Crunchtime for Global Tax-Avoidance Push

Crunchtime for Global Tax-Avoidance Push

Nearly 50 governments are set to agree this fall to a new set of rules to clamp down on tax avoidance among multinational corporations. Their chance of success, however, is unclear.

If the rules work as planned, they will help ensure big companies pay tax on profits where they are earned, boosting revenues for governments, particularly in larger countries. Advocates say the stricter rules will make for fairer competition between small and large companies, since the latter gain an advantage by being better able to avoid tax.

Far less certain is how widely the new rules will be applied, and whether they will boost government revenues after all. Also unclear is whether the U.S. will overcome opposition in Congress, where critics question the Treasury Department’s right to implement international rules not reflected in U.S. legislation.

The international effort was launched in 2012 as governments struggled to contain a surge in deficit-spending that followed the financial crisis and the global recession.

Amid burgeoning deficits, a string of revelations about large-scale tax avoidance by a raft of big companies emerged, and officials turned attention to the web of thousands of tax treaties dating back to the 1920s.

These treaties were initially intended to prevent the double taxation of company profits. But over time they became a playground for companies engaged in what tax people like to call Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, or BEPS, a term of art for moving profits to the jurisdictions with the lowest taxes.

The new rule book, hammered out under the direction of the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, will be presented to finance ministers from the Group of 20 largest economies in October. With approval all but assured, it will then go for a final review by G-20 heads of state in November.

The principle underlying the new rules is that profits should be taxed where they are generated, rather than where they attract the lowest tax rate.

“Tax planning will continue, but we are closing down the large avenues,” said Pascal Saint-Amans, director of the OECD’s Center for Tax Policy and Administration, who has overseen the BEPS project.

It won’t be easy work.

Identifying exactly where profits are generated is complex, and has become only more so as supply chains become more global. A product that ends up on a shelf in Germany or the U.S. can contain components manufactured in a dozen other countries, and include intellectual property in the form of patents, licenses and brands from still others. Those intangibles can in turn be housed practically anywhere, including in a small office in a low-tax jurisdiction.

For that reason, those involved in the BEPS project believe its main achievement is a requirement that companies declare the amount of revenue, profit and tax paid in each country, as well total employment, capital and assets used in each location. That would give tax collectors a clearer idea of how much profit is generated at each stage of the production process.

In addition to being costly to comply with, country-by-country reporting has raised concerns among multinational companies that the information could leak into the wrong hands.

Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R., Utah) and House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R., Wis.) have joined in the pushback. The benefits of providing sensitive corporate information to other countries are “unclear, at best,” they wrote in a letter last month to Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew.

Observers of the talks say efforts to amend the new rules by legislators around the world would slow their implementation, and threaten to make the rollout less comprehensive and coherent than their designers intended.

“The general sense is that people are unsure how much key governments are willing to implement it,” said Francesca Lagerberg, an international tax expert at business-services firm Grant Thornton. “A lot of countries will look to the American lead to see how committed they are.”

At the OECD, Mr. Saint-Amans said the ambition is not to harmonize tax rules, but to set international standards that will “have a real influence.” It’s not essential, in other words, that every government backing the new standards succeeds in implementing them.

“The way all this has been designed is that if you have one country refusing, others are able to protect their tax bases,” he said.

The other big unknown about the new rules is how much additional revenue they would bring in.

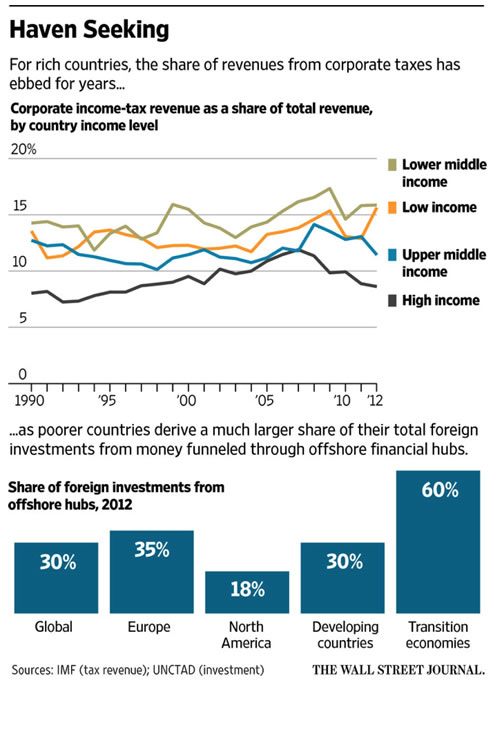

The OECD is set to provide an estimate for the scale of global tax avoidance on Oct. 5. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development concluded in June that businesses avoid paying $200 billion annually in taxes just by channeling their overseas’ investments through offshore financial hubs. Economists at the International Monetary Fund in May estimated lost tax revenues are equivalent to 0.6% of gross domestic product in developed economies and 1.75% of GDP in developing economies.

Those sums are large enough to give governments an incentive to clamp down on avoidance. Whether all of them will be able to remains to be seen.

Paul Hannon is a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.