To Eradicate Measles, Destroy Vaccine Myths

To Eradicate Measles, Destroy Vaccine Myths

NEW HAVEN: The current US outbreak of measles underscores yet again that in a globalized world infectious diseases cannot be eliminated unless eradicated everywhere, as was the case with smallpox in 1977. The measles virus, like smallpox, is only found in humans, not animals. Therefore, with the highly effective inexpensive vaccine that exists, measles could be eradicated. Thanks to current global efforts, an estimated 15.6 million deaths were prevented from 2000 to 2013. The World Health Organization regions have goals to eliminate this preventable killer disease by 2020.

However, the world may not reach this goal.

While people do not shudder upon hearing the word “measles” as they do with “smallpox” or “Ebola,” this does little to lessen the heartache of the thousands of parents who lose their children to measles or see their children develop pneumonia, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) or even go blind as a result of the disease. WHO reported 145,700 measles deaths globally in 2013, about 400 deaths every day, mostly among children under the age of five. Worldwide, 20 million people were infected with measles that same year. Thanks to the measles vaccine, an estimated 15.6 million deaths were prevented from 2000 to 2013.

The current US outbreak highlights challenges to eliminating this preventable disease. The outbreak started in December at California’s Disneyland amusement park, which attracts visitors from around the world. It is suspected that a person had been infected in another country and visited the park. The highly contagious disease spread to individuals in 17 states with more than 120 people falling ill, reports the Centers for Disease Control.

This is not the first outbreak since measles was eliminated in the US in 2000; localized outbreaks still occur. For instance, 12 children in San Diego, California became ill in 2008 with measles after a 7-year-old boy contracted the disease during a vacation in Switzerland. Unvaccinated infants are most vulnerable. Of the affected children, three were too young to receive the first dose of the vaccine, normally given at 12 months of age. The other nine children were not vaccinated.

As long as measles is prevalent in the rest of the world, unvaccinated children in any country are at risk – even in those countries where the disease supposedly has been eliminated.

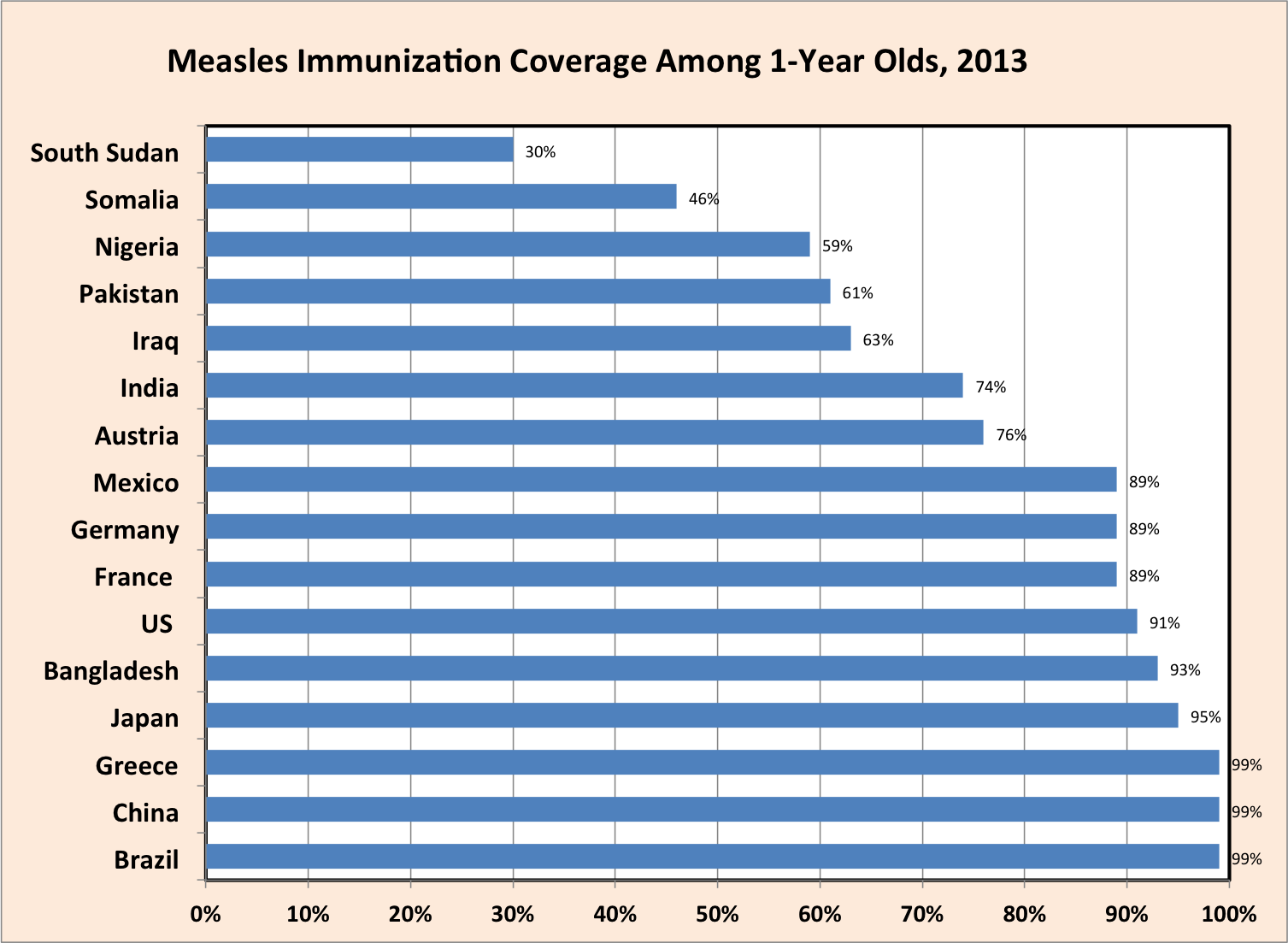

In countries with strong health infrastructures, parents’ decisions not to vaccinate hinder medicine’s goal of eradicating measles. The measles immunization coverage in 2013 by country collected by the WHO indicates that the variability in vaccination rates is not solely based on wealth of a nation. A 2014 article by Norimitsu Kuwabara and Michael DL Ching described contributing factors for lower than expected incidence rates of vaccine preventable diseases in Japan. Misconceptions about side effects and vaccine efficacy are another factor.

To eradicate measles, health officials must not only help make vaccines available to countries with weak health infrastructures, but also change the thinking of parents in the wealthy developed countries. Science and health education help counter unfounded fears.

Humans and other vertebrates have an adaptive immune system in addition to other forms of immunity present in all organisms. This adaptive system, when it encounters the measles virus, produces proteins called antibodies that bind to the virus, blocking it from infecting cells. It also produces killer T-cells that eliminate infected cells. The killer cell can distinguish between healthy cells and cells harboring a virus inside. Unfortunately, it takes five to seven days to develop an active adaptive response against a virus. During this period, the measles virus multiplies and spreads. In a previously vaccinated individual, the antibodies to measles are already present when a person is infected with the virus. In addition, special cells called memory cells are present. These cells are primed to respond quickly and efficiently so that more antibodies are made and the killer cells are activated in about a day. Therefore if someone has had the vaccine their adaptive immune system can respond immediately and stop measles before it causes disease.

Arguments against vaccination include worries about toxicity and children developing “better immunity” with a natural infection. While a measles infection leads to immunity, it also carries serious health risks, especially in infants. Contracting measles to develop immunity does not stand to reason when a vaccine is available. The vaccine consists of a weakened or attenuated form of the Edmonstron-Enders strain of the virus that is highly effective and not toxic. The vaccine exposes people to a form of the virus that is immunogenic, but not pathogenic. That is, the vaccinated individual develops immunity but not the disease. Once immunity against the virus is formed, it’s lifelong. The virus is relatively stable genetically unlike the influenza virus.

Myths and fears regarding vaccination are not new. When Edward Jenner first published his finding in 1798 that the immunization of individuals with cowpox virus would produce mild disease and render full protection from smallpox, rumors emerged that people would develop horns like cows from the inoculation. People at the time did not know about viruses. Today, we know that the two viruses causing smallpox and cowpox are genetically similar so that immune cells against cowpox can also kill cells infected by smallpox and antibodies can block both viruses.

During the late 20th century another myth emerged – that the measles vaccine might cause a child to develop autism. The incidence of autism had increased in countries such as the United States, but the reason is unknown. In the 1960s, many blamed mothers, suggesting a distant attitude hampered their child’s development. A single paper was published by a leading journal in 1998, suggesting a link between autism and the vaccine. The paper was since discredited and retracted, with the lead author losing his license to practice medicine. Follow-up studies conclusively demonstrated no link. Anecdotal stories by some parents struggling to understand why their child had autism perpetuated the myth.

It is imperative that as many people as possible be vaccinated to protect vulnerable individuals such as infants or people with a weakened immune system who cannot be vaccinated. People with immune deficiencies or receiving chemotherapy for cancer are vulnerable. The vaccination of large numbers of people with the recommended two doses of the vaccine leads to the development of what has been termed “herd immunity.” With strong herd immunity, the vast majority of people are vaccinated so that vulnerable individuals are much less likely to be exposed. This dramatically reduces their risk of infection and harm from the disease.

We have the means to succeed.

In the mid-1970s, routine measles vaccination began in many countries. In 1980, only 16 percent of the children worldwide were vaccinated, and measles caused 2.5 million deaths. In contrast, 72 percent of children were vaccinated by the year2000 and the number of deaths dropped by over 70 percent since 1980 to 750,000 deaths. In addition, vitamin A supplements, known to contribute to maintaining a healthy immune system, reduced the severity of measles in children with vitamin A deficiency. Worldwide efforts are paying off.

Measles can be eradicated from the world if enough people are vaccinated worldwide through a global effort. Then, as happened with smallpox, no one will need the measles vaccine, and the world will be better off.

Paula Kavathas is professor of laboratory medicine and of immunobiology at Yale University School of Medicine and chair of the Yale Women’s Faculty Forum.