Dubai’s Kerala Connection

Dubai’s Kerala Connection

DUBAI: By all accounts Dubai, the most flamboyant of the seven states that make up the United Arab Emirates, has reinvented itself as one of the most globalized corners of the world, where education, a favorable business climate, and internet access count for more than geography. But unlike other success stories for enthusiasts of globalization, the important players giving Dubai an extreme makeover are largely hidden from public view in a land whose wealth now comes more from business and tourism than oil and natural gas. They are the invisible foot soldiers of globalization.

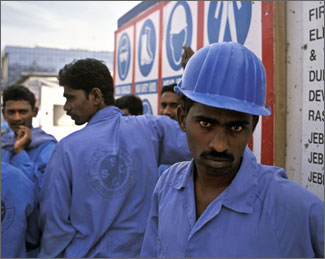

Largely hidden behind the glitz of the shopping malls and fancy resorts are hundreds of thousands of unskilled South Asian workers who toil in the hope their labor will benefit home and family. Thanks to four decades of their sacrifices, the effects of globalization have been trickling down to places like Kerala, a tiny Indian state on the Arabian Sea, where remittances from workers in the Middle East account for more than 20 percent of the state's income.

But the price has been high.

Blue-collar Indian workers in the UAE, including Dubai, amount to an exploited underclass with no rights, no unions, and no stake in country's burgeoning wealth, say human rights groups. In neighboring Saudi Arabia, a recent Human Rights Watch report says many of the country's more than one million Indian migrants live in "conditions resembling slavery." The document highlights the widespread practice of forced, around-the-clock confinement of Indian maids, often in unsafe conditions. And a US State Department report on worldwide human trafficking faults the UAE and other Gulf states for commonplace labor abuses like withholding pay and passports.

Employers usually confiscate passports and residence permits when workers arrive at Dubai International Airport, making it virtually impossible for laborers to seek better jobs or quit and go home. Migrants typically cannot obtain exit visas without the approval of their sponsor or employer. The story of these faceless men and women, who live in labor camps and seedy apartments, is gaining attention in the usually self-censored UAE press, which now regularly reports on worker protests over delayed pay and substandard living conditions.

"I've been in Dubai eight years," says taxi driver Rajab Khan from Pakistan's Punjab Province. "But I don't make enough money to have my family join me. We in the laboring class must live apart." He shares a grim one-bedroom apartment with 10 other Pakistanis and Indians. Khan returns to Pakistan once a year to a new home he built for his family, though he worries how long work in Dubai will last.

Since the flush 1970s, when global energy prices began to soar, the earnings of these foot soldiers of globalization have financed much of India's trade deficit, according to a recent study by the British Department of International Development and the University of Dhaka in Bangladesh. And Indians working in the Middle East – mostly in the UAE and Saudi Arabia – amount to only one percent of the country's total labor force. Their remittances have considerably impacted the regional economies of poorer Indian states like Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh in addition to Kerala.

The some 3.1 million Indians in working in the Persian Gulf send home about US$7 billion a year, according to the most recent figures available, a 2003 report by the Indian Bureau of Foreign Employment. Neighboring Bangladesh has about 1.8 million workers in the Gulf who send home US$2.9 billion annually, followed by Pakistan with a million workers who remit US$1.3 billion. Figures for Sri Lanka are less precise, but in 2001, the nearly one million Sri Lankans in the Gulf sent home about US$700 million.

Overall, the Reserve Bank of India says Indians of the worldwide diaspora remit about US$15 billion a year – slightly over three percent of the country's gross national product. So far this year, India's economy has grown at a greater-than-expected seven percent, thanks to strong consumer spending – spending that is bolstered by expatriate Indians, including those in the UAE.

In Kerala, the exodus of workers to the Gulf also has resulted in smaller families and more families headed by women, giving these de facto heads-of-household newfound authority. Once more, population growth has been reduced by 20 percent since studies began in 1981. Gulf remittances also have contributed to a hefty six percent decline for Muslims living below the poverty line and a three percent decline for Hindus, according to a 2002 study by the Center for Development Studies in the state capital, Thiruvananthapuram.

Indian workers at a high-rise construction site in Dubai say the money they send home pays for new houses, better schools, uniforms, and textbooks for their children, and dowries for marriage-age daughters. Others tell of having to repay sizable loans, some at nearly 100 percent interest, to secure jobs and visas for the UAE. Meanwhile, the poorest Indian villages are getting new mosques and temples, satellite dishes, and outdoor advertising for all manner of consumer goods, especially flush toilets, thanks to their remittances.

The UAE's substantial investment in fiber optics allows remittances to move from the rich to the less developed world at the speed of light, though the old practice of carrying gold jewelry or ingots back to India hasn't disappeared – to the chagrin of UAE and Indian government economists. In Dubai, where there are no personal income taxes, banks compete to send remittances anywhere in India inside 24 hours. As the evening Muslim call to prayer echoes from a multitude of minarets, construction workers in greasy coveralls line up at banks in the city's old souk, cashing monthly paychecks of about US$200 – the cost of a mid-range Dubai hotel for the night – and sending home as much as half of their earnings.

But unskilled workers worry about their ability to keep the remittances coming home. "There are too many South Asians here now, and many are going home, not to return," says Khan, the taxi driver. "You have to work 365 days a year, no days off."

Khan may be right. While South Asian professionals are still welcome, the UAE has slowed down accepting visa applications from Indians for unskilled jobs, turning instead to less troublesome Filipinos, Indonesians, and even Romanians. "I recently put an advertisement in the local newspaper for 50 jobs and 700 Indians showed up," recalls P.K. Girish, general manager of one of Dubai's 400-plus hotels and an Indian by birth. "There's no doubt Dubai needs to fine tune its labor market." Thousands of illegal South Asian immigrants are said to live in slums in the neighboring Emirate of Sharjah, he says. Throughout the Gulf, indigenous Arabs are being hired for managerial jobs once reserved for Indians in what amounts to an affirmative action policy to fight local unemployment.

Indians of every social class gripe about discrimination and the lack of rights, like citizenship for Indian children born in the UAE. Still, few seem anxious to return to India. "Life is so harsh in India," say Trevor Rose, a native of India who earned a Canadian passport only to return to Dubai. "This is still better."

Steve Raymer is an associate professor of journalism at Indiana University in Bloomington and was a National Geographic Magazine staff photographer for more than 20 years. He is working on a photographic book about the Indian Diaspora.