Emptying the Oceans

Emptying the Oceans

SINGAPORE - The world's fisheries are in a deepening crisis, as consumer demand rises and growing numbers of mainly European and Asian fishing vessels, frequently supported by government subsidies and equipped with technology that enables them to find and catch fish at ever greater depths, roam the oceans.

United Nations studies have shown that 75 percent of the the fisheries are being harvested to their full capacity or over-exploited and need immediate action to freeze or reduce fishing to ensure future supplies.

Meanwhile, consumption of fish worldwide has soared. The global sea fishing catch reported by governments and compiled by the FAO, the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome, increased from 19 million tons in 1950 to about 80 million tons in the mid-1980's. But since then, the total reported catch has oscillated between 78 million tons and 86 million tons annually.

Many scientists believe that this plateau is a sign that the point of maximum harvest has been reached and may, indeed, mask a dangerous decline in breeding stocks as more species and younger fish are taken from the sea.

"Fish stocks in many parts of the world are suffering as too many, often heavily subsidized, vessels chase a dwindling number of fish," said Klaus Toepfer, Executive Director of the UN Environment Program, UNEP.

In what many scientists and environmental activists regard as a long overdue, but now probably inadequate, response to the crisis, officials of 189 nations attending the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg agreed on 27 August on a draft agreement to allow overfished waters to recover by 2015.

Under the accord, governments will aim to rebuild fish stocks to a sustainable level by that date at the latest. This could require temporary fishing bans. Governments will also consider setting aside permanent non-fishing zones to preserve breeding grounds.

But the agreement is not legally binding and there are serious doubts that it will be effectively enforced. "Overcapacity means that you have too many ships on the sea chasing too few fish and when this happens people are bound to bend the rules and harvest illegally," said Gordon Shepard, director of international policy for WWF International, the World Wide Fund for Nature. He estimated that the number of commercial fishing boats in operation was 2.5 times the maximum that could be allowed for sustainable fishing.

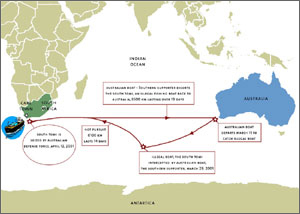

Consider this case: The South Tomi, a rusty ocean-going trawler, had hauled in 90 metric tons of Patagonian toothfish worth around 800,000 US dollars when it was spotted fishing illegally for the endangered species in the remote and stormy waters of the Southern Ocean, between Antartica and New Zealand, Australia and South Africa. The South Tomi was found fishing off two remote islands owned by Australia. When challenged by an unarmed Australian fisheries inspection vessel, the trawler fled westwards towards South Africa, shadowed by the Australian ship.

The pursuit, which covered over 6,100 kilometers and lasted 14 days, ended on 12 April, 2001, when Australian soldiers, flown to South Africa by the Australian government, boarded the South Tomi several hundred kilometers off Cape Town with the aid of the South African navy. The soldiers took control of the trawler and made the 44-man crew sail back to Perth, in western Australia, some 8,500 kilometers away, for prosecution in court.

The toothfish - sold as Mero in Japan and Korea, and Chilean Sea Bass in North America and Europe - is a popular restaurant dish in many countries. Prized for its white, flakey meat, it became a darling of the seafood industry about a decade ago, after marketers changed its name from the less-than succulent sounding Patagonian toothfish.

But as consumers and chefs in the United States learn of the scale of unregulated fishing and the possible extinction of the toothfish within five years, they are starting to boycott Chilean Sea Bass. More than 90 restaurants in Los Angeles and Orange counties pledged last May to remove the fish from their menus, following similar promises by chefs in Northern California, Chicago and Houston. The "Take a Pass on Chilean Sea Bass" campaign is expected to spread to New York, Philadelphia and Washington D.C.

Conservationists say that 80 percent of the annual toothfish catch is illegal. The Monterey Bay Aquarium, which has the fish on its "avoid" list, estimates that the illegal catch of the Patagonian toothfish may be ten times the legal haul by licensed boats.

Australia estimates that 13,750 tons of toothfish valued at about 100 million US dollars wholesale were poached from its Antarctic or sub-Antarctic economic zones in 2001. Licensed fishers there took about 1,650 tons, a quota based on scientific advice on what the stocks can sustain.

The U.S. Department of Commerce and the Customs Service, responding to intelligence reports from the Australian government, recently seized four illicit shipments of Chilean sea bass totalling more than 100 tons in Boston; Newark, New Jersey; Los Angeles; and New Bedford, Massachusetts. The cargoes were valued at about 800,000 US dollars and about four times as much at retail and restaurant levels.

In early September, a French court confiscated one of the most notorious pirate trawlers that chase toothfish in the Southern Ocean. It also imposed heavy fines on the Spanish officers of the Eternal, which was seized by the French navy after an Australian fisheries patrol vessel spotted it fishing illegally near French-owned Kerguelen Island.

The trawler had been intercepted in French waters in the area in September 1999, when it flew the Panamanian flag. It subsequently changed its country of registry to Uruguay and then the Netherlands Antilles. Australia has captured at least three pirate trawlers in its Antarctic economic zone this year. French patrols have seized 15 such vessels in French waters in the area in the last three years.

United Nations officials, environmentalists and scientists say that the epic chase of the South Tomi and the more recent seizure of the Eternal illustrates an alarming trend: as fisheries closer to the major centers of population in Asia, Europe and America reach the point of collapse because of excessive exploitation, trawlers and factory ships are moving to remote regions that are even more difficult to police so that they can continue to overfish.

Largescale fishing for the Patagonian toothfish began in the southwest Atlantic off the coast of Argentina and the Falkland Islands in 1994 and has since spread into the Southern Ocean as the catches off Argentina and the Falklands dwindled.

Last March, the Australian government sent two naval ships some 4,000 kilometers out into the Southern Ocean to apprehend two Russian vessels poaching 200 metric tons of Patagonian toothfish worth 1.25 million US dollars near the same remote Australian-owned islands where the South Tomi was caught.

"As the shallow-water fisheries everwhere have collapsed, there has been a worldwide scramble to exploit the resources of the deep ocean, with devastating consequences," said Callum Roberts, an ocean ecologist at Harvard University.

"Forty per cent of the world's trawling grounds are now in waters deeper than the continental shelves," he told the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston in February. "And some new technology is so efficient that these deep-sea trawlers are not just harvesting fish, they are literally mining them."

Deep-ocean trawlers can now net fish at depths of more than 1.6 kilometers and pull in as much as 60 tonnes of fish in 20 minutes. "The boats of today are larger, faster, stronger and can fish in conditions that would have been highly dangerous a hundred years ago," said Yvonne Sadovy, a fisheries expert at the University of Hong Kong. Increased demand for fish, she added, makes it profitable to pursue them to “the farthest corners of the world."

Scientists say that the scramble to exploit deep water fish may be a more serious threat to stocks than the overfishing of waters close to shore. Some near-shore fisheries, like those of the Alaska salmon rebound quickly. But deep-water species grow and recover more slowly.

For example, the Patagonian toothfish does not start to reproduce until it is about 10 years old and can live for over 40 years. The orange roughy, also known as deep-sea perch, is another fish that has been popular in seafood restaurants. It does not begin to breed until it is 20 years old and may live to the age of 150 years.

As a result of a decade of overfishing in the orange roughy's spawning grounds off Australia and New Zealand, the catch plummeted by as much as 70 percent. Five years of intensive French fishing in the North Atlantic has reduced the catch of roughy there by 75 percent.

Overfishing in the Pacific and Indian oceans is following the same trend as the Atlantic, where many once-thriving fisheries like the cod grounds off eastern Canada have collapsed. Many of Europe's most popular fish, including haddock and hake, are at dangerously low levels.

The overfishing in Europe has forced governments to impose quotas, cuts in fishing fleets and other restrictions in the hope that fish will breed and stocks grow again to a size that can be harvested on a sustainable basis. The European Commission announced plans in May for cuts in national fishing fleets of up to 60 per cent, despite tough opposition from member nations. The plan calls for the end of subsidies to boost fishing capacity and a tighter enforcement of fishing limits.

The measures would affect the entire European Union fleet of 100,000 vessels that fish in E.U. waters and off the coasts of Africa and North America. "Either we make bold reforms now, or we watch the demise of our fisheries sector," said E.U. Fisheries Commissioner Franz Fischler. "The desperate race for fish has to stop."

But environmental activists say that banning some ocean-going fishing vessels from national waters in the interests of conservation frequently results in those same vessels registering abroad and going elsewhere. The South Tomi, for example, was Spanish-owned but registered in Togo, West Africa, Australian officials said.

The emergence of many Asian countries in the top ranks of distant-water fishing nations has compounded the difficulties of regulating and policing remote fisheries. It has also increased the global competition for fish which is an important part of people's diet in Japan and many other Asian countries. Fish is not only a key source of protein in Asia; fishmeal is used to produce livestock and poultry.

For example, dozens of ocean-going trawlers and factory vessels from Japan, China and South Korea, as well as the EU, now crowd the fishing grounds off West Africa. A report compiled for UNEP found that overfishing in Mauretainian waters caused by the failure of some of the foreign boats to comply with rules and lack of enforcement had led to a dramatic fall in catches and mass unemployment among local fishermen.

The FAO estimates that developing countries now account for 50 percent or more of world fish trade, up from 32 percent in 1970. The trade is worth over 50 billion U.S. dollars a year. Nearly all the developing countries that have become fishing powers are Asian.

Yet when a new UN treaty on marine fish management came into force last December 11, 15 of the top 20 fishing nations had failed to ratify it and most of them were from Asia. Officially known as the 1995 UN Agreement on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, it is the most far-reaching treaty ever negotiated to promote the conservation of marine fish, including commercially valuable tuna and swordfish.

The treaty applies to fisheries both within and beyond countries' exclusive economic zones that extend 200 nautical miles from their land territory. It sets new international standards for fisheries management, including unprecedented monitoring and enforcement regulations.

The United States, Russia, Canada, Iceland and Norway have ratified the treaty. But other top fishing nations have not. They include China, Denmark, Peru, Japan, Chile, Indonesia, India, Thailand, South Korea, the Philippines, Malaysia, Mexico, Vietnam, Argentina and Spain.

"The world's 20 top fishing nations account for nearly 80 percent of the world catch," said Simon Cripps, director of the endangered seas program of WWF International. "While their support is not needed for the UN Fish Stocks Agreement to enter into force, their compliance is essential for the treaty to be effective."

There are some 34 regional fishery bodies operating worldwide, including nine established under the FAO and 25 under international agreements between three or more contracting parties. But even so, only about half the world's oceans and seas are regulated in some way and many of the regional arrangements are difficult to enforce. Some regional fishery bodies even have problems agreeing on the rules.

Australia recently withdrew a proposal to extend trade controls on the Patagonian toothfish by having the species listed on the relevant appendix of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, when the 160 signatories to the treaty met in Santiago, Chile. Australia did so after it became clear that some countries, among them Chile and Japan, opposed the move. Instead, Australian officials said that they would continue to work with the other 23 members of CCAMLR, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, to combat pirate harvesting of the toothfish, whose population in the Southern Ocean around Antartica is reportedly shrinking fast and may be at risk of becoming commercially extinct by 2007 because of illegal overfishing. But working soley through the regional body to regulate commercial fishing is regarded as inadequate by many scientists. For example, some members of the regional group refused this year to support an Australian proposal to establish a centralised vessel monitoring system to make it easier to track and apprehend pirate fishing boats.

International talks to conserve the breeding stock of an endangered tuna species in the Pacific broke down in October 2001 when Japan, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea meeting in the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna were unable to agree on new catch quotas.

Environmentalists blamed Japan for insisting on a quota increase. "Japan is more interested in increased catches for its industry than in the recovery of the species," said Vanessa Atkinson, an oceans campaigner for Greenpeace in Sydney.

Catriona Glazebrook, executive director of Pacific Environment, a non-government organization based in Oakland, California, said that one of the latest fisheries boom areas, the North Pacific, is now showing indirect but telltale evidence of overfishing - an increasing number of severely underweight whales, especially endangered Western Pacific gray whales, that are having difficulty finding enough smaller fish to eat.

"This is a grim development," she said. "These graceful creatures are near the top of the food chain and are thus indicators of problems that are widespread. What they're telling us is that their eco-system is starving to death."

Ms. Glazebrook said that the North Pacific was one of the most world's most productive international fishing grounds and many saw it as a place to make a big short-term profit.

"Factory fishing trawlers come from all over the world and drag huge nets behind them, some as long as the Empire State Building is tall," she said. "They are literally strip mining the ocean floor of sealife."

Scientists, environmental activists and concerned officials all say that if a global fishing catastrophe is to be averted governments must cooperate more effectively to regulate fisheries and enforce conservation controls. Fishing fleet subsidies must also be ended and consumer boycotts of pirated and endangered fish species intensified by including big buyers, among them fish importers and supermarket chains.

Michael Richardson is Senior Asia-Pacific Correspondent of the International Herald Tribune.