Complexity Marks Asia’s Use of Social Media

Complexity Marks Asia’s Use of Social Media

MYANMAR'S opening to globalization is remarkable on many levels, but it is unique to have an entire population enter the world directly in the era of social media. The country’s telecom infrastructure remains painfully inadequate — a simple call via a landline can take up to an hour to connect — but this has not held back the people of Myanmar from following Asia’s exceptional embrace of social media. In Yangon, the proportion of mobile users with smartphones is well beyond most countries at its level of economic development. This comes in part due to the high cost of SIM cards: If you can afford a $2,000 SIM card, why not get a smartphone? From their smartphones, they use Facebook to connect with friends, Viber to make phone calls and Instagram to exchange photos. For many, there is no distinction between Facebook and “the Internet.” Myanmar may be the world’s first country to leapfrog the Internet straight into the era of social media.

Using the benefit of hindsight from social media adoption in other Asian countries, it is safe to predict that Myanmar will benefit in terms of education, accountability and transparency. There will also be challenges, most notably the risk of cyber-bullying and hate speech writ large through the incitement of violence against minority ethnic groups — a bloody problem the country already faces, as illustrated by the outbreak of deadly violence against the Rohingya and other Muslims throughout the Buddhist-majority country.

RAPID ADOPTION, VARIED USES

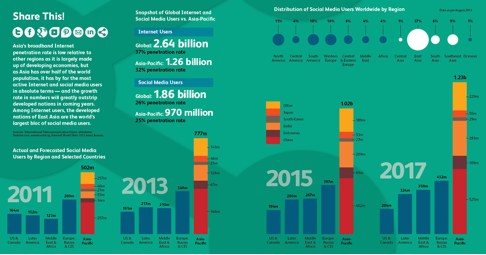

As in Myanmar, social media is not an afterthought in Asia. Fueled in part by the relative youth of populations and rapid economic development, Asia’s adoption and usage often outstrips other parts of the world.

The people and government of Myanmar would do well to learn from Indian ministers, who know that a badly worded tweet can end your political career, or from China’s central government, which knows that that even a non-democratic system must adjust policy in relation to social media conversations.

In Japan, tsunami rescue efforts in March 2011 were in part directed through Twitter. In one notable example, a grandmother stuck on the roof of her home in Japan managed to send out a single tweet read by her son in London, who told rescue services to dispatch a helicopter that picked her up on the roof, all within hours.

As with any sector, the growth of social media in Asia has played out against the region’s inherent complexities: different languages, cultures and levels of economic development. An additional wrinkle is that even countries of similar levels of economic development — Japan and South Korea, for example — use social media in radically different ways.

As Asians race to embrace social media, there are two distinct and ongoing battles.

The first is a Great Game-style fight between platforms for supremacy in the world’s fastest-growing region. Unlike Silicon Valley’s foundational myth of a startup in a garage, some of today’s fastest-growing social networks from Asia are local platforms backed by major corporations. The second is a struggle by governments and companies to understand how the platforms are being used and how they can benefit from this radical shift in communication.

SHIFTING ALLEGIANCES

The lines in the battle between platforms are drawn along technical and cultural parameters. Technical factors start with such simple elements as broadband access, but can also be related to seemingly small moves by social media companies that bring big impact. Indonesia, for example, was among the first countries to quickly adopt social networking platforms on a mass scale. Indonesians threw themselves initially into sharing and connecting on the Friendster social media site with such gusto that a new vocabulary evolved in Indonesian, and the Silicon Valley-based company reallocated resources from North America to serve the demand. This dominance evaporated, however, within a few months of Facebook launching a BlackBerry-based app in 2009.

Jakarta switched allegiance overnight to Facebook, with the rest of the nation quickly following suit. The key drivers were urban traffic and the high cost of home broadband. After buying a BlackBerry, often purchased in the grey market of items smuggled past customs, Indonesians could subscribe to a cheap mobile data plan. Additionally, the BlackBerry option meant friends could connect while sitting in Jakarta’s legendary traffic jams. By no means does technical bias automatically push users to the latest platform. Even as BlackBerry’s fortunes wane in the era of Android-based devices and the iPhone, BlackBerry messenger remains wildly popular in Indonesia through the downloadable app.

Another example of Asia’s proclivity to maintain legacy platforms comes in Taiwan, where some of the most lively online discussions take place on Telnet forums, a plain vanilla technology that came of age in the 1990s. Students plug into Telnet forums while attending the island’s top universities and maintain the habit well into their professional careers.

There has been a noticeable distinction between those countries where governments laid a strong physical Internet backbone, such as China or Vietnam, and countries such as India or Indonesia, where constraints imposed by limited landlines pushed many people to access the Internet by mobile phones first. Thanks to constraints in the physical infrastructure, India reached the crossover moment last year, with more people accessing the Internet via mobile phones than landlines.

While technical constraints impose varying challenges, culture also has a heavy impact on social media adoption. Culture came to the fore in Taiwan, for example, with the arrival of Facebook. Few in Taiwan saw the point of Facebook until Zynga launched the game Farmville. The game, in which users tend a virtual farm, required players to log in via Facebook. Gaming-obsessed Taiwanese joined Facebook to play, but to do little else. As a result, the number of Facebook accounts in Taiwan skyrocketed as those disappointed with their gaming scores signed on with a new identity. Facebook, whose underlying value remains the social graph of connections between people, found itself with a huge number of inactive accounts created for gaming. Eventually, Taiwanese users gradually began using Facebook as a social platform, leaving Facebook with the task of weeding out the dead accounts.

THE CHINESE WAY

For all the differences across the region, China stands out globally as the most unique social media market in the world. The combination of heavy government intervention, extreme levels of competition for a valuable market and the legacy of loneliness brought about by Mao Zedong’s one-child policy has created a unique social media dynamic. In addition, the high level of distrust of state-controlled media has pushed social media in China to become a primary conduit of trusted information. In many ways, the rise and decline of Sina Weibo, originally a Twitter clone, highlights many of the striking characteristics of China’s social media space. From its earliest days, the government had a major hand in Sina Weibo’s success. There were a number of Twitter clones launched in China at about the same time, but most were quashed by the central government. It is impossible to know for certain, but there was speculation that government officials felt Sina Weibo, launched by a large portal, could be better relied upon to reign in users than a small startup. As it gained traction in major cities, Sina Weibo became a citizen-journalist network, bringing attention to many hot topics, from corruption and the conspicuous consumption of government officials to giving voice to parents whose children had been affected by melamine-tainted milk powder. Responding to consumer demand, Sina Weibo evolved more rapidly than Twitter to include such features as picture sharing, video and even social networking functionalities. Now, Sina Weibo is moving into e-commerce by tying in with the payments system from online shopping site Alibaba.com.

A further element typical of China, hyper competition, means that less than four years since its ascension, Sina Weibo is now challenged in fundamental ways by WeChat, a social media platform built around more private sharing. It grew first in mainland China and has now gained traction in Hong Kong, Taiwan and a few markets outside of Asia. WeChat’s approach, sometimes called Instant Messenger 3.0, is a new, dynamic and highly competitive category of mobile phone-based social media, with its major competitor, LINE, also coming out of Asia. Unlike Silicon Valley startups, WeChat was launched by one of China’s largest Internet companies, Tencent, while LINE is owned by NAVER, one of South Korea’s dominant Internet companies.

To give the concept a monetary value, WeChat and LINE can be superficially compared to WhatsApp, the platform recently purchased by Facebook for $19 billion. The difference is that while WhatsApp has more global reach, WeChat and LINE have evolved much deeper offerings for their users. At a basic level, WeChat, LINE and WhatsApp all offer free SMS messages. By using Wi-Fi and data plans, these apps send short messages for free, allowing consumers to bypass the charges imposed by their telco carriers.

NEW REVENUE STREAMS

Where LINE and WeChat differ from WhatsApp are the ways in which consumers engage with each other and companies through the platforms. The first novel revenue stream from Japan for LINE came from selling colorful emoticons that users purchased to send to one another. WeChat gained early traction in Beijing in part thanks to “shake,” a functionality that allows users to see other WeChat users in the near vicinity who are also “shaking” their phones at the same time — a revolution for the dating scene.

From these early hits, both WeChat and LINE grew large user bases and converged around functionalities that appeal to both users for their convenience and companies for the connections they build. LINE’s links to consumers, for example, proved a powerful trigger when Lawson, the Japanese convenience store chain, offered a simple discount coupon. Redemption rates shot up in part due to a discount being announced on your mobile phone while you might be walking near a Lawson store. WeChat’s functionalities, which seem to grow by the day, include sending payments for a cab ride from the app to the driver, checking into flights and basic banking functions. From the perspective of companies, both WeChat and LINE now offer a new way to grow, maintain and nurture customers at scale.

UNDERSTAND SHARING

For some companies, the popularity and the functionality of these platforms have turned them into business tools to manage relationship with clients.

Customer Relationship Management, or CRM, had traditionally had been limited to those moments when a customer engaged directly with the company through contact with a sales person or website. Social media now allows consumers to tell companies about their interest in a product or service and open new moments for engagement.

A Chinese consumer connected on WeChat to a French luxury brand might be met upon landing at Charles de Gaulle airport with a personalized invitation on his or her mobile phone to visit the Paris flagship store to see a product about which they had enquired previously. Another element of customer relations in the era of social media is enabling those customers who fundamentally believe in a product to advocate on behalf of the company.

The lifeblood of advocacy is content that someone actually wants to share with a friend. Creating this content in ways that appeal to Asia’s diverse cultures is likely the next great challenge brought by social media. It may have been possible in a previous era to localize an advertisement through language and a local celebrity. Now, however, shared content is becoming a key driver of business, with the impact of content that has been shared by a friend far greater than that of a simple broadcast.

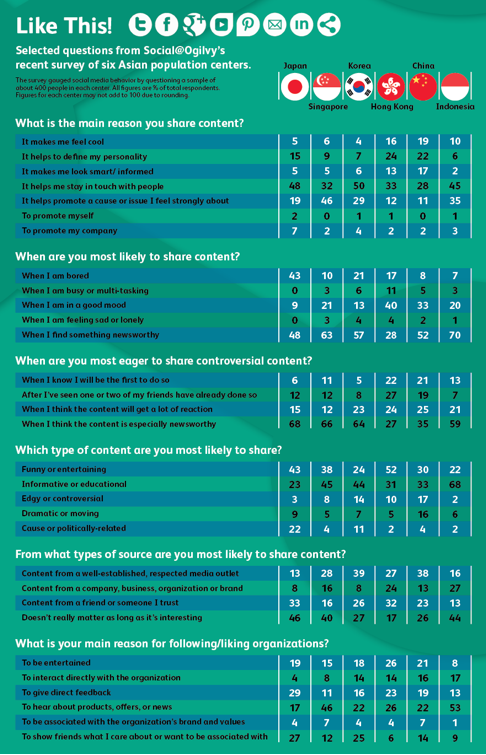

For a region with such a wild diversity of cultures, it is not surprising to see that the drivers behind sharing in Asia vary wildly. A recent study of 2,500 social media users in six Asia countries by Social@Ogilvy and SurveyMonkey found that companies risk failure at engaging potential customers on social media unless they adjust their strategies according to how consumers in various markets share.

The variance on sharing took place according to why people shared, what they shared and how they liked to share it (see charts). One example is the type of content that social media users in Asia like to share. There is a strong bias in Hong Kong toward sharing funny or entertaining content, for example, while in Singapore and Indonesia respondents said they liked to share informative or educational content.

Through looking at the spread of social media and the drivers behind content sharing, it is clear that Asia’s complexities run deep. In short, Asia’s widespread and rapid adoption of social media platforms — Facebook, WeChat, LINE and others — may hide but do not eliminate the region’s differences.

Thomas Crampton is global managing director of Social@Ogilvy at Ogilvy & Mather.