Dealing With Disasters in a Connected World

Dealing With Disasters in a Connected World

SAN FRANCISCO: Natural disasters have struck since the earth’s beginning, but one dramatic change is underway: A global telecommunication network and the internet’s social media have shrunk the world, speeding news about any disaster as well as speeding delivery of succor for victims.

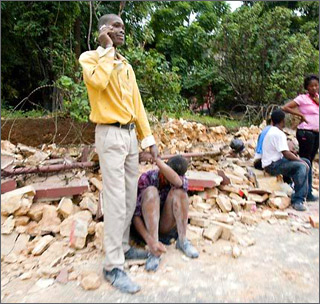

News of recent massive earthquakes in Haiti, Chile and China first arrived on other shores not as television video or professional news bulletins, but as amateur reports and images sent by cell phone and internet. Further expansion of the global electronic network, keeping it censorship-free, would contribute to improved worldwide response to future calamities.

Response to the deadliest 20th Century earthquake, which killed at least 240,000 people in Tangshan, northern China, reveals how much has changed: News of the July 1976 earthquake reached China’s central government after a coal miner named Li Yulin drove an ambulance six hours to Beijing. Although seismologists around the world knew that something big had happened in China, the secretive Chinese government, then in the throes of political succession, did not formally acknowledge the quake’s massive destruction until three years later.

This year, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake devastated the Port-au-Prince region of Haiti on January 12 – killing an estimated 222,570, injuring 300,000, and displacing 1.3 million, according to the US Geological Survey. On February 27, an 8.8-magnitude earthquake striking near Concepcion, Chile, killed nearly 1000. And on April 13, a 6.9-magnitude quake in remote Quinghai, China, killed at least 2,183 people.

News moved as fast as electronics and telecommunications could carry it. Social media replaced pornography as a preferred destination for internet users in 2008 and now serves as the earliest news source for any major event, from political upheavals to natural disasters.

Rapid response to the quakes, including targeted fundraising and more effective relief, boosted the status of social-media sites. Ordinary people use electronic media’s global reach reach to spread news and raise money for rescue and relief; rescue and relief workers communicate with one another, the displaced connect with family and friends, and onlookers deliver messages of comfort. Even scientists at the US Geological Survey examine social-media volume and topics for extra data on shaking, surface movement and damage.

Governments tempted to censor social media for any opposition would do well to ponder the overall benefits of free information flow.

As recently as two decades ago, natural-disaster assistance could take days to arrive, as news traveled by messengers on foot or vehicle, and later by telegram, telephone calls, fax, and rolls of film packed in lead-lined pouches transported by plane. For this year’s quakes, UNICEF, the Red Cross and other NGOs launched relief campaigns in less than 24 hours.

As government and non-governmental agencies converged on the devastated regions, relief workers used email, texting and social media websites to communicate. Social media technicians in the US and Europe worked around the clock to adapt websites and messaging applications to the needs of each community on three continents.

"Telecom is not a luxury in emergency response,” said Paul Margie, US representative of Telecommunications Without Borders, based in France, in an interview aired on The World radio program. “It’s core to the mission.”

Survivors, relatives and friends, both inside Haiti and outside, searched for one another using Twitter, Facebook and YouTube – all free services. Devastated electric grids or smashed computers are not obstacles so long as mobile devices still work.

Emergency-relief organizations raised millions of dollars using social-media networks. Responding to social network appeals, cell phone users raised $25 million for the Red Cross in two weeks by texting “Haiti” to 90999 and adding $10 to telephone bills.

Facebook, which began in 2004 at Harvard University to connect students with “friends,” today claims more than 400 million “active users,” and 100 million of those access the site with mobile phones and devices. Some 70 percent of Facebook members are outside the United States.

Twitter, launched in 2007, allows users to upload brief texts, or “tweets,” no more than 140 characters, which can be read online or passed among mobile devices of “followers” who sign up for user messages.

Twitter became a fundraising tool for the celebrity concert Hope for Haiti Now, broadcast internationally on January 22. The concert website tracked tweets on a world map – and the map still lights up every few seconds with new tweets from around the globe.

Twitter is available in six languages and 60 percent of its registered users are outside the United States. Before January 12, the Red Cross Twitter account had been adding up to100 followers a day. During the week after, the account added at least 10,000 followers. After Chile’s February 27 quake, the fifth largest in recorded history, Twitter signups spiked 1,200 percent, nearly all using Spanish, according to Twitter's blog.

YouTube, a website started in 2005 for sharing videos, boasts more than 1 billion views a day. Millions of hits show that users watched thousands of videos on Haiti’s disaster and recovery – and news programs relied on these as well. Not long after the Chile quake, a “Hope for Chile" video was posted, accompanied by a social-media campaign to raise relief funds.

In addition, mapping websites, such Ushahidi and Crisiscommons.org, used graphics to indicate emergency needs, and searching for people using Google, Yahoo and other search engines gave searchers immediate access to phone numbers, addresses and other details.

International telecommunications may even have saved the life of one Canadian man, who sent an SOS text from his mobile device to the Canadian Foreign Affairs Department in Ottawa, saying that he was alive, awaiting rescue beneath a collapsed building in Port-au-Prince.

Still, a closer look at social media’s role after these earthquakes suggests that gaps remain. Border-spanning power of electronic social media has not overcome human nature. Some Twitter messages from Haiti carried rumors, and the FBI issued warnings about charlatans requesting funds via Twitter messaging.

Nor have social media bridged the digital divide: Haitian internet use was low before the earthquake, and many Haitians still rely on radio and word of mouth for news.

Social media websites work best where used the most. After the Qinghai quake, Chinese names entered into Google produced little useful information. Google still struggles with nations, particularly China, over how much information should be made available online.

Although China has opened remarkably since the secretive 1970s, it continues to try and repress information that challenges emergency response.

In 2008, a 7.9-magnitude quake rocked Sichuan province, killing almost 90,000 people, including many children in collapsed schools. Critics of shoddy building practices and the post-quake government response were harassed and even jailed.

Again and again experience of recent disasters has shown the difference fast and uncensored communication makes to the survivors and relief workers. Social-media responses to natural disasters will accelerate only as long as telecommunications remain fast, cheap and uncensored.