Do the Awakening Giants Have Feet of Clay? – Part I

Do the Awakening Giants Have Feet of Clay? – Part I

BERKELEY: Over the past few years the media have been all agog over the rise of China and India in the international economy – and their remarkable recovery in this current global recession. After decades of relative stagnation, these two countries, containing nearly two-fifths of the world population, have had incomes grow at remarkably high rates since 1985.

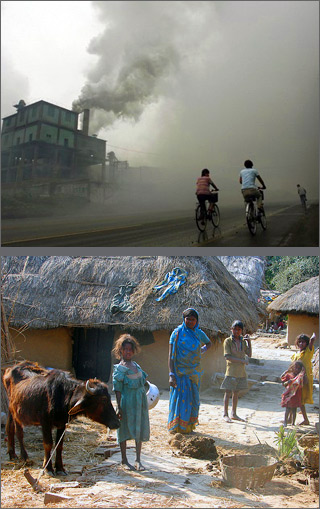

In the world trade of manufacturing, China, and in that of services, India, have made big strides, much to the consternation – as yet largely unfounded – of workers and professionals in rich countries. The industrial growth along with acquisition of international companies by China and India attract much of the Western media attention.

But more revealing is what has happened to the lives of people inside these two countries and under what structural constraints. It’s imperative to demolish myths that have accumulated in the media and parts of academia around the economic achievements of China and India and get a better sense of the real challenges faced by them.

In the recent, often breathless, accounts of the economic rise of China and India, a set of simple generalizations have become part of the conventional wisdom. The familiar story runs along these lines:

There are, of course, some elements of truth in this story, but through constant repetition it has acquired a certain authoritativeness that, as closer scrutiny shows, it does not deserve. The story is far too oversimplified.

First, two relatively small points about industrial growth in China: While China is possibly the largest single manufacturing production center in the world for many goods in terms of volume, it is not so in terms of value-added; the world share of US or EU in this area is still substantially larger.

Similarly, although the industrial growth rate has been phenomenal in China, South Korea and Taiwan grew at a faster pace in value-added terms during the first 25 years of their growth spurt. More important, contrary to popular impression, China’s growth over the last three decades has not been primarily export-driven. While China had major strides in foreign trade and investment during the last 15 years, before – during the period between 1978 and 1993 – the nation had a high average annual growth rate of about 9 percent.

Much of the high growth in the 1980s and the associated dramatic decline in poverty happened largely because of internal factors, not globalization. These internal factors include an institutional change in the organization of agriculture, the sector where poverty was largely concentrated, and an egalitarian distribution of land-cultivation rights.

While expansion of exports of labor-intensive manufactures did lift many people out of poverty in China, the same is not true for India, where exports are still mainly skill- and capital-intensive. It is also not completely clear that economic reform is mainly responsible for the recent high growth rate in India. Reform clearly made the Indian corporate sector more vibrant and competitive, but most of the Indian economy is not in the corporate sector, with 94 percent of the labor force working outside this sector, public or private. Consider the fast-growing service sector, where India’s information-technology-enabled services have made a reputation the world over. But that sector employs less than half of 1 percent of the total Indian labor force.

While globalization generates some destabilizing forces, the rise of inequality is not the highest in the globally more exposed coastal regions of China, but rather in less-integrated interior areas. Contrary to popular impression, the level of economic inequality is actually lower in globally more integrated China than in India. In particular, domestic factors like the much higher inequality in land distribution and education drive greater inequality in India.

For the financial press, China and India have become poster children for market reform and globalization, even though in matters of economic policy toward privatization, property rights, deregulation and lingering bureaucratic rigidities both countries have demonstrably departed from the economic orthodoxy in many ways. If one looks at the figures of the widely-cited Index of Economic Freedom of the Heritage Foundation, the ranks of China and India remain low: out of a total of 157 countries in 2008, China’s ranks 126th and India 115th. Both are relegated to the group described as “mostly unfree.”

Although there is no doubt that the period of socialist control and regulations in both countries inhibited initiative and enterprise, it would be a travesty to deny the positive legacy of that period. It is arguable, for example, that the earlier socialist period in China provided a strong launching pad particularly in terms of a solid base of education and basic health, rural infrastructure, a rural safety net from equitable distribution of land cultivation rights, regional economic decentralization and high female labor participation.

A major part of the legacy of the earlier period in both countries is the cumulative effect of the active role of the state in technological development.

The relationship between democracy and development is quite complex, and authoritarianism is neither necessary nor sufficient for development. In fact, authoritarianism has distorted Chinese development, particularly as powerful political families distort the allocation of state finance and unaccountable local officials in cahoots with local business carry out capitalist excesses, both in land acquisition and toxic pollution.

Democratic governance in India, on the other hand, has been marred by severe accountability failures. Nor can one depend on the prospering middle classes to be sure-footed harbingers of democracy in China. In many cases the Chinese political leadership has succeeded in co-opting the middle classes, including the intelligentsia, professionals and private entrepreneurs, in its firm control of the monopoly of power, legitimized by economic prosperity and nationalist glory. Indian democracy derives its main life force from the energetic participation of the poor masses more than that of the middle classes.

While both China and India have done much better in the last quarter century than they have during the last 200 years in the matter of economic growth, one should not underestimate their structural weaknesses. Many social and political uncertainties cloud the horizons of these two countries for the foreseeable future.