Coping with World Population Boom and Bust – Part II

Coping with World Population Boom and Bust – Part II

Today, in one country out of three, fertility is below two children per woman, the level necessary to ensure stable population numbers, or, in the term preferred by demographers, the 'replacement' of generations. In some countries, such as Armenia, Italy, South Korea, and Japan, average fertility levels are now closer to one child per woman.

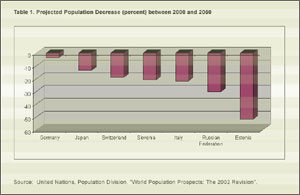

In the absence of immigration, when fertility remains below the two-child replacement level long enough, a population shrinks and ages. This is the projected future for most low-fertility countries. In a couple of generations, for example, the Italian population is projected to be 20 percent smaller than it is today, with the working age population (15-64 years) shrinking by some 40 percent. It is not difficult to imagine the social and economic consequences of such a drastic change.

The picture for Europe as a whole is not much different than Italy’s. By mid-century, Europe’s population is projected to be 13 percent smaller, with the working age population declining by 27 percent, and the median age increasing by a third, reaching 50 years. Population decline and aging is also in the future for Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. In contrast, Australian and Canadian populations, which also have below-replacement fertility levels, and the United States, which has fertility near replacement, are expected to continue growing throughout the century – a trend due largely to immigration.

Many governments view low birth rates, with the resulting population decline and aging, to be a serious crisis, jeopardizing the basic foundations of the nation and threatening its survival. Economic growth, defense, and pensions and health care for the elderly, for example, are all areas of major concern.

While population decline has been an issue in the past, today’s concerns are more widespread, involving virtually all regions of the world. Also, these concerns have extended over a lengthy period of time, and consequences have become progressively evident to governments as well as the general public. In addition, the problem of below-replacement fertility is spreading rapidly.

Why are birth rates falling? With expanding opportunities for higher education, careers, and economic independence, combined with highly effective contraception, young women are postponing – or altogether avoiding – motherhood. In many parts of Europe, for example, more than 10 percent of women in their early forties are childless. In Finland, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, the number approaches 20 percent.

Moreover, for women choosing to have children, the average age at first birth has risen in most low fertility countries. Today, that average is in the late 20s, with many women having their first child in their early 30s. Postponing the first birth often translates into fewer subsequent births. The end result: an average family with fewer than two children.

The responses governments can take to raise fertility rates closer to replacement levels may be grouped into seven broad categories. The first category relates to restricting or limiting access to contraception and abortion. While most countries have policies regulating the use of contraception and abortion, however, few governments are prepared to ban their usage in order to raise fertility levels.

A second category of options focuses on limiting the education of girls, employment of women, and the broader participation of women in society. Here again, few, if any, countries are prepared to take such steps in order to encourage childbearing.

A third set of measures centers on promoting marriage, childbearing, and parenting through various means, including public relations campaign and matchmaking services. Many public relations campaigns promote the vital role of maternity and motherhood, stressing that women are making a valuable contribution to the welfare of the family and societal development. These campaigns have been especially prominent among a number of East Asian countries, including Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. For example, a recently launched campaign by the South Korean government has the slogan: “Let’s Have One More Kid”. The most recent example comes from Singapore, where the government launched a drive to give a package of incentives for child birth.

A fourth category of pro-natalist measures aims at transferring some of the costs and activities related to childbearing and childrearing from the parents to the larger community. Examples of these policies include cash bonuses and/or recurrent cash supplements for births or dependent children, infant and childcare facilities, and pre-school and after school care facilities. Recently, payments of cash bonuses for the birth of a child (or additional child) have been popular in such countries as France and Italy, at 800 Euros and 1,000 Euros, respectively.

A fifth set of policies aims primarily at helping women balance work and family responsibilities. These include maternity leave, part-time work, flexible working hours, working at home, and nurseries and day care at the office. In addition to the financial costs, such measures are often difficult to implement, due to resistance from employers as well as the reluctance of some women to interrupt their careers.

In parallel, a sixth category of policies is aimed primarily at men. These policies are intended to increase the involvement of men in activities that have been traditionally considered the realm of women (e.g., parenting, family maintenance, and household chores). Although these measures include paternity leave, the principal emphasis of this category of measures is to encourage husbands to share in the rearing of children. Here again, such policies are difficult to implement, both for economic and cultural reasons, especially among countries where gender roles tend to be more rigidly defined.

A seventh category of policy measures centers on financial, political, and legal preferences to couples with children. This includes granting parents priorities or assistance in securing mortgages, loans, low cost or subsidized housing, welfare assistance, increased pensions, government services, and benefits. More recently, some governments are considering changes in the political system in order to be more responsive to the needs and concerns of couples with children. For example, granting extra voting rights to the parents of minor children, as is being discussed in Austria, may provide an opposing counterweight to the increasing political strength of elderly voters.

Will government policies, incentives, and various other pro-natalist measures be sufficient to raise birth rates to replacement levels? Taking into account the considerable social, economic, and political constraints, the policies most governments will be able to offer may have only a modest – and temporary – effect on raising fertility. It also seems likely that fertility may increase somewhat above the very low rates of today as the lowering effect of postponing childbearing runs its course over the coming years.

Nevertheless, current and foreseeable efforts available to most governments to raise their fertility rates seem highly unlikely to succeed, at least for the near term. In other words, a government appeal to Sweetie to have a baby is unlikely to reverse the trend any time soon – even with a little sugar on it.

Joseph Chamie is the Director of the Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations.