Diagnosing at a Distance

Diagnosing at a Distance

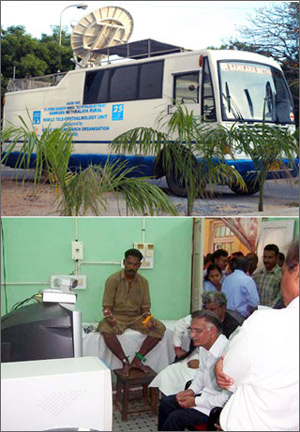

be examined in hospitals hundreds of miles away; below, Indians line up for

telemedicine treatment

KOLAR, India: Visitors thronged a wedding hall in Kolar, a gritty former mining town. No one missed the usual fragrant garlands or glinting gold jewelry. Instead, the guests witnessed a formidable marriage of satellite technology and disease control that could prevent many of India's 40 million diabetics from going blind and make India's medical expertise available to patients overseas.

Trooping upstairs to a bridal dressing room filled with blue-coated technicians, the visitors took turns peering into a retinal camera. An adjacent computer screen instantly displayed each glowing orange orb. This digital image was then sent 280 kilometers away via satellite to Sankara Nethralaya Eye Hospital in Chennai, where Dr. Swakshyar Saumya Pal briskly checked for signs of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy.

Through videoconference, the ophthalmologist told the technicians which diabetics needed follow-up laser treatment. This would be provided free, along with transport expenses and lunch money. The system had to be shut down a few times due to overheating, but most participants expressed satisfaction with the remote care. "People can trust the computer. It's marvelous! The doctor is sitting there and we can get the opinion here," said H.S. Ayub Khan, a teacher who escorted his mother to the mobile clinic.

Telemedicine is gaining momentum in India, amidst public and private efforts to overcome glitches at the grassroots. Faced with the urgent task of spreading big-city medical expertise to smaller towns and rural communities, experts are heartened by the declining costs of connectivity, computer hardware and medical equipment. Such global trends are stirring hope that telemedicine can prove to be an economically viable tool, both domestically and across national boundaries, linking India's leading hospitals with outposts in Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

"In the last one and a half years, the costs have come down by 50 percent," observes Rupesh Agarwal, head of telemedicine at Manipal Hospital in Bangalore, which now connects to nine domestic outposts and will be one of 12 Indian hospitals offering medical advice to health centers in 53 African nations. The pioneering Indian government-sponsored initiative, known as the Pan-African e-network, costs US $135 million and is slated to be fully operational by September 2009 following the recent completion of a satellite hub station in Senegal. Adds Agarwal: "It is an evolving technology. You have to make people aware of it."

In a regional diabetes summit to be held in Chennai in November, the Denmark-based World Diabetes Foundation (WDF) hopes to convince delegates from China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bhutan and elsewhere to adopt telemedicine mobile clinics such as the one in Kolar. Since 2005, WDF has funded screening of more than 18,000 diabetics in southern India.

At the moment, remote care does not come cheap. The white van deployed in Kolar was outfitted at a cost of $250,000, including a satellite dish, generator, computers and high-tech medical equipment. Yet a recent study conducted by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health concluded that this mobile outreach program costs less than half what it would require to screen for diabetic retinopathy at major city hospitals, factoring in the cost of lost wages and travel expenses of patients and their relatives, along with the fixed costs of the hospitals themselves.

Besides, the Indian diabetics who couldn't afford to travel simply wouldn't get screened. Personal treatment is tough in a country with just one ophthalmologist per 107,000 people and the second-largest number of diabetes sufferers worldwide, after China. For other developing countries battling a host of diseases, the urban/rural health divide raises huge concern.

A touch of hubris marks India's urge to use telemedicine to assist Africa, a continent crippled by a medical brain drain. "India has the best doctors anywhere in the world. The experience and clinical confidence of Indian doctors is unparalleled, and this can reach the African people," says Chandil Kumar Gunashekara, medical administrator for telemedicine at Bangalore's Narayana Hrudayalaya Institute of Cardiac Sciences. The hospital, founded by celebrated cardiologist Devi Shetty, was an early adopter of telemedicine and now analyzes an average of 150 electrocardiograms daily for remote patients, including some tribal villagers.

Telemedicine diplomacy forms part of India's broader strategy to draw closer to Africa and bid for a greater share of the continent's energy resources, trade and retail markets. It also supports India's drive to expand medical tourism.

Yet within India, many doctors and other medical personnel outside big cities have been slow to embrace the new technology. Some are reluctant to seek second opinions from specialists. Inadequate bandwidth and power supply are also problematic. Despite such obstacles, however, most local players agree that telemedicine is accelerating. Its pace leaves some overseas analysts impressed.

"Over the last five years, India has moved forward at a staggering rate to implement and use telemedicine. Other countries are still validating the technologies," observes K. Yogesan, president of the Australasian Telehealth Society based in Western Australia.

Certainly, India's head start in space technology provided an advantage over other developing countries in using satellites for telemedicine since 2001. Analysts estimate that several hundred thousand Indians have been assisted via telemedicine since then, although the numbers are difficult to track due to the variety of initiatives. Railway companies, nursing homes and paramedics-turned-entrepreneurs are jumping on the bandwagon. A handful of Indian software firms are specializing in programs related to telemedicine.

"The single most important factor is attitude," argues K. Srikanth, director of product management at the Bangalore-based firm Prognosis Medical Systems. "Most doctors are averse to computers and they don't want to type." Effective telemedicine requires doctors to send digital x-rays and other necessary data, not just exchange views via videoconference, he explains.

In a vote of confidence, India set up a National Task Force on Telemedicine in 2006 and approved a whopping budget of US$100 million. But that money won't be spent prior to a sweeping evaluation report.

The prevailing media stereotype of Third World telemedicine involves a city doctor interacting directly by videoconference with a patient in a remote area. But India's experience suggests that doctor-to-doctor links are more effective.

Accordingly, the Indian Space Research Organisation, known as ISRO, has not concentrated on village-based health centers, where many doctors simply don't show up for work. Instead, the focus is on forging links between major city hospitals and 250 district hospitals in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh states. Such hospitals typically draw 40 to 50 percent of their patients from surrounding villages.

The trick is getting private- sector technicians to install and maintain the equipment in these public hospitals, rather than rely on poorly educated civil servants who are often transferred. In April, for example, Karnataka's health department outsourced this task to a private Bangalore firm. "It should not be under government management," says L.S. Sathyamurthy, ISRO's program coordinator for telemedicine. "Otherwise, it doesn't run."

Telemedicine is proving to be a potent matchmaker. By bringing together private enterprise and government facilities, India stands a better chance of improving its own public health record and sharing its medical brainpower with the world.

Margot Cohen is a journalist based in Bangalore.