East Asia’s Free for All

East Asia’s Free for All

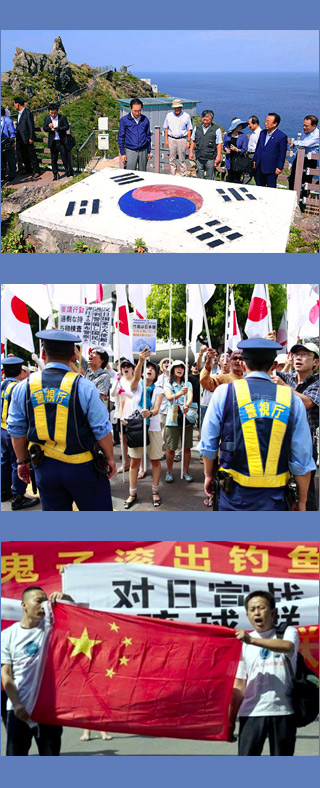

HONG KONG: With the Japanese flag ripped from the ambassador’s car in Beijing, the dispute over ownership of tiny islands in the East China Sea has reached new heights. It’s not only China. Japan’s reignited dispute with South Korea nearly seven decades after the end of World War II suggests that Japan still has not regained the trust of countries that it once invaded and occupied. The disputes also are a reflection of the decline of Japan, the emergence of new power centers and rising nationalism.

The roots of these territorial disputes go back to the 19th century, when Japan defeated China in the 1894-1895 war, fought over Korea. In the subsequent treaty, China was forced to end its suzerainty over Korea. Japan refused to recognize Korea’s independence, occupying it in 1905 and annexing it in 1910.

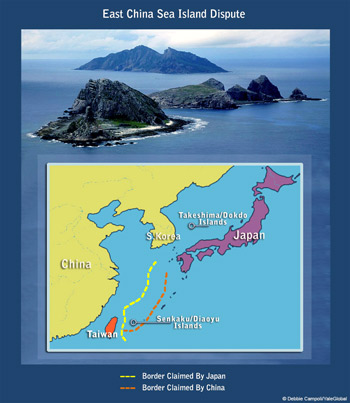

In early 1895, the Japanese cabinet incorporated the Senkakus – five uninhabited islets and three rocks with a total area of 7 square kilometers, known as the Diaoyu islands to the Chinese – into the country’s territory. While tiny, they’re much bigger than the islands in dispute between Japan and South Korea, called Takeshima by the former and Dokdo by the latter.

Japan is in control of the Senkaku islands while the Koreans administer the Dokdos.

As the old saying goes, possession is nine-tenths of the law. Japan does not recognize China’s claim, insisting there’s no dispute over the Senkakus. A similar position is taken by Korea on the Dokdos.

The disputes take up a disproportionate share of attention for a country struggling with the aftermath of an earthquake and nuclear disaster, demographic challenges and economic stagnation.

Japan has seen revolving door governments for the last six years. Lee Myung Bak, president of South Korea since 2008, has dealt with five Japanese leaders. Hu Jintao, China’s president since 2003, has dealt with seven. Such a quick succession means that no leader is in office long enough to get a grip on foreign policy. So Japan, despite an attempt in 2009 to integrate itself more into Asia, is as reliant as ever on the United States.

Inevitably, the United States is enmeshed in Japan’s problems. A Japanese official, Shinsuke Sugiyama, sought and obtained confirmation in Washington August 22 that the Senkaku islands are covered by the US-Japan security treaty. That’s to say, the United States will help defend these islets if attacked by China. China strongly opposes any application of the US-Japan security treaty to the Diaoyu islands.

The United States does not want to be dragged into a war with China over a bunch of rocks but, at the same time, it needs to be seen as a reliable ally not only by Japan but also by South Korea, the Philippines and others. While on the surface the disputes are over insignificant bits of rock, their real value lies below the seabed, believed to hold large deposits of oil and natural gas.

In fact, Japan and the United States are currently holding a month-long military drill that reportedly involves taking back islands seized by enemy troops. They insist that the exercise is not aimed at any country.

In the dispute between Japan and South Korea, Washington is caught in the middle as its two most important allies in Asia are at each other’s throats. The United States, bound by treaty to defend both Japan and South Korea, has been trying to convince Tokyo and Seoul to work more closely together on security matters, but in June, South Korea abruptly backed out of a pact to share military information with Japan. That same month, the three nations did hold joint military exercises.

Aggravating the two sets of territorial disputes is rising nationalism in all three countries, though the recent flare-ups had different triggers.

On August 15, a boat carrying Hong Kong political activists circumvented Japanese coast guard vessels. Seven people landed on the main Diaoyu island, waving both Chinese and Taiwanese flags. Taiwan, formally known as the Republic of China, also claims the islands.

The activists, evidently wanting to spur Beijing and Taipei into more aggressive action to assert territorial claims, refused to leave the island. The Japanese coast guard detained them, triggering a diplomatic protest by China.

The highly publicized detention and subsequent deportation stirred emotions in China. Despite China’s policy of avoiding confrontations with Japan, by August 19 anti-Japan protests were held in cities across China, Beijing is not averse to showing Japan how much pressure it’s under.

While activists on the ground spurred the dispute with China, albeit with tacit support, South Korea’s was a top-down exercise, with President Lee Myung-bak’s decision to visit the Dokdo islands on August 10 – a first for a Korean leader. Lee’s term ends in February, and his successor will be chosen in December elections.

Five days later, Seoul marked Liberation Day, which coincides with Japan’s surrender in the Second World War.

In his Liberation Day speech, Lee demanded that Japan take “responsible measures” for having made sex slaves of Korean women during the war to serve its soldiers. The previous day, he called on Emperor Akihito to apologize to the victims of Japanese colonialism before visiting Korea. Japanese officials report the emperor had not indicated an intention to visit South Korea.

Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda then wrote a letter to Lee protesting the island visit to Takeshima and asking the Korean leader to apologize for demanding an apology from the emperor. In what may well be an unprecedented move, underlining the emotions and political posturing of these disputes, the South Korean government refused to accept Noda’s letter, announcing that it would be returned. When a Korean diplomat arrived to return the letter, the Japanese foreign ministry refused to admit him. The letter was eventually returned by registered mail.

Japan’s relationships with its neighbors have an ongoing theme: Despite many official government apologies for past behavior, politicians whose actions raise questions as to whether Japan is actually contrite continue to emerge.

On the anniversary of the Japanese surrender, August 15, two members of Noda’s cabinet visited the Yasukuni Shrine, where 2.5 million of Japan’s war dead, including Class A war criminals, are enshrined – despite a pledge by Noda that no member of his cabinet would visit the site. The Noda administration labeled them as “private visits.”

On the issue of wartime sex slaves, Japan acknowledged responsibility and apologized in 1993. Still, some politicians continue to question whether the events occurred. Toru Hashimoto, mayor of Osaka, a strong contender to be the next prime minister, has asked Korea for proof.

Earlier this month, Noda agreed to dissolve the lower house and hold an election “before long” in return for support for a tax measure. Japan could have another prime minister in a few months.

In the meantime, the government is trying to organize and improve relations with neighbors. Japan has announced that it will replace its ambassadors to China, South Korea and the United States in an attempt to have firmer control over its foreign policy.

A coherent, longer-lasting government for Japan is essential for settlement of the scramble for natural resources and rising nationalism in China and South Korea. Attempts to use these territorial disputes for political ends do not bode well for regional peace and stability.

Frank Ching is a Hong Kong–based journalist and writer whose book, “Ancestors: 900 Years in the Life of a Chinese Family,” was recently republished in paperback. He can be reached at Frank.Ching@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter: @FrankChing1