Despite Effort, Peru’s Covid-19 Response Fails

Despite Effort, Peru’s Covid-19 Response Fails

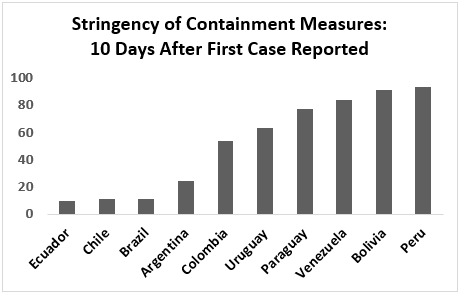

NEW HAVEN: In March, Peru was among first Latin American countries to introduce containment measures in the region, imposing the most drastic quarantine. International media celebrated the country taking such radical measures, especially given its capacity to launch ambitious fiscal and poverty alleviation policies to balance the economic impact of the containment and secure compliance on social-distancing measures.

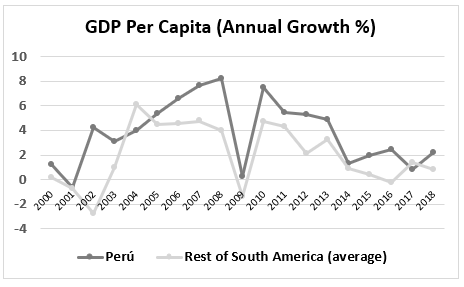

Following that line, some argued that “three decades of fiscal discipline and low public debt,” along with steady economic growth, put the country in an advantaged position relative to its peers, not only to spend those resources in the face of a crisis, but also to secure access to favorable credit lines from multilateral organizations. In other words, austerity measures were assumed to be responsible for Peru's favorable position.

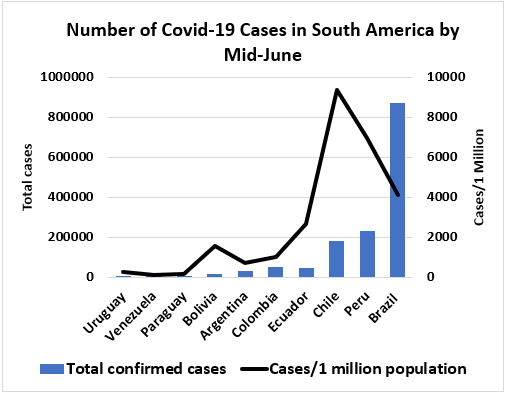

Nonetheless, three months later, media outlets report the failure of these measures, stressing the existence of a paradox between the intensity of the containment measures and the virus’ rapid spread among the population. Public health experts and economists highlighted four conditions that explain this paradox: the number of tests, the irregularity of the quarantine, the presence of crowds in markets and banks, and the level of overcrowded housing.

Due to the wide range in test availability, the comparative picture is imperfect. Peru ranks second in terms of tests for the region, yet public health experts agree that evolution of the country’s infection rates is still incongruent with what would have been expected, considering Peru’s stringent response.

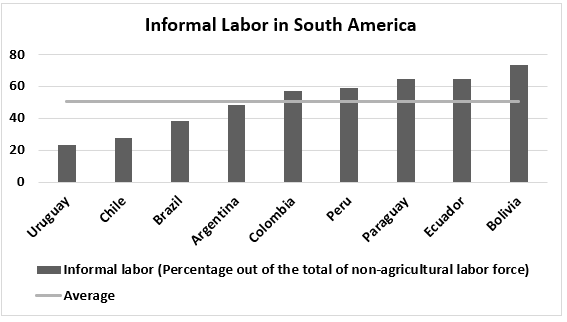

Experts then turn to three other conditions: the high volume of informal labor, more than 70 percent in Peru; high social and economic inequalities; rooted cultural differences and behavioral patterns that include consistent disrespect for laws.

While all these observations are correct, something is still missing. Such conditions must be seen as symptoms of the real problem rather than independent factors that explain apparent inconsistencies. All those conditions are the effects of a single cause: the persistency of state deficiencies, especially in sensitive social issues. And, as has been argued recently, analysts must consider this major condition, along with the trust in the government, while assessing any administration's performance during this pandemic.

The paradox, if any, is that the precarious infrastructural state capacity – especially in issues such as public health and social welfare – before the pandemic explains both the need for radical confinement and social distancing measures and the adverse results after three months of implementation. This problem involves not only the weakness of the state apparatus to provide services and social protections, but also the lack of required social cohesion to contain the pandemic through social distancing. As a result, the government’s efforts have faced severe enforcement and compliance limitations.

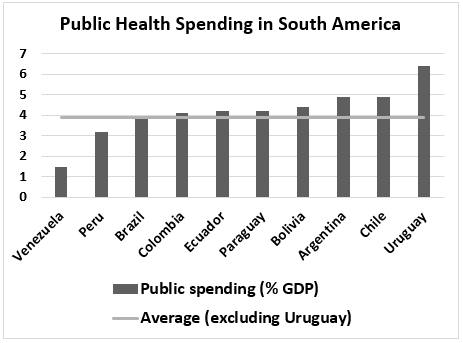

These deficiencies’ origins are rooted on historical processes of state building that cannot be solved easily. However, the persistency and intensity of such failures in crucial areas nowadays – such as social redistribution, public health and education – can be traced back to the last three decades, precisely the decades when economists praised the “Peruvian economic miracle.” After all, those years of austerity especially constrained public spending on these social goods. Despite the presence of economic bonanza, Peru’s public health spending and social programs coverage rank below average in the region.

Furthermore, the economic stability of the “miracle” occurred even as the problems listed by the international press intensified. These situations were not unrelated, but complementary. The lack of regulation on informality worked well as a cushion for the social impacts of the austerity policies. While the state introduced social redistribution programs, those prioritized models focusing on rural population, leaving massive portions of urban residents without benefits and vulnerable. Yet, urban families could still rely on the access to precarious, informal jobs, abundant due to the massive consumption produced by the economic bonanza. This informal employment sector did not vanish, but adapted to the pandemic despite the quarantine.

Confronted by a health and economic crisis, Peru had the resources to invest in improving its precarious health system and introduce relatively high redistributive benefits for those in need during the pandemic. However, the lack of state infrastructure to redistribute those resources in urban areas soon created collateral problems such as the presence of crowds in banks and government offices, aiming to receive benefits or find out if they were eligible for benefits at all. Moreover, the lack of attention to inequality and informality problems reflected on poor urban planning and led to problems of overcrowding and non-compliance that added to pandemic challenges. Today, novice and experienced street vendors flood the streets in major cities.

Clarifying the origins of the paradox is worth noting, since it explains the problems of extreme austerity models for developing countries in the medium and long term. While it is true that responsible monetary and fiscal policies are needed in countries with a history of economic crises, the effects of these measures in the state’s capacity to react to new, pressing challenges such as pandemics or climate crisis must also considered.

Peru is a poster child for the problems of radical austerity. This is not just a technocratic problem of policy design, but a state capacity one. Money means nothing if governments cannot spend it efficiently. Through the last two decades, several attempts to improve the role of the state have been blocked by a right-wing coalition of conservative politicians, neoliberal technocrats, business organizations and mainstream media. As a result, Peru’s impressive economic growth never translated into the infrastructural and social development the country urgently needs.

The government’s response must be assessed given these limitations. Criticism to the specific policies is relevant, but the state’s limitations constrain their efficiency drastically. To be clear, without these measures, the reality would have been worst. Yet, the government and media must undertake the same exercise when assessing the role of individuals. While it is easy to blame the citizenry for complacency and lack of compliance, it must also be acknowledged that such behavior is constrained and shaped by the state’s deficiency to deliver.

Unfortunately, the prospects for progressive changes might be rather pale. First, electoral politics are highly personalistic and non-programmatic, favoring the rise of neophytes and populists that use these issues in campaign but forget them once in power. Without strong parties, electoral accountability becomes a major problem. Second, citizen’s illiberal values were already on the rise due to perceptions on criminality, corruption and immigration. Then, instead of an opportunity to realize and amend previous mistakes, the pandemic could exacerbate the country’s problems in the years to come. The country’s future lacks advantageous political “credit lines.”

Paolo Sosa-Villagarcia is a 2019-20 Fox International Fellow at the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale University and a PhD student with the Department of Political Science at the University of British Columbia.

This article was published June 16, 2020.

.PNG)