Democracy Gains in Southeast Asia’s Islamic Nations

Democracy Gains in Southeast Asia's Islamic Nations

JAKARTA: Western media and government often mistake Al-Qaeda-inspired terrorism for Islam's disavowal of democratic order. Osama bin Laden's anti-American screed seems to reinforce such a mistake. And yet, a democratic order is in the making precisely where the largest Muslim societies in the world live - Malaysia and Indonesia.

In Malaysia, a multiracial and multi-religious political grouping, Barisan Nasional, celebrated a landslide victory after the March election. Faring much worse at the polls, the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), a party advocating the adoption of Islamic law, or Sharia, was forced to acknowledge defeat.

In Indonesia, the story is not entirely different. The April 2004 election results indicate that while a political party with an agenda similar to PAS gained more seats in the national parliament, its influence still remains marginal; once the final tally is clear, probably only 25 percent of the parliament seats won by the Prosperity and Justice Party will be attributed to pro-Shariah voters - a figure not far above the 16 percent figure cited in the 1999 parliamentary election.

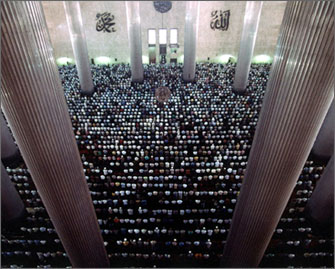

Of course, this is by no means a setback for Islam as a social presence.

In Malaysia, Islam remains the national religion, and it is still an essential part of most people's identity. Even in a cosmopolitan city like Kuala Lumpur, Muslims take great care to observe their religious duties publicly. Most Muslim women wear the required headscarf, and during the fasting month of Ramadhan, the police ensure that Muslims refrain from eating and drinking in public places. Each year, thousands of people go to Mecca for the hajj. And yet, it does not mean the faithful will automatically follow the 'revivalist' agenda.

The 'revivalists', often called in the Western media as the 'fundamentalists', advocate a return to the putative 'origin' of the faith and the establishment of 'Daru'l-Islam' (The Abode of Peace), a perfect future more or less equal to the Christian idea of 'the city on the hill.'

In Malaysia, the 'revivalist' ideas have a visible influence in society as well as in state policies, without making Malaysia an Islamic state like Iran. In Indonesia, the Muslim version of 'the city on the hill' is more blurred. Despite the fact that this is the largest Muslim country in the world (about 87 percent of its 220 million population are registered as Muslims), Islam has never been declared the national religion.

Resistance to establishing a national religion is deeply rooted in Indonesia's political history. In 1945, when drafting the constitution, leaders of Indonesian nationalist movement overruled any suggestion to prioritize 'Islam'. The founders of the new nation decided not to disturb the plurality of faiths and cultures - multiple Muslim sects as well as Christians and Hindus. Still, despite its refusal to adopt Islam as the country's legal foundation, Indonesia does not want to be known as a 'secular' state.

Indonesia's ambiguity as an Islamic state may be due to three separate dynamics. One is the trauma of violence. As early as 1946, 'Darul Islam', a militia group opposed to the new republic, advocated the creation of an Indonesian 'Islamic state'. The ensuing guerilla actions between Darul Islam and the government destroyed much of the West Java rural society. The rebellion was ultimately squashed after two decades of violence. A similar armed conflict took place in South Sulawesi from the 1950s until the 1960s. Consequently, any idea of an 'Islamic state' provokes fear of instability.

The second dynamic relates to Indonesian racial identity. In Malaysia, to belong to the racial category 'Malay', is to be 'Muslim'; in Indonesia, such identity formation does not exist. Racial categories, introduced by the Dutch at the end of the 19th century, are not aligned with religious grouping. An Indonesian 'Malay' can be a Christian or a Hindu. Many Indonesians of Chinese background are Muslims; in fact, Raden Patah, the first Muslim king in Central Java in the 15th century, was reportedly of Chinese descent. As follows, Islam plays out separately from racial identity politics - and this may reduce its role in race-based conflicts in Indonesia.

The third dynamic is that of plurality. In spite of its enduring presence, Islam in Indonesia finds itself on the defensive, no longer the sole guardian of truth and justice. Despite its prominent visibility in social life, Islam is not as cohesive as it is in, say, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries. Since its arrival in Indonesia in the 15th century, Islam has had to navigate among a plurality of religious interpretations, even within a single faith.

The plurality of discourse explains the emergence of liberal interpretations of Islam. One of the earliest and the most articulate spokespersons of this interpretation is Nurcholish Madjid. Educated at traditional Islamic boarding school in East Java, and holding a PhD from the University of Chicago, Nurcholish has a unique interpretation of Sharia. Sharia, according to Nurcholish, resembles the word 'way', implying process and thus continuation rather than inertia. The key notion is 'towards' (menuju), and we all are always on the way towards God, the unreachable, because He is absolute, and humans are not. For Nurcholish, islam means 'a complete submission to God.' Therefore all true religions are 'islam', and even the religion brought by Prophet Mohammed is not a unique, isolated, or separate entity. When one speaks of the 'triumph of Islam', Nurcholish says, "it should be the triumph of an idea, regardless who does the good work. The triumph of Islam should be happiness for all."

To be sure, the 'revivalists' will continue to provide a powerful challenge to such ideas. But at this point, their political impact remains uncertain, particularly on the issue of making Islam the legal foundation of Indonesia.

Indonesia's latest amendment to the constitution in the wake of the 1999 election reaffirmed the 1945 position described above - a significant phenomenon, considering the number of political parties emerging from powerful Muslim communities that won most Parliamentary seats. Interestingly, most of these Islamic political parties opted for 'pluralism'. The National Awakening Party rejected the idea of adopting Sharia law in the new constitution. The National Mandate Party, led by the former chairman of Indonesia's largest reformist Muslim organization, openly accepts non-Muslims in the party's list of leadership and legislators.

It is true that since the fall of Suharto many sub-provincial administrations have taken advantage of the government push to decentralize and tried to adopt Sharia law in their territories. But the general public still appears unwilling to have the government institute Islam as the national religion. In 2002, a survey was conducted to determine the extent of public response to the idea of applying Sharia law in Indonesia. The majority of the respondents supported it - and yet refused to have the government control their religious life. In their analysis for Journal of Democracy early this year, Saiful Mujani and R. William Liddle describe the survey's further findings. "A solid majority (65 percent) takes a neutral stance towards Islamism," and "only 14 percent of our Muslim respondents may reasonably be labeled as either strong or moderate Islamists." The remaining 19 percent is opposed to Islamism.

The Al-Qaeda-inspired bombings in Bali and Jakarta helped foster an image of Indonesia as a country teeming with radical Islamists. The reality, however, is that the world's largest Islamic nation hews firmly to a moderate course as it seeks to build a democratic order.

Goenawan Mohamad is a Jakarta-based writer and poet and former editor of the news magazine Tempo.