Desperate Migration in the Middle East

Desperate Migration in the Middle East

NEW YORK: A complex and troubling humanitarian crisis challenges the people and governments in North Africa, Western Asia and Europe – the desperation migration of growing numbers of refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons. The migration erodes the economies, social fabric, security and administrative capacities of most of the countries in a volatile region with consequences spilling into Europe, especially through illegal, hazardous migratory flows that too often result in the tragic loss of human lives.

Most of the persons forcibly displaced in the Middle East are the result of the civil wars in Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen as well as from the long-running Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In addition, tens of thousands of additional desperate migrants are arriving in North Africa from countries beyond the region. Growing numbers of migrants from Africa, especially from the Sahel region, notably Eritrea and Somali, and South Asia, particularly from Afghanistan, are traveling treacherous routes in hopes of being smuggled to the safety and opportunities offered in Europe. In 2014 more than 219,000 illegal migrants crossed the Mediterranean into Europe from North Africa, with an estimated 3,600 perishing at sea. An estimated 1,250 migrants drowned during April trying to reach Europe.

Worldwide the numbers of refugees have increased markedly in recent years. In the mid-20th century an estimated 1 million people remained uprooted from their homes. Latest estimates for the end of 2014 put the global number of refugees of concern to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, at close to 20 million. An additional 5 million Palestinian refugees are registered in about 60 camps in the Middle East administered by the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, or UNRWA. The number of people forced to flee their homes due to conflict has reached a record 60 million – 20 percent more than the previous record set in 2013, the first time since World War II that the total exceeded 50 million.

Contributing to the surge of forcibly displaced persons are enormous numbers of refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced people in the Middle East. The number of registered Syrian refugees, for example, soared from around a half a million at the start of 2013 to more than 4 million today, overtaking Afghans as the world’s largest refugee population aside from Palestinians. Also, the number of internally displaced people in North Africa and Western Asia, currently estimated at nearly 12 million, is more than five times the figure in 2005.

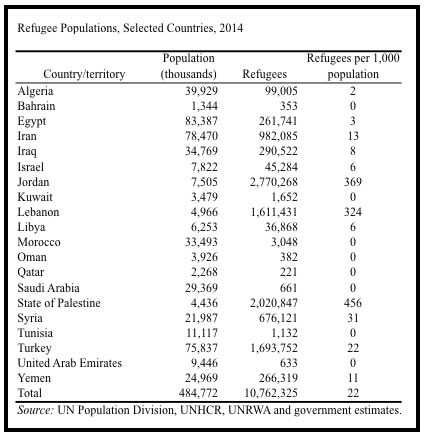

Estimates for 2014 indicate that the Middle East countries with the largest numbers of refugees are Jordan at 2.8 million; State of Palestine, consisting of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, 2 million; Turkey, 1.7 million; Lebanon, 1.6 million; and Iran, close to 1 million.

Aside from the wide-ranging impact of the Palestinian refugees, this refugee crisis has greatly burdened Lebanon, which by end of 2014 received 1.2 million Syrian refugees, and Jordan, which received 673,000 Syrian refugees. The ratios of refugees per 1,000 population in Lebanon and Jordan are in excess of 300 – about one-third of their resident populations are refugees. In striking contrast, the ratios of refugees per 1,000 population in European countries are a small fraction.

These totals are at least a year old, and corresponding figures for 2015 will be substantially larger. In Turkey, for example, the number of refugees, about 825,000 in mid-2014, is estimated to have more than doubled, mainly due to rapid influx from Syria. Similarly in Iraq, a current estimate of the number of internally displaced people is about 50 percent greater than the figure for mid-2014.

In general, government responses to the challenges posed by the huge numbers have been considerable and admirable. Yet the many services needed by refugees, including food, shelter, clothing, health care, schooling and safety, overwhelm governmental capacities and undermine public support, especially in refugee-weary Lebanon and Jordan. With gainful employment and proper schooling difficult to obtain, refugees are often hard pressed to establish a semblance of normalcy.

Demographic composition of recent refugees differs from the typical native population in the Middle East. The refugee populations are made up of more children and women compared to the population of the origin countries. More than half of Syrian refugees, for example, are under age 18 compared to about 40 percent of the pre-war Syrian population.

International agencies, charities and non-governmental organizations have assisted in addressing the crisis despite political chaos and security challenges. Some responses to the crisis are worrisome. Countries like Israel, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have placed legal obstacles and physical barriers preventing entry of asylum seekers and refugees as well as returning them involuntarily to their homes or to third countries. A recent EU initiative to thwart illegal migration across the Mediterranean is to identify, capture and destroy vessels before they’re used by smugglers, a possible violation of Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that states: "Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country."

By and large, governments and electorates are loath to accept large numbers of people in great need, who are ethnically different and may pose threats to social stability. Most prefer fewer foreigners crossing their borders given economic uncertainties, record government deficits, high unemployment, growing anti-immigrant sentiment and concerns about national and cultural identity.

Identifying realistic solutions is a daunting task. While ending the internal and cross-border armed conflicts is clearly a pre-condition for resolving the crisis, reconciliation among the warring groups seems unlikely in the near term. Additional humanitarian resources and financial aid is needed to assist Lebanon, Jordan and other countries burdened with millions of numbers of refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons.

One proposal often suggested is to ease the path for asylum seekers and refugees so they can enter Europe in a safe and responsible manner. Besides being objectionable to many Europeans, a major shortcoming of this proposal is the increasing difficulty in differentiating asylum seekers in need of international protection from economic migrants seeking higher wages and a better standard of living and migrating militants who wish to do harm.

Another proposal to address desperation migration is to increase levels of legal migration. However, doubling, even tripling, current levels of legal immigration to Europe would unlikely reduce illegal flows due to the huge numbers of potential migrants, particularly unskilled youth. Over the next generation, for example, the populations of countries in North Africa and Western Asia are projected to increase by roughly 50 percent. The African continent’s billion-plus population is expected to double.

Concerning the millions of refugees, three solutions exist in principle: repatriation to home countries; integration into their current country of refuge; and resettlement to a third country. Repatriation for many is unrealistic at least for the near term considering the raging conflicts. Local integration also appears to be problematic, especially in countries such as Lebanon and Jordan, given the huge numbers, limited employment opportunities, domestic demographic considerations and destabilizing political repercussions. Most refugees and receiving nations would prefer a return to their homes.

Consequently, the status quo remains the most probable course of action for the immediate future. However, following lengthy periods of worsening living conditions, international aid and local resources not keeping up with demands, growing resentment in burdened host countries and discouraging prospects for returning to their homes, increasing numbers of refugees, asylum seekers and others will attempt to reach Europe and other safe havens by any means possible, including being smuggled across treacherous and life-threatening routes.

Joseph Chamie is a former director of the United Nations Population Division.

UNHCR reports on the refugee crisis in the Middle East and Northern Africa.

Comments

no