A Discussion On Ethical Globalization

A Discussion On Ethical Globalization

Ernesto Zedillo: I would like to start by posing a question to you, which might be a silly question, but still I want to make it, and that refers to the starting point, why speak of ethical globalization? Do you see globalization as a threat or as an opportunity to strengthen, enforce human rights throughout the world?... Do you see globalization as an instrument that could accelerate the establishment of the values and practices of human rights in the world or do you see in globalization something that inherently could weaken the prevalence of human rights in the world?

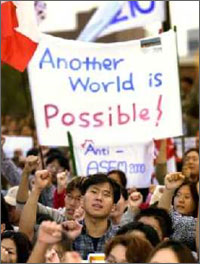

Mary Robinson: Well, I think it's a very good question and I'm happy that you posed it. In a way juxtaposing the words ethical and globalization was intended to be slightly provocative, especially for my friends who are protesting and don't always like to be described as anti-globalization but who are very disillusioned by globalization as it is, and are very amazed that the words ethical and globalization could sit together in an initiative. And what I've been trying to do is to get people to think about globalization... I think it has positive aspects, and it has, at the moment, negative aspects. And in my view it could have many more positive aspects if it were more ethical, and that's to give you a very simple answer. Because I believe that the main driving forces - I identify two in particular - underpinning globalization as we know it today are first of all market forces, increasingly pushing for open markets for trade, the trade in goods, services, and capital. We don't have movement of people, so to a certain extent that's one of the factors, and the other one which worries me a bit and is quite complex is that we're seeing increasingly a privatization of power. We could see that very much in the human rights world where the way in which traditionally there has been accountability has been to pin states as being primarily responsible, but now we're seeing prison services being privatized, education being privatized, health care, and where is the accountability? And I think that this is being accelerated in a way, and there is a belief that if you privatize it will be done better. So for those who are thinking now about public goods, we believe there is a very significant human rights element to that, and we'd like to discuss how we bring it in. So what we're saying is, globalization is a reality, it can be more beneficial, and we look to what the millennium declaration of the heads of states said, that globalization should work for all the world's people. It doesn't do that at the moment, but if it was more values-led, and we don't say that human rights are the only values, we say that they are part of the rules of the road, and there are also the ILO standards, environmental standards, even arms control, whatever, but that there should be more attention paid by governments to these values that they have signed up to. But also there is the role of private sector. How do we have increasing accountability and responsibility of the private sector where what they're doing has such an impact on people? So these are all dimensions linking globalization to the word ethical, as meaning there must be more values impacting on globalization as it affects people in order that it has a more positive effect on the majority who it affects, which it doesn't at the moment.

Jagdish Bhagwati: Obviously any economist whom you mention and ordinary citizens are interested in human welfare. Nobody seriously is interested in globalization or growth or whatever just in itself. There could be political values in growth because you become more powerful and so on, but essentially it's an instrumental variable. So when you talk about privatization for example which has nothing to do with globalization, for you could have the problem in a closed society on an island economy, so the real question is have people overnationalized? Coming from India, to me it's a moral issue to have greater growth because if there is no growth it can be hardly impacted on poverty and when you don't have rapid growth you can't even have social legislation implemented. Like if somebody is beating up on their wife, and your laws against that, unless a wife can walk out and get a job, it's no fat use to have. So to me the economic globalization that brings prosperity goes hand in hand with social legislation, etcetera. So I think we should get away from the focus on human rights or welfare. We really have to ask, is the economic globalization that is going on, is good or bad. On balance, nothing is totally good or totally bad, but it's what the economists call a central tendency. What is the central tendency? My own view is that on balance economic globalization has a human face, meaning you do actually tend to by and large do better. There are downsides, but that's really the issue I think, rather than the conceptualization which you're focusing on, because it's pretty clear, if you have a more free economy, your society is better but you know, where do we go from there? So the real issue I think you people want to focus on is what do you mean by the kinds of human rights and so on, you know that you're interested in terms of defining your social objective, rights objective, and then looking even at globalization in some depth rather than generality. So if we just take one question, like trade and human rights. I'm a trade economist, primarily, so when we talk about human rights, what do we mean by trade? Now to me trade is a moral issue, and I do believe with Ernesto and a lot of other people that the evidence shows that trade leads to more prosperity, and more prosperity leads to more people being put up into gainful employment, so it's not a trickle down strategy but a pull out strategy, and it is really a positive impact on balance. But human rights seem to me to come in on a different dimension, we may be talking poetry pretending it's prose, but for decades we've really written about the need for adjustment assistance. Now if you simply open markets too fast like shock therapy, you could throw a lot of people into dislocation. Now to me that is an important dimension, economists have talked about it. And in fact Western nations do have adjustment assistance programs. When we look at poor countries, the real issue there is that they don't have the money for all to be in any social safety net. So many of the developing countries are getting into trade liberalization because people have demonstrated, like we have, that trade is good for you. It's the transition to more trade and also maintaining free trade that should have a dimension of an adjustment system program. Now I think this is where a commission like yours could try and define what in fact we mean by trade and human rights. We could define human rights as essentially in terms of more concrete dimensions, rather than getting bogged down in conceptualization. I would say rather than the World Bank throwing money at everything that comes its way, it should focus on some important things and one of these could be to develop a program, a systematic program to support economic globalization that's going on trade, both naturally through market forces and through government policies like liberalization, and say look, we're going to finance and systematically support adjustment assistance programs which countries like many poor countries can't afford, so ...it's that level of concretization which I think would be very helpful in your work. I've seen NGO reports which simply say in any time you go into unemployment, that's bad for human rights, well what about the people who are getting employed? What about their human rights? Right? To some extent human rights have become like socialism was when I was younger. I mean any one word, you attach socialism to it, it sounds like a good phrase. I would just urge more concreteness, and try and see exactly, try and relate, be actually focused on the issue, not of what is happening in the context of globalization as you said, but what is happening as a result of globalization, and maybe the real issue is not about cultural globalization which some people worry about but about economic globalization.

Mary Robinson: I don't think there is a fundamental disagreement about the potential benefits and indeed concrete benefits of economic globalization, but what we're saying, taking again the millennium declaration, the benefits are not either benefiting or perceived to be benefiting the majority of people. It's an area where we're trying to link the thinking from a human rights perspective with the work that the World Bank can do.

Arjun Appadurai: I think the issue of the perception of, let's call it the equities involved in globalization is, I think, not an extrinsic issue. It's intimately tied up with the ways in which globalization, in fact even economic globalization, are either driven or not driven... If we consider that human rights is a language we all indeed share, and have our own picture, but overlapping pictures I would say, maybe the right that this initiative could place in the center which no one would deny today ought to be a human right, though it's not the normal folk list of human rights, is the right to participate in the directions that globalization will take. That's a hard right to define, it's not a simple legal right, it's not a simple ethical right, it's not a simple economic right, it's not a simple political right, it's something of all of those, but I would say it's tied up with issue number one. Very large numbers of people need urgently to feel and to be, insofar as things will permit, realistically part of the processes that determine the shape that globalization will take.

Gus Ranis: I welcome the idea of trying to build bridges between the human rights community and the social sciences, including economics which is probably the most difficult one. I also agree with what Jagdish was saying about putting a serious emphasis on particular issues such as adjustment assistance, I think the argument could be made that foreign aid put into a pool of international adjustment assistance would be much more effective way to have foreign aid. The second, I would say would focus more on the human rights situation, not so much on what globalization does for growth or what growth does or does not do for human rights but what it does for the issue of the disenfranchised, including poverty, ethnic divisions within the world, Africa in particular being the focus. I would emphasize two dimensions that I think would be useful. One is emphasizing decentralization, of a vertical type, to global bodies, civil society and so on, and the horizontal type -- the question of moving away from the monopoly of decision making.

Drusilla Brown: You may be very concerned about putting good policies in place that ameliorate the impact of globalization on the poorest. But there's another part of story that what globalization does is either aggravates or it helps political failure. And in the case of child labor globalization has the potential to either improve the quote unquote economy of getting children out of the workplace, but it can actually aggravate it as well ...But you can mess up through globalization and privatization of the security system, turn around and trigger privatization of the education system, and what you do is lose the external effects and social benefits of education that go above and beyond the five things. So when you're thinking through exactly what you think of as human rights and what problems of globalization you're going to solve with a rights approach, you need to think about a lot of these other impacts of globalization that have human rights consequences but don't necessarily have a rights approach solution. ...As you move into globalization and its impact through economic channels, you're going to often find that the problem isn't distribution of market failure, but market failure of the markets functioning, of the political process functioning, which doesn't always have a human rights or a rights based solution.

Philip Alston: I was provoked I suppose by Professor Bhagwati into going back to an ideological analysis of the debate. I think he sought to de-ideologize globalization by suggesting human rights have always been part of development definition, which I strongly contest, and by suggesting that privatization, for example, has nothing to do with globalization. I think it's possible to describe globalization in a very objective technical sort of sense but I think it's also possible to describe it in a highly politicized sense, that it does bring with it, the way it's currently structured, inevitably and in a very big way, deregulation, privatization, the elevation of the power and opportunities of private actors who are not subject to any of the traditional restraints of human rights ...Trade seems to be the engine which will bring whatever consequences we like to see, but my sense is in fact trade brings a limited variety normally of, or limited range of, benefits in terms of economic and political rights. I think when ... talked about the need to look at the voices of the disadvantaged, those who perceive that they are passed by and so on, we can go further than that. It's not just a question of perception, it's a reality that empowerment, that the possibility, not in globalization in the broadest sense but in the actual domestic political processes is being reduced as a result of many of the phenomena of globalization. I think trade is an important part of that. I'm not anti trade in any sense but I think we need to go beyond the trade agenda.

Jagdish Bhagwati: I would simply say whether the language of rights can help you improve and enhance a consciousness in many of these things. I think that's a valid point. That translates partly into this democratic deficit argument, the notion that somehow globalization, through bypassing the masses or something and concentrating benefits is somehow necessarily creating a deprivation of the democratic rights of the poor. That's absurd in my opinion, because on balance it's actually improving their access and their aspirations and so on, and there's a huge literature on that. It's certainly not, they're being deprived of rights anyway, earlier on. The question again goes back to whether globalization is ameliorating, even in a small way, or worsening their situation, and I think that's really what you want to focus on. I really disagree with your conclusion on that, Mr. Alston.

Thomas Hammarberg: There has been quite a bit of discussion in the human rights community about what would be added by a human rights approach to development. Basically there are three things which have been highlighted. One is the one of participation.. With a rights based approach in development work, there will be more focus on participation, that those who are involved, those who are concerned will be more involved. Second, accountability. A key concept in all human rights discourse is accountability. And the third point that has been defined is more emphasis on non-discrimination, that no one should be left out. That of course is combined with the aspect of human rights to focus on the individual. Development tends to focus more on the groups, human rights more on the individual. The other point I wanted to mention is that the human rights standards are international. We talk about them as universal. For me I was representing the UN in Cambodia for a couple of years, there was one very clear illustration of the importance of the international human rights standards. It was a period when textile was developing around Phnom Penh, so many companies came from outside to set up their factories, and the working conditions were terrible, awful. When human rights people came in we discussed with the employees to improve conditions of salaries, working conditions of work hours, and all those aspects. The problem was that when we put our requests too toughly the risk was that they would leave and move to another country. And even the workers themselves were afraid of the human rights discussion, because they preferred a very low salary to unemployment. That to me illustrates that we have international standards which would create the situation where countries would not compete with bad working conditions in order to attract investors from outside.

Ayesha Imam: ...It's not so much that globalization causes poverty...but globalization is part of a long historical process...and the issue much more is what is this phase of globalization doing, which terms are particular actors, are we talking about nation states, or are we talking about particular sectors, indigenous groups participating, because there are issues that we need to focus much more on the possibility to participate in the process and directions, because otherwise the benefits came to be by chance. When you talk about vulnerable sectors, even nation states, depending on where they are in the world...so the benefits are then happenstance rather than possibilities of being able to arrange things that don't only benefit those who have power currently.

Ben Kiernan: There needs to be a move away from two current positions taken by human rights groups. One is the sort of the purity of the gadfly, that there are a good deal of human rights stands which have to be constantly kept in the public eye, which sometimes are the enemy of significant improvement if they're the only position being put forward. The other is a kind of standoff situation which is that the human rights group has one position and the government or international corporation or business has another and they just agree to disagree and argue opposite on different things on the same issue. There's also a standoff between the present and the past. Human rights groups sometimes say that this is the way legal rights and human rights have got to be implemented. And others who are actually so value their countries say 'What about the heritage we're facing?' and so on. That came up with the United Nations approach in Cambodia...There's the current standoff between the UN and the Cambodian government, between different western groups who want the tribunal to go forward or not go forward on the basis of some saying that the tribunal should go forward, the UN shouldn't be involved in order to strengthen Cambodian human rights and the legal system, and others will say, well, no, that will legitimize its defects. Well, both will have to happen. It's impossible to stand aside and say it's time for this or that. You can't really strengthen the system without also legitimizing its defects, you can minimize that, it's not impossible, but it's not a choice to stand up and do nothing or just criticize with the purity of the gadfly.

Michael Merson: A lot of us have tried to use the human rights approach as an advocacy tool more than anything else, more than a legal tool, I'm not sure we've been successful and I often feel we put people's back up in the health sector when we use terms like human rights. So one of the things I would just put forward with my own course is to encourage an objective look at all this and what we've learned. We're still in the midst of terrible HIV/AIDS epidemic, and if we can write things in this area we should and probably can gain a great deal. We're gonna face in the next five years some incredibly difficult questions. Either 30 million people are gonna die or 100 million people are gonna die in the next ten years, and it's gonna come down to whether there's access to these drugs. The human rights approach can work and can change the attitude of the private sector, change the attitude of governments, it would be wonderful. Maybe this belongs more to your Africa initiative, I don't know ...but it's a hot issue and one that your new initiative, if it took it on, could make some very important observations.

Harold Hongju Koh: I think that there are three things that are emerging that are relevant to the mandate of this new initiative. The first is Ernesto's question: what is added to talk about globalization through an ethical lens. I think the comments we've heard are basically three, that you could think of it as either obscuring or vague or superfluous because something else real is going on, and this is just more of a cover. A second view is that it's not superfluous but it's in some ways peripheral, but the third possibility is that it's actually counterproductive to think about things in rights terminology, that it misshaped the priorities. I've heard the first two more than the third, although there are people out there who certainly believe the third. The second thing is, what is your response to this? You know, what's the value of speaking about this in a rights rubric, and I think that's what Thomas Hammerberg was really addressing. It focuses on the value of participation, accountability, standards, priority setting, etc, but I think what Arjun Appadurai did very helpfully is to say that you're really trying to define who is the constituency and the group being represented by the Ethical Globalization Initiative. The traditional human rights movement represents the various individual kinds of rights or collections of rights, your political and civil rights, indigenous rights or whatever. But what he's saying is you're representing a broader right, namely the right to participate in globalization in which there are multiple addressees, some of whom are governments, some of whom are corporations, some of whom are intergovernmental organizations. The third method's just an obvious point, but I think you could say it more directly than you have up to this point, that this is really about economic, social, and cultural rights in the next phase of the human rights movement. Nobody is really saying you shouldn't talk about civil and political rights in a rights-based approach. Kim Jong Il even says that he provides civil and political rights, he just provides them in his own way. But I think in this area what's being fundamentally contested is whether globalization providing certain things has to do so as a matter of right or as a matter of resource allocation or other kinds of concerns. Even some of the strongest advocates of a political and civil rights based approach don't favor this approach, and I think by putting globalization in these terms, you're explicitly saying, we've come to the age of rights in which economic, social, and cultural rights is the core and the core constituency is those disenfranchised from the process of globalization, and they need to have a right to resources and a right to participate as a way of expressing that right to resources.

Comments

Your Ethical Globalization Initiative website link sends users to an escort page. Editor's Note: The original link has since been discontinued. The problem link was rermoved, and we thank you for taking the time to write.