Containing the Fire in Syria

Containing the Fire in Syria

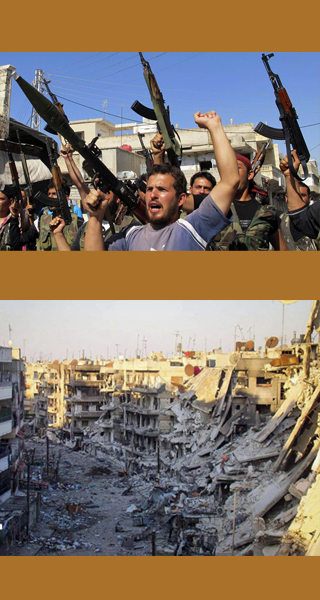

NEW HAVEN: The awful conflict in Syria grinds on, with more than 100,000 dead and no end in sight. The calls to “do something” – anything – become louder: arm the rebels, enforce a no-fly zone, send in the Marines. Before the United States acts, Americans should reflect on the realities in Syria in a historical context. Here are some relevant dates and events.

Syria, February 1982: The Assad regime corners the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood in Hama, the country’s fourth largest city. For the minority Alawite government, an offshoot of Shia Islam, the fundamentalist Sunni Brothers are an existential threat. Assad rings the city with armor and artillery, and methodically destroys its center. The Brotherhood is largely eliminated, along with more than 10,000 Sunni civilians. The regime knew that the day of revenge might come and spent years developing the security, intelligence and military apparatus to deal with it.

Lebanon, summer 1982: The Israelis invade Lebanon with twin targets – the Palestine Liberation Organization who control the south and the Syrian Army in Beirut and the Biqa’ Valley. Both are forced to evacuate Beirut, the former by sea under the eyes of US Marines, whose presence was a Palestinian condition against any action by the Israeli military during withdrawal. Days after the Marines’ withdrawal, the Israelis and the Lebanese Force – a Christian militia – enter west Beirut. The latter perpetrate a massacre of Palestinian civilians in the Shatila refugee camp. The cry to “do something” goes up in Washington, and the Marines are returned on an undefined “mission of presence.” Meanwhile, Syria and the new Islamic Republic of Iran forge a strategic alliance and create Hezbollah, an alliance and a militia that figure prominently in the conflict today in Syria. For the US, the consequences were catastrophic. April 1983 saw the bombing of the American Embassy and the greatest loss of embassy officials in the history of US diplomacy. Six months later, the Marine barracks were bombed with the largest loss of Marine lives in a single attack in the history of the corps. I was there for both.

Lebanon/Syria, June 2000: Israeli forces withdraw from Lebanon under intense pressure from Hezbollah, backed by Syria and Iran. Hafiz al-Assad dies and is succeeded by his son Bashar. There was a naïve expectation in the West that because he did postdoctoral studies in the UK and knew how to use a computer he would move to westernize Syria. As ambassador to Syria then, I knew him and knew he would not. He was more rigid and doctrinaire than his father.

Iraq, March 2007: I arrive as ambassador and find a situation eerily similar to the one I survived in Lebanon a quarter of a century before. Iran was supporting radical Shia militias that resembled and, in some cases, were trained by Hezbollah to fight the US-led coalition in the east while Syria facilitated the transit of Al Qaeda operators who joined with Iraqi Sunni militants to fight in the west. Iran and Syria used these tactics to drive us out of Lebanon; it nearly worked in Iraq as well.

There are many other examples of Syrian-Iranian coordination and the utter ruthlessness of both states in pursuing their objectives, such as the 2005 assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri. During my time in Lebanon, we had a dark joke about “Hama rules,” meaning there were no rules governing Syrian conduct.

So this current fight didn’t start in the southern Syrian city of Dara’a in 2011. Nor is it part of the so-called Arab Spring. It began decades before. Lebanese, Palestinians, Iranians, Jordanians, Iraqis and Syrians – Sunnis, Alawis, Christians and Druze – all remember. Americans may not have ever really understood it in the first place. The history helps explain the ferocity of the fight on the part of both the regime and its opponents, and it illustrates why this regime is not like those in Egypt, Tunisia or Libya. It was ready for this war.

The opposition, in contrast, lacks cohesion and organization. As is often the case in these conflicts, the most radical elements demonstrate the greatest discipline such as Al Qaeda in Syria – Jabhat al-Nusra. It is what makes arming the opposition such a dangerous and uncertain proposition. Weapons intended for relative moderates such as the Free Syrian Army may well be seized by the radicals who are gaining ground against other opposition elements. But the arms are flowing, reminding us this is a proxy regional war as well as a vicious conflict in Syria. Iran will do everything in its power to see that its single Arab ally for more than three decades does not fall to a virulently anti-Shia opposition. Hezbollah has been a formidable element in the regime’s order of battle. Saudi Arabia and Qatar, on the other hand, see an opportunity to weaken Iranian influence in the region and are pumping arms to the opposition. Who gets them and to what end is another question.

Much has been said about a political settlement. The conditions are simply not present. Neither the opposition nor the regime is ready to deal seriously with each other, and the opposition is too divided in any event to develop a coherent position. Nor will a meeting between regime representatives and opposition elements in exile produce meaningful outcome, even if it could be convened. The influence of the exiles on those actually doing the fighting is approximately zero.

So what are the options? First, to recognize that as bad as the situation is, it could be made much worse. A major western military intervention would do that. And lesser steps, such as a no-fly zone, could force the West to greater involvement if they proved unsuccessful in reducing violence. The hard truth is that the fires in Syria will blaze for some time to come. Like a major forest fire, the most we can hope to do is contain it. And it’s already spreading. Al Qaeda in Iraq and Syria have merged, and car bombs in Iraq are virtually a daily occurrence as these groups seek to reignite a sectarian civil war. The United States has a Strategic Framework Agreement with Iraq. We must use it to engage more deeply with the Iraqi government, helping it take the steps to ensure internal cohesion. This was a major challenge during my tenure as ambassador, 2007-2009, and the need now is critical.

I was in Lebanon recently, where the outgoing prime minister gloomily predicted a renewed civil war of which there are already signs with clashes between Sunnis and Alawites in the northern city of Tripoli, in the northeast and attacks on Hezbollah-controlled areas in Beirut. If the violence spreads, the Palestinians will join forces with the Lebanese Sunnis against the Shia, and that in turn will radicalize Palestinians in Jordan’s already fragile monarchy. Both countries need our security and economic support, for the refugee influx and their security forces.

This will be a long war. There is little the United States can do to positively influence events in Syria. Our focus must be on preventing further spillover beyond its borders. There may come a point where exhaustion on both sides makes a political solution possible. We are nowhere near that point. And my fear is that at the end of the day, the Assad regime prevails. We must be ready for that too.