of American companies that decide not to invest abroad or not to expand existing operations abroad because of a perceived hostile environment overseas.

Three things worry me the most. First is the changing nature of anti-Americanism itself. Dominique Moisi, a highly respected French commentator on global issues, told me that there used to be widespread public resistance to what America did, but that today there is an objection to what America is. We should take this sentiment as an important warning about the complexity and depth of foreign antipathy towards the US. In contrast to the past, anti-Americanism today isn't propelled just by leftist politicians or intellectual elites but encompasses a broader spectrum of society.

Second, we could be seeing the rise of a huge counterforce to continued globalization. American companies have been in the vanguard on that, and were they to be attacked or otherwise impeded, so could the continued liberalization of trade and investment that they have been so identified with. As Professor Francis Fukuyama of John Hopkins University has written, there is a risk today that opposition to American policies could become the chief passion in global politics.

My third major concern is the potential breakdown in the American-led multilateral system itself - a system in which American foreign policy and its economic policy were in synch, and in which Washington's goals were supported broadly by so many other key countries. If the current paralysis of NATO and the UN Security Council is signaling an end to the post-WWII consensus about the role that the US is playing on the world stage, then over time, all bets may also be off when it comes to the prospects of American business.

Jeffrey E. Garten is dean of the Yale School of Management. His latest book is The Politics of Fortune: A New Agenda for Business Leaders.