Ending Isolation – Part II

Ending Isolation – Part II

SAN FRANCISCO: Despite growing buzz about changes in Cuba, the country found itself uninvited once again to the Summit of the Americas in Cartagena this month. The move is grounded in a resolution that only “democratic” countries should be invited, with the United States and Canada insisting that Cuba has not earned a seat at the table. These countries hold – correctly – that the main responsibility for Cuba joining the world still lies with Havana and its policies. Cuba, timidly launched on a path of reform, will one day join the table again, but whether isolationism is the right path to encourage change is debatable.

Cuba once featured prominently on the international map. Through the 1950s, Cuba was one of Latin America’s strongest trade powers, benefiting from its proximity with the United States.

All this changed with the coup that brought Fidel Castro to power in 1959 and started the Cuban Revolution. Fidel expropriated and nationalized US properties on the island, establishing a communist state and aligning the country with the Soviet Union. Soon afterward, International Monetary Fund and World Bank memberships were rescinded; the US embargo cut off the island from its trade and cultural neighbor to the north. While Cuba remained throughout the decades an active participant in the United Nations, its participation in the Organization of American States, OAS, was suspended in 1962, though it remained a member with the suspension lifted in 2009.

As the revolution was largely predicated on a break from influences of the north and West broadly defined, the island became a lonely enclave in an otherwise non-communist world. Soon after the US embargo took effect in 1962, Fidel used it for explaining away the country’s ills and closing ranks against a common Goliath.

For decades, Cuba turned to the Eastern bloc for international positioning. The USSR dominated Cuba’s trade, largely through subsidies – while the relationship was not without difficulties, it provided the island with an anchor in the world order.

With the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 and withdrawal of Soviet subsidies and decline in trade, Cuba saw its economy contract by 35 percent. The US embargo negated the possibility of re-engagement after the fall of the Eastern bloc. Attempts to open foreign investment and trade came and went depending on political winds.

In the first decade of the millennium, Cuba saw investment by the likes of Canada and Spain, but remained effectively without major allies. The European Union, in response to Cuba’s dismal human rights record, suspended cooperation and assistance to Cuba from 2003 to 2008. While on paper Cuba provided foreign-investment legislation, the lack of rule of law kept many investors at bay – not without reason. Over the years, investors witnessed an ebb and flow of openness and closure, dotted with restrictions on repatriation of proceeds and strangling limitations on foreign enterprises.

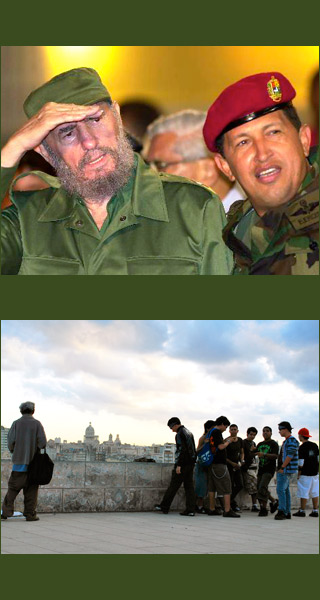

Not until the 1999 ascendancy of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela did Cuba found another patron. Chávez, a socialist and self-professed admirer of Fidel Castro, underwrote the survival of the Cuban economy by trading subsidized oil for Cuban services, most notably doctors, teachers and security advisors. The extension of support by the likes of Brazil’s Lula and Bolivia’s Morales has not come close to the economic impact of the Caracas-Havana lifeline.

The Venezuelan leader is facing a tough re-election and struggling with cancer. While there’s disagreement on how post-Chávez support might be withdrawn from Cuba, consensus is that it will decrease and Cuba could find itself orphaned once again.

Short of seeking another benefactor, Cuba must look to the international community for support. Emerging economic superpowers are one reference point: China has extended commercial credit for Cuba’s imports, and Brazil, most notably, invested in the overhaul of the port at Muriel. President Dilma Roussef’s visit to Cuba earlier this year heralds interest. However, both Brazil and China are possible commercial partners and attach conditions to engagement. They also have their own agendas. China appreciates a foothold near the United States. Brazil vies for regional diplomatic primacy as new superpower, while Venezuela seeks to extend its area of influence, however anachronistically, as icon of the Latin American left.

To emerge from its doldrums, Cuba must offer itself as more than a pawn on the Western chessboard. Cuba’s recovery requires a fundamental overhaul of its dysfunctional centrally planned economy and Orwellian state.

Cuba must find new ways of engaging with the world – and that requires fundamental changes how the country is run. No country longing for an international presence can afford to have a fictitious dual currency regime and a state apparatus that employs 80 percent of the work force.

Aware of the challenges, President Raul Castro pushed through a series of detailed economic reforms in 2011 – more than 300 in all – that, if properly implemented, will lead to a more open economy, including self-employment, a smaller state sector, the legalization of real estate transactions. The implementation is slow and painful – involving the firing of hundreds of thousands of people from the state payroll, establishment of an income tax system, and adaptation to self-employment within a byzantine system of state-obsessed regulations. The leadership is, however, adamant that economic reform does not forebode political changes: In fact, the economic reforms are a means of ensuring the survival through change of Cuba’s brand of socialism. Notably, Castro and the leadership have refrained from embracing any outside model for reforms – neither China nor Vietnam – insisting rather on Cuba’s exceptionalism.

There’s no question that a stronger private sector and more openness toward the rest of the world would wield political changes in Cuba – giving a plausible excuse to the United States to progressively ease the 50-year embargo and allowing a gradual rapprochement with the international financial institutions that Cuba abandoned in the 1960s.

Miami Cubans – long the main advocates of isolating Cuba – are now much less hardline than their parents were, and would welcome a gradual reengagement. The stranglehold of the old guard Miami lobby on Washington’s Cuba stance should come to an end.

There’s been a spate of calls for Cuba to start a process of engagement with the World Bank and the IMF, most notably by Richard Feinberg in a detailed Brookings Institution paper. Drastically undercapitalized, Cuba cannot access capital on the open markets due to its dismal credit history. Aside from US opposition, it makes no sense for the international financial institutions to exclude Cuba, given their universalist mandate – their membership covers virtually every country on earth, with the exception of Cuba, North Korea and some micro-states – and history of engagement with needy economies regardless of political proclivities, from Vietnam to Nicaragua.

Cuba has given weak signals that it welcomes such help. This is likely to be a slow process, but one that institutions should undertake – even in the face of less persuasive opposition by the United States.

While there have been signs that engagement might accomplish more than hardline exclusionism, the US approach still prevails. The Summit of the Americas would have been a prime forum for recognizing Cuba’s attempts at openness and pushing it ahead with carrots, not sticks. President Obama indicated his country’s openness to having Cuba take part in future summits if the country advances toward democracy. Pressure toward inclusion from the other OAS countries is mounting, and it will be none too soon when Cuba will be allowed to re-engage.

Andrea Armeni is foreign correspondent (Americas) for Emerging Markets Magazine.