East Asia’s Troubled Waters – Part III

East Asia’s Troubled Waters – Part III

FUKUOKA: One year after massive street protests revealed the depth of anti-Japanese sentiment among the Chinese public, two court rulings have further soured Tokyo-Beijing ties. District courts in Nagano and Fukuoka in March affirmed the historical record of forced labor in Japan during World War II, but rejected compensation claims by Chinese victims because the statute of limitations had expired.

The latest impasse highlights the mismatch between Japan’s approach to coming to terms with its wartime past and aspirations for a leading role on the world stage – and could threaten the ability of major Japanese firms to do business in China. Although Japan has so far managed to resist the global trend of redressing historical injustices, greater pressure produces new incentives for Japanese government and industry leaders to address the tsunami of reparations demands from forced-labor survivors.

Former laborers will soon file class-action lawsuits against Japanese corporations in Chinese courts, marking the first litigation in China stemming from Japan’s war conduct. The Beijing government permits the lawsuits because 14 forced-labor cases filed in Japanese courts over the past decade have failed to produce apologies or monetary damages.

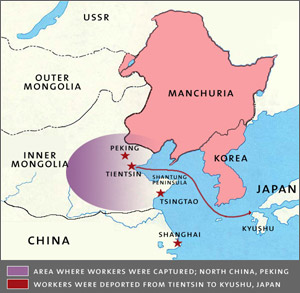

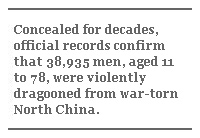

Yet even Japanese judges regularly find that the state and private companies jointly engaged in illegal conduct by forcibly bringing the Chinese plaintiffs to Japan and forcing them into brutal labor at mines, docks and construction sites between 1943 and 1945. Concealed for decades despite direct questioning in Japan’s parliament, official records confirm in meticulous detail that 38,935 men between the ages of 11 and 78 were violently dragooned from war-torn North China.

The overall death rate was 17.5 percent, but at some of the 135 corporate worksites fully half of all laborers perished. Most of the firms involved are still in business, including Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Kajima, Sumitomo and Nippon Steel.

In 1946, remarkably, Japanese companies became “double winners” by receiving generous payments from state coffers as indemnification for costs incurred through their use of Chinese workers. In 1950, the government quietly set up a “special deposit system” for wages that corporations never paid to the Chinese and hundreds of thousands of Koreans conscripted during the war for work in Japan. Tokyo reluctantly admits that the Bank of Japan holds millions of dollars in unpaid wages, unadjusted for six decades of inflation and interest.

Wartime cabinet minister Kishi Nobusuke served as the bureaucratic czar of forced labor, before spending three years in prison as a Class A war crimes suspect during the Allied Occupation. Kishi went on to become Japan’s prime minister from 1957 to 1960 and is the founding father of the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party. Kishi’s grandson, Abe Shinzo, serves as chief cabinet secretary and is frontrunner to become prime minister later this year.

Foreign Ministry records declassified in 2002 revealed that the Kishi administration deliberately suppressed the truth about Chinese forced labor to block grassroots efforts by Japanese activists demanding accountability and evade state reparations claims from China. In 2003, the Foreign Ministry searched a basement storeroom and found 20,000 pages of Chinese forced-labor records submitted by corporations 57 years earlier, underscoring the state’s track record of insincerity.

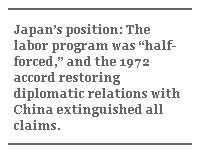

The Japanese government’s current position is that the Chinese labor program was “half-forced” and the 1972 accord that restored diplomatic relations with China extinguished all compensation claims. Beijing, having come to dispute that interpretation partly in reaction to rising Japanese nationalism, holds that individual claims by Chinese citizens remain open.

The March 29 decision by the Fukuoka District Court was closely watched, in China and elsewhere, because Mitsubishi Materials Corp. mounted a brazen defense based on revisionist historical arguments. Corporate lawyers denied forced labor or mistreatment of any kind in its local coal mines, despite fatality rates of 25 percent.

Mitsubishi also heaped criticism on the American-led Tokyo war crimes trials of 1946 to 1948, openly questioning whether Japan ever “invaded” China at all. The company warned that a redress award for the elderly Chinese plaintiffs, or even a court finding that forced labor had occurred, would saddle Japan with a “mistaken burden of the soul” for hundreds of years. Due to a deadline for filing claims, Mitsubishi was not penalized.

In unusual remarks at the Nagano District Court, the judge expressed his personal desire that Chinese forced-labor victims be compensated through non-judicial means. Germany, the leading model for proactively rectifying past injustices via reparations, provides the obvious example for settling WWII forced-labor accounts.

The “Remembrance, Responsibility and the Future” Foundation was established in 2000, with $6 billion provided by the German government and more than 6,500 industrial enterprises. By late 2005, about 1.6 million forced-labor victims or their heirs had received individual apologies and symbolic compensation of up to $10,000. Similarly, the Austrian Reconciliation Fund recently finished paying out nearly $350 million to 132,000 workers forced to toil for the Nazi war machine, or families.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, Swiss and French banks and insurance companies paid hefty restitution for assets looted from Holocaust victims. In 1988, both the US Congress and the Canadian Parliament granted official apologies and individual compensation to ethnic Japanese interned during the war. The ongoing reparations movement includes historical truth commissions in dozens of countries, the return of ancestoral lands and human remains to native peoples, and the rewriting of educational curricula to honestly confront past wrongdoing.

Japan, by contrast, has largely gotten away with its anachronistic approach. With strong backing from the US State Department, Japan’s government and corporations have refused to compensate – or even clearly apologize to – tens of thousands of former Allied POWs who performed forced labor. Some 10,000 Koreans and 300 Allied POWs provided forced labor for Aso Mining Co., the former family business of Aso Taro, Japan's current foreign minister.

South Korea’s Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under Japanese Imperialism works to repatriate the remains of Korean conscripts that have languished in communal mausoleums in Japan for over half a century. The Seoul government plans to compensate surviving laborers itself, having waived its right to claim their unpaid wages in 1965 in exchange for badly needed economic assistance from Japan.

But new forced-labor lawsuits in Chinese courts might push Japanese leaders into enacting a German-style compensation fund based on self-interest. A shifting calculus of costs and benefits related to economics, security and international reputation could make reparations less painful than perpetual intransigence.

Losing Chinese market share in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics in 2008, from government action or consumer boycotts, would seriously hurt Japanese corporate balance sheets. A concrete step toward historical reconciliation would decrease military tensions and improve Japan’s image throughout the region. And unless China drops its objections, Tokyo’s desire for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council will remain blocked.

The center of gravity for the forced-labor redress campaign is steadily shifting to China. Chinese individuals and corporations contribute hundreds of thousands of dollars to a fund to support China-side litigation efforts. Petitions demanding compensation are presented to the Chinese offices of Japanese conglomerates amid heavy media coverage. A five-volume collection of oral histories of forced laborers was recently published, as the feisty internet generation picks up the reparations torch.

Increased global activism and media attention expose the incongruity of Japan’s pretensions to leadership and its failure to address past transgressions. Until Japan moves beyond narrow legalism and conforms to emerging standards of moral accountability, the nation will have few followers.

William Underwood, a faculty member at Kurume Kogyo University, is completing a doctoral dissertation at Kyushu University on the topic of Chinese forced-labor redress. He can be reached at kyushubill@yahoo.com.