Economic Impacts of COVID-19

Economic Impacts of COVID-19

CONCORD: If the stock markets around the world are telling us anything, it is that there is more uncertainty and pessimism about the economy than there were some weeks ago. This is a reasonable reaction, given that the virus is still spreading, its severity and probable duration are increasing, and there are both supply and demand shocks to a world economy that is much more interlocked than many realized. Even if heroic and costly efforts to “flatten the curve” succeed, there is a chance of rebound cycles that cause either renewed isolation with its economic impacts or higher mortality. The global economy confronts a range of scenarios.

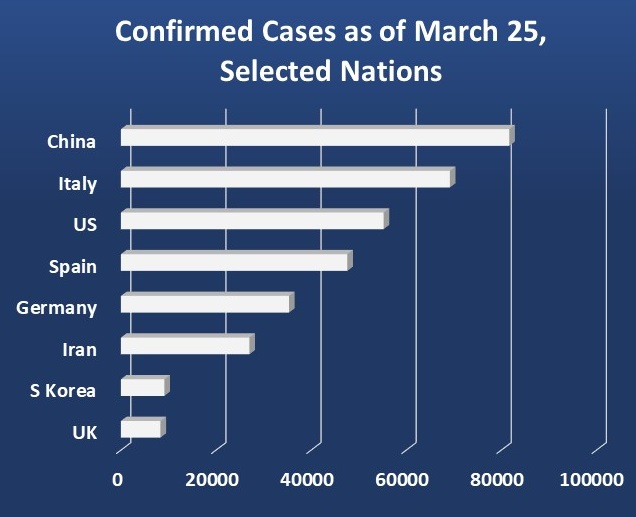

First, this appears to be a hard virus to confine. People showing no symptoms shed the virus, so without frequent and widespread testing, billions of people must self-isolate for long periods. Even China or South Korea, who have done well in the first round, may find themselves dealing with periodic outbreaks. Singapore and Taiwan already report second waves of outbreaks. A fast, affordable and reliable test would be immensely helpful and may eventually be developed. The US president wavers between following public health experts, who advise confinement of large numbers for long periods while hospitals are under stress, and allowing normal activities in a few weeks.

Second, the likely availability of a vaccine next year should limit the time of large economic impact. It is even likely that a number of medicines will manage mild and moderate, if not severe, cases and limit the extreme stress on medical personnel and hospitals. This may allow many workers and students to return to somewhat “normal” conditions, while older people or those with conditions that raise their risk must be careful but not completely isolated. Caution is required as COVID-19 presents many unknowns. US data suggest patients aged 20 to 54 represent about 40 percent of hospitalizations, and any return to routines assumes the virus does not mutate to become more deadly. An affordable, rapid antibody test may allow identification of those with immunity, allowing them to avoid isolation.

Third, managing the economic impact of the virus will have consequences. The crisis has renewed movements toward negative interest rates on government debt. There are massive increases in central bank bond holdings. Huge fiscal deficits will add substantially to total government debt. Trade patterns will be adjusted, some permanently, as many nations move toward producing more goods themselves. Companies will add resilience to price and speed as goals. Companies may back off from just-in-time inventory management and stringent controls; multiple sourcing, stockpiling and local production will become standard practices.

Finally, nations must consider the notions of moral hazard and the safety net in scrambling to respond, setting priorities on industries to be saved, whether major multinationals like Boeing or small businesses like restaurants.

The consequences of prolonged zero or negative interest rates on banks, insurance, pensions and savings for retirement or college will be substantial, even assuming no inflationary impact. Some argue that wealth concentration has led to chronic demand shortfalls while others argue that some combination of capital saving technology – such as fewer hotels when there is Airbnb and underinvesting monopoly firms –have driven low investment rates even with favorable tax treatment. This could explain the explosion of stock buybacks.

Consider many large companies that have routinely issued debt and used profits not to invest, build up liquidity and capital or do R&D, but instead bought back their stock to keep prices high. Critics question whether these companies should receive low-interest loans or grants – or whether the government should offer to buy their “treasury stock,” the repurchased shares, at a price reflecting the risks incurred. Such government purchases would dilute ownership of existing shareholders, allowing the shares to eventually be sold on public markets.

Company lobbyists and apologists argue that this shock was unforeseeable and they should not be punished. But having little cushion assumes that nothing bad will happen and, when it does, others will help out. Perhaps the low-interest loans could go to those that had limited stock buybacks and kept a reasonable ratio of equity to debt as well as those that retain or quickly rehire employees. The offer to buy corporate treasury stock would be for those who used profits and debt to push up their stock price. Private equity that buys companies, charges fees, adds to debt and then goes bankrupt will not suffer much, but this experience might educate lenders about debt covenants. It must be said that long periods of low interest rates have pushed lenders to be lenient.

Meanwhile, more and more jobs are gig jobs – people who are independent contractors with little or no job security. As many as a third of US jobs depend on that gig economy and the numbers are higher in emerging economies. Gig workers and “regular” service employees are often small businesses or work for such small businesses that operate on slim margins. Many are likely to go under without loan forbearance or special breaks, including subsidies, and many will lose their livelihoods for no fault of their own. Solutions might focus on providing a basic income for workers along the lines of Andrew Yang’s universal income plan or more generous and flexible unemployment insurance that would supplement incomes dropping below normal levels for a period of time, yet unknown.

The crisis underscores how strong public health systems and policies protect all. The United States is the only one of 22 developed countries failing to guarantee paid sick leave. Health insurance based on a share of income, as the US Affordable Care Act did with subsidies, would help eliminate the current US link in which a good job is needed to afford insurance unless the employer subsidizes health care. A shameful exemption of paid sick leave for large employers in the second US coronavirus relief bill must be reconsidered. In a pandemic, it makes no sense to force people to choose between infecting others or feeding their family.

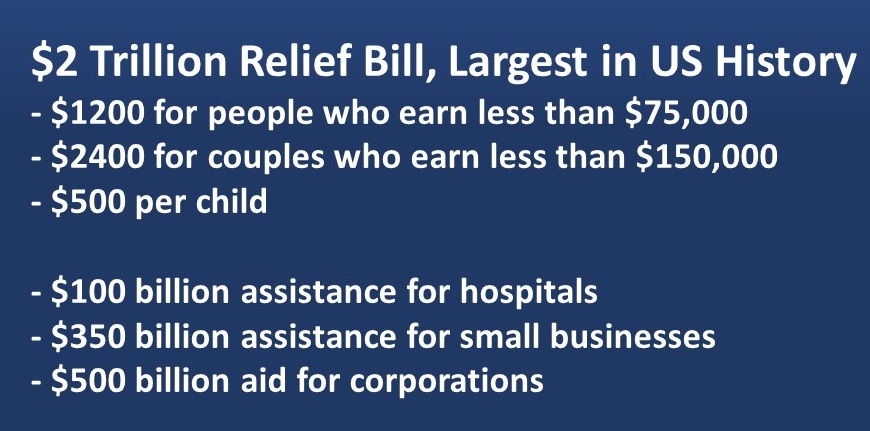

All of this costs money. If some changes become permanent, these cannot be financed simply by borrowing or printing money over a long period. An international accord to chase down tax havens and reduce tax evasion and legal avoidance would help. About 20 percent of US reportable income goes unreported, and many corporations minimize their taxes through complicated tax havens. If a crackdown on tax evasion occurred, after-tax profits would fall – and they were only $1.8 trillion in 2019. Already US and EU central banks have invested trillions in this crisis. Given the extra spending of more than $2 trillion, it appears that not only the wealthiest or corporations would have to contribute. For a temporary emergency, the claim that “deficits do not matter” is legitimate. Yet it is less clear that such a view is sustainable – or that spending can be easily cut once the emergency ends. Ultimately, desirable programs, such pre-kindergarten childcare, must compete with infrastructure repair or a green new deal. Governments must determine what level of taxation and government spending will prove acceptable.

There are many other angles. Health care in poorer countries, where hospitals and medical personnel are already stretched thin, could suffer. Low-cost medicines and vaccines may help, if intellectual property issues are worked out, as they were for HIV drugs. If the elderly die in large numbers, that could reduce the demand for migration to help with elderly care. Blaming foreigners for diseases could boost isolationist and nativist movements. The world is making many choices on immediate problems, but may create new challenges.

David Dapice is the economist of the Vietnam and Myanmar Program at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.