Economic Nationalism Rises in Indonesia

Economic Nationalism Rises in Indonesia

JAKARTA -- Singapore-based DBS Holdings Group announced in April it would pay US$7.2 billion to take over Bank Danamon, Indonesia’s sixth-biggest bank. Only three weeks later Bank Indonesia, the country’s central bank, announced that it would issue new rules limiting international ownership in local banks, putting the Danamon takeover on hold – until after the new ownership rules are promulgated and Singapore agrees to reciprocal arrangements for lenders operating in the two countries. No one is certain when that will be. That has dismayed at least three other foreign banks that had plans to acquire Indonesian institutions.

The rules are the latest manifestations of Indonesia’s troubling increasing economic nationalism and antipathy towards multinational investment. Despite the country’s enviable economic growth over the past decade, the government is considering a raft of measures to lock in its position with state enterprise-driven resource monopolies that could well end up hurting its growth and global position.

That has troubled the international rating agency Standard & Poor’s, which in late April declined to upgrade Indonesia’s sovereign debt from BB+, one step below investment grade, because the country’s plan to lure investment is at risk from “policy slippages.”

What are these policy slippages? In late April for instance, the government announced that a government-linked company, the Indonesian Ports Corporation, would take on the monumental job of building a US$1.9 billion new port at Tanjung Priok in North Jakarta. It’s arguably the biggest infrastructure project in Indonesia’s history and one of the biggest port projects in the world. The government had previously cancelled international tenders for the terminal, outraging private-public consortia that had devoted considerable funds into preparing the bids only to see them thrown out.

These protectionist predilections, built on the country’s steady 6 percent-plus growth and its stellar performance during the global credit crunch that struck in 2007, have emboldened the government and particularly Kadin, the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce, to continue to tighten against international entry.

Indonesia is largely alone in a region that has seen globalization and FDI as the path to prosperity. Jakarta, however, is aware that it presides over Southeast Asia’s biggest economy. Domestic consumption insulated it from the global financial crisis. It’s also the world's largest exporter of palm oil and natural gas and the second-largest exporter of coal. Foreign investors continue to beat a wary path in because of their desire to tap the US$1.1trillion domestic economy and its export potential.

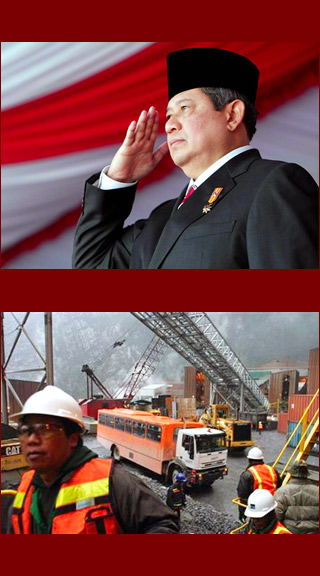

New trading curbs will apply to exports of 14 metals, including iron ore, manganese, gold, silver and copper. Exports will be limited to refined exports only, forcing more value-added production within Indonesia. Mining exploration was brought to a halt, dismaying international investors, when President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono signed a new law into effect in early March forcing foreign investors holding mining and special mining business permits to begin divesting their operations to Indonesian entities within a five-year period.

The divestment must begin during the sixth year of mining production. Under the existing regulations, by the sixth year Indonesian investors must own at least 20 percent, which must be increased to 30 percent in the seventh year, 37 percent in the eighth, 44 percent in the ninth and 51 percent at the end.

In addition, in April the government said it plans to impose a 25 percent export tax on coal and base metals this year, jumping to 50 percent in 2013 as it looks to looks to boost domestic investment and take a bigger slice of mining profits.

The country’s ambition to own operations could ultimately drive companies like the US-based mining giant Freeport McMoRan, which operates the world’s biggest copper and gold mine in the Sudirman Mountain Range in Papua, out of ownership altogether, before hiring them back as fee-based contractors.

Freeport currently operates under a 30-year contract of work that allows the company to own 90.64 percent of the mine, the government of Indonesia owning the remaining 9.36 percent. The parent company, believing it has an ironclad contract, has previously said that any changes to the contract of work would require mutual agreement between Freeport McMoRan and the government of Indonesia.

After the new divestment rules were announced in February, Freeport said it would be unaffected by them. However, sources in Kadin say that if they have their way there will be no more profit-sharing and no more long-term mineral rights. Although Freeport has expressed confidence in the current agreement, it has reason to be concerned.

Kadin is said to have a scheme to change the resource code in the constitution so that raw material does not belong to "the people," but instead belongs to state-owned enterprises such as the national energy company Pertamina. The chamber officials suggest that because of the article 33 clause in the constitution and the way that Suharto allowed foreign exploitation of resources, foreign companies are able to claim billions in assets on the basis of the ore or gas they can extract – using that to raise money from investors as apparent "owners" of Indonesia's resources.

Kadin wants Indonesia to "own" the resources and just have service contracts with foreign companies. In so doing, chamber officials assume the state-owned enterprises could raise hundreds of billions in IPO money. Now that Indonesia is rich and realizing its potential, they say, it may be time to complete Sukarno's 1958 revolution, kick out the foreigners, take away their concessions – and turn it all over to Pertamina.

The government appears aware that the protectionist measures against the extractive industry sector will have a deleterious effect, especially in exploration, where most of the high-end activity is carried out by high-tech multinationals with the ability to go where domestics don’t know where to look. Exploration has come to a virtual stop because of the tightened investment rules.

But the government and Kadin assume that eventually they will develop the ability to handle the fallout and that in any case, Indonesia gets a bigger share of a smaller pie – and it’s their pie. These protectionist measures extend beyond minerals. Last October, in an effort to boost the country’s stagnant palm-oil refining capacity, the government introduced a new export tax structure with wider differences between crude and refined palm oil, enabling the country, the world’s biggest palm-oil producer, to sell cheaper refined products and gain market share against Malaysia, which has been looking for countermeasures and so far hasn’t found one.

In the meantime, according to the Trade Knowledge Network of Southeast Asia, Indonesia has been using a number of stratagems through non-tariff measures including expanding quarantine requirements for various import products and using the Indonesian National Standard instead of international standards for various imports. According to the Industry Ministry, there are 86 obligatory Indonesian National Standards, SNIs, and 6,000 non-obligatory SNI standards that must be met although the World Trade Organization must approve the list. Indonesia has been a WTO member since 1995.

According to the Indonesian Trade Security Committee, KPPI, Indonesia was ranked third after India and Turkey on a list of countries that applied protectionist trade barriers, based on WTO data in 2010. Possibly out of retaliation, Indonesian products face antidumping and safeguarding measures implemented by more than 12 countries, according to the Trade Ministry. It’s unclear what the next moves will be. One source describes the tightening process as “seeping.” But it will continue.

John Berthelsen is the editor of the Asia Sentinel, an online journal covering news, comment and analysis of politics, business, economics and other affairs across Asia.